Documentarian Don Hahn spent hours poring over the home’s history and significance for the creation of his film, The Gamble House. Here he discusses his fascination with the residence and story of its creation.

What made you want to tell the story of The Gamble House?

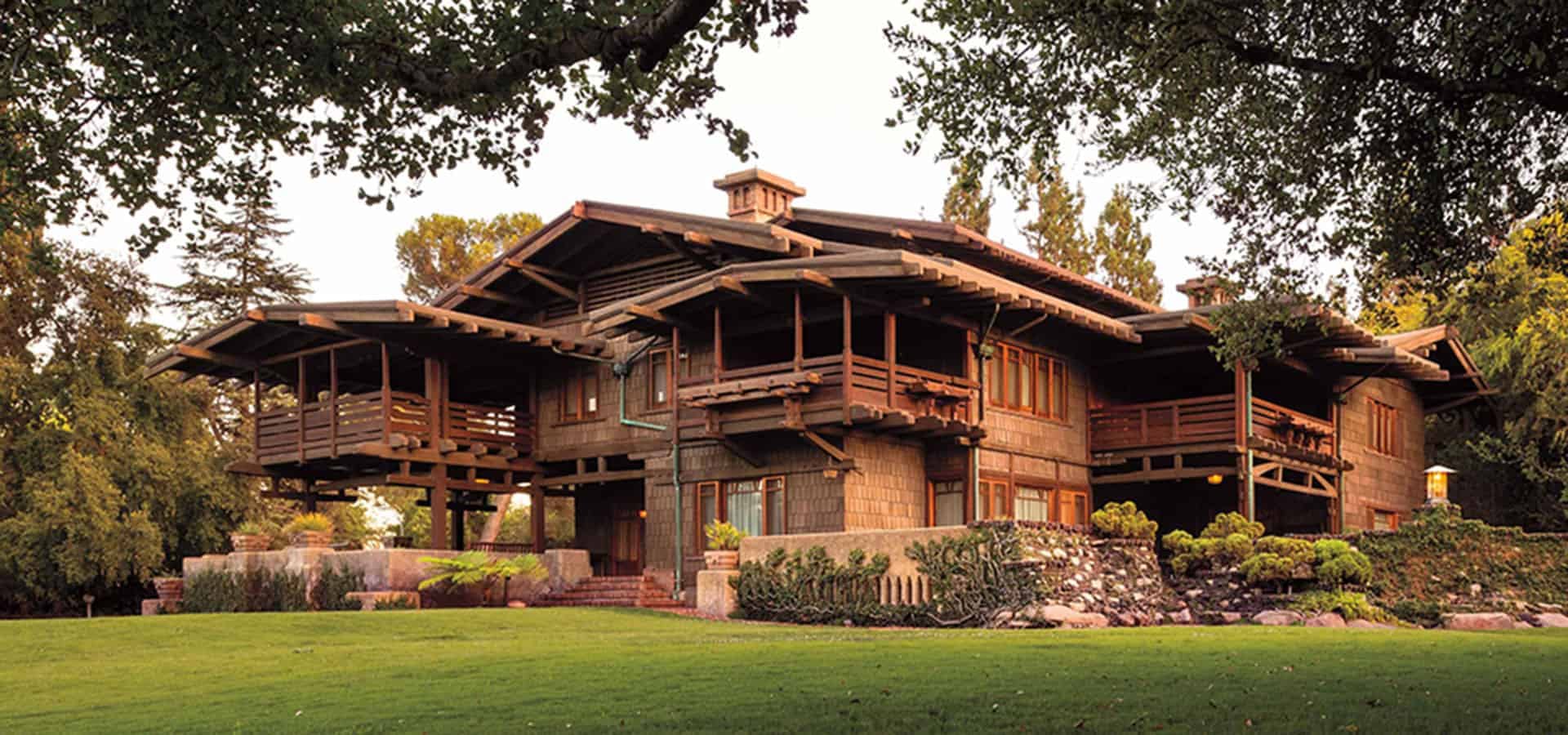

Don Hahn: I love architecture but knew so little about architecture history. I suppose I knew what the average guy on the street knows… about Frank Lloyd Wright, and a little about some of the celebrity names in Western architecture like Lautner, Schindler and Nuetra. But all of those pioneers of modernist architecture in California repeatedly referred back to an architecture firm from Pasadena that was in business for a few years in the late 19th and early 20th Century: Greene and Greene. I knew them in association with the Gamble House, and I loved that the Gamble House was also a Hollywood icon as Doc Brown’s House in Back to the Future, so I started reading. What unfolded was a story that had only been told in a few wonderful books on the firm, but never in a film. I wasn’t interested in the bricks and mortar of the house, or the restoration of the house, which had been done so exquisitely 10 years ago. I was only interested in the people: Charles and Henry Greene, and their clients David and Mary Gamble. Who were they and why did they build such an eccentric and modern home on the edge of the Arroyo Seco in Pasadena? The story that unfolded was unbelievable and encouraged me even more to tell their story.

Do you remember the very first time you saw the house in person?

DH: I had toured the Gamble House many years ago, and loved the look and feel of it all, but had no idea what the story of the house was. Now I see it as such an obvious homage to Japanese building techniques and Asian influences, but when I first stepped inside, I saw it only as an arts and crafts house. That was, after all, the most common moniker attached to the place: The Ultimate Bungalow. Now I see it not as a bungalow at all, and not as an arts and crafts house in the British or East Coast sense of the arts and crafts tradition. I see it as the first modern house that took the aesthetic of the arts and crafts movement and applied it to California, and the lifestyle of the west.

While making this film, what things surprised you the most?

DH: The most surprising part of the story of the Gamble House is that the architects really didn’t want to be architects at all. Charles Greene would much rather have been a painter or a poet of a writer of some sort. Eventually he dropped out of his practice and moved to Carmel California where he could practice all of those things, but the few years that he and his brother Henry designed and built houses in Southern California were the touchstone for modernism on the west coast.

You must have spent a lot of time in the house during production, something that most people don’t get to do. Did you imagine what it must have been like living there almost a hundred years ago? If so, what stuck with you?

DH: Most people think that the interior of the house is dim and poorly lit, but I didn’t see it that way at all. Yes, the electrical bulbs were low wattage at the time, but the illumination comes from the California sun that races through the front windows in the morning, the dining room windows at noon, and finally thru the living room and master bedrooms in the evening as the sun sets. The siting of the house takes perfect advantage of the moving sun. It also takes advantage of the prevailing breeze that blows from the Arroyo Seco canyon below the house up thru the windows and vents, so that the house is always bathed in fresh air. The sleeping porches and wide doorways also were the start of indoor/outdoor living that would become so popular in ranch houses nearly 30 years after the Gamble House was built. All of this focus on natural light, fresh air, and the outdoors is only augmented by the materials that the Greene’s selected. The arroyo stone foundations are flared at ground level so the building looks as though it’s growing out of the ground. The use of redwood, cedar and fir all brought the extraordinary materials that were available at the time into close contact with the residents, along with hand made glass patterned in dozens of natural motifs. The whole thing has an effortless, almost inevitable quality to it, as though all the choices were preordained, but when I read the research and the painstaking lengths that the Greene’s pursued when they built this house, it was anything but inevitable.

Why do you feel a film on The Gamble House is important?

DH: California was the perfect place for a new native and modern architecture to grow, and the Gamble’s and Greene’s were the perfect match of client and architect to start that trend. No one else was blending the influences of Europe with influences of the American East, with influences of Japan and Asia. This mash up of styles and inspirations landed perfectly on Westmoreland Place. It was a building well ahead of its Edwardian time, and was the harbinger of the modern movement in architecture that would follow. Architects have long studied the inspirations and plans for the house. I wanted to study the people. That’s what made the film worthwhile.

For you, who are the most vibrant characters in the story of the house?

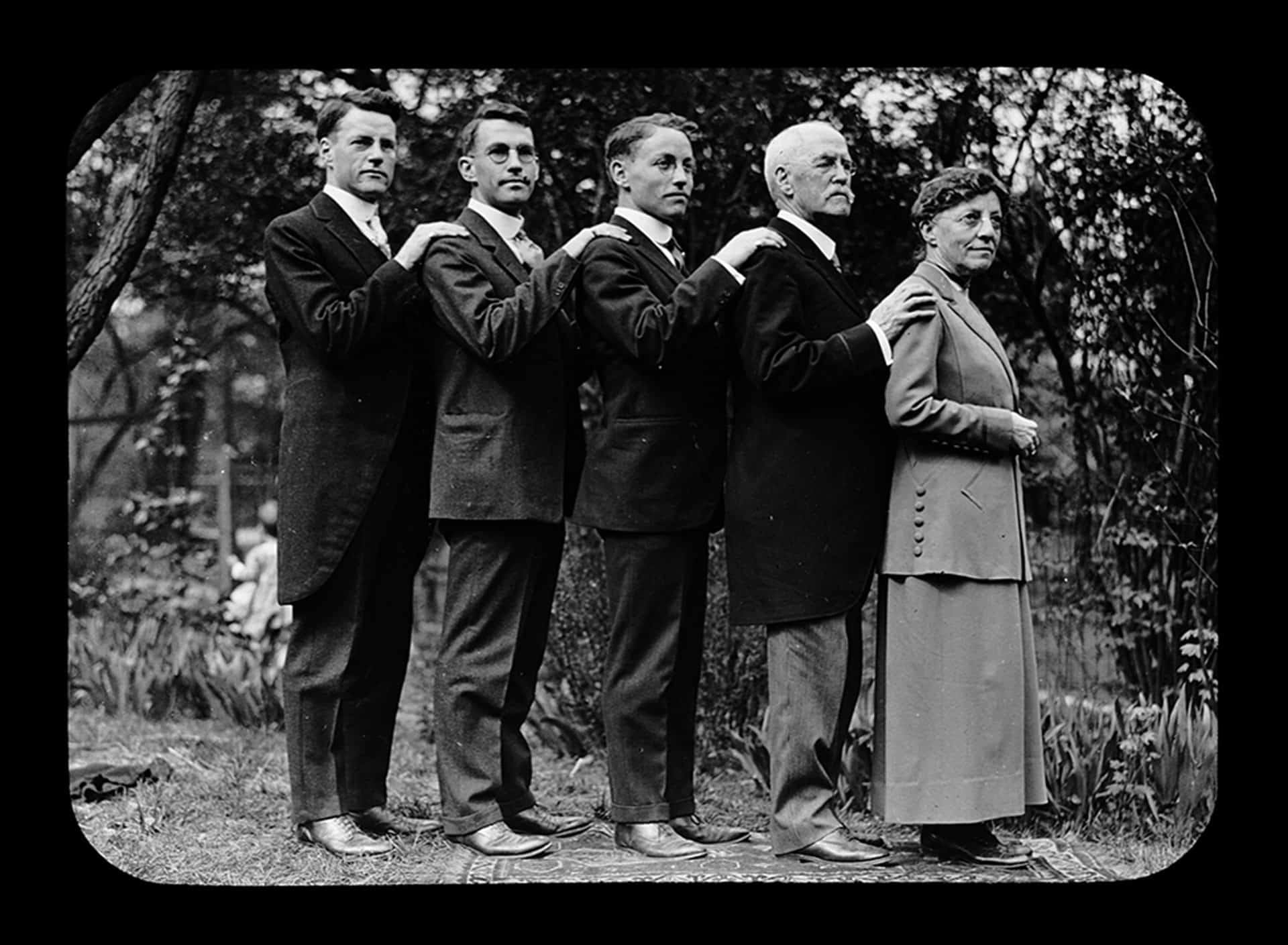

DH: To me the story is all about Charles Greene and his father, Thomas. That’s not to take away anything from Henry Greene, the pragmatic, gifted brother of Charles, but without Thomas Greene, and his unrelenting push to make architects out of his sons in the post Civil War, there would be no Greene and Greene. And without Charles, the gifted, tormented, charming, perfectionist of an artist, there would be no Gamble House. Add to that the fearlessness of Mary Gamble, and her husband David, for commissioning the house and putting up with the cost overruns. And finally the Swedish carpenters Peter and John Hall, the brilliant craftsmen able to execute the Greene’s plans like no other before or since.

For you, what is the house’s best feature?

DH: The best feature of the house is the wood that lines nearly every surface, inside and out. It’s wood that is no longer available; old growth wood from a century ago that adorns the surfaces, and gives the house its warmth and living appeal.

What do you hope this film accomplishes?

DH: We live in a golden age of documentaries, and the tools for a film maker—low light cameras, drones, gyroscopic camera rigs—all allowed us to film the house like never before. I hope the film gives a new understanding of the miracle of good architecture and design, and can enlighten the audience to a couple of brothers who all but fell into obscurity after their career was over, but to whom we owe a tremendous debt. They opened the door for all of us to live in environments that promoted health and wellbeing, and that fostered a partnership between natural materials, light, fresh air, and the benefits of all of that on the human soul. If I can share that vision for a better way to live, as the Greene’s saw it a hundred years ago, then that’s a great accomplishment, and gives reason for this film.

When you think about the other houses that the Greene brothers designed and built, the ones that no longer stand, or the ones that have been stripped of their original furniture and fixtures, how does that make you feel? To you, is that what makes The Gamble House so special, that it retains all the elements as the Greene’s designed and intended them?

DH: Houses, just like the families who inhabit them, are ephemeral and transient. It’s a sad but perfectly natural fact that many of the Greene’s houses have been demolished or remodeled beyond recognition. It’s with that knowledge of the temporary nature of life and our homes that we can look at the Gamble House as a modern miracle. When you walk inside the front door of the house, you are walking into 1908, and a way of life long gone. But in that way of life you can feel and hear the voices of the past, and the wisdom that they brought to the quality of their lives. These were privileged people for sure, but in their generation, they formed the National Park System, and gave women the vote, they went from horses to automobiles, and then to airplanes, and in architecture they went from gingerbread and Victorian clutter to the beauty and the simplicity of something like the Gamble house. The house is simply wood and brick and stone, but it’s the people who made it live. That’s what’s unique about it and that’s the story that I tried to capture in the film.

Want to see the home in person? Visit gamblehouse.org.