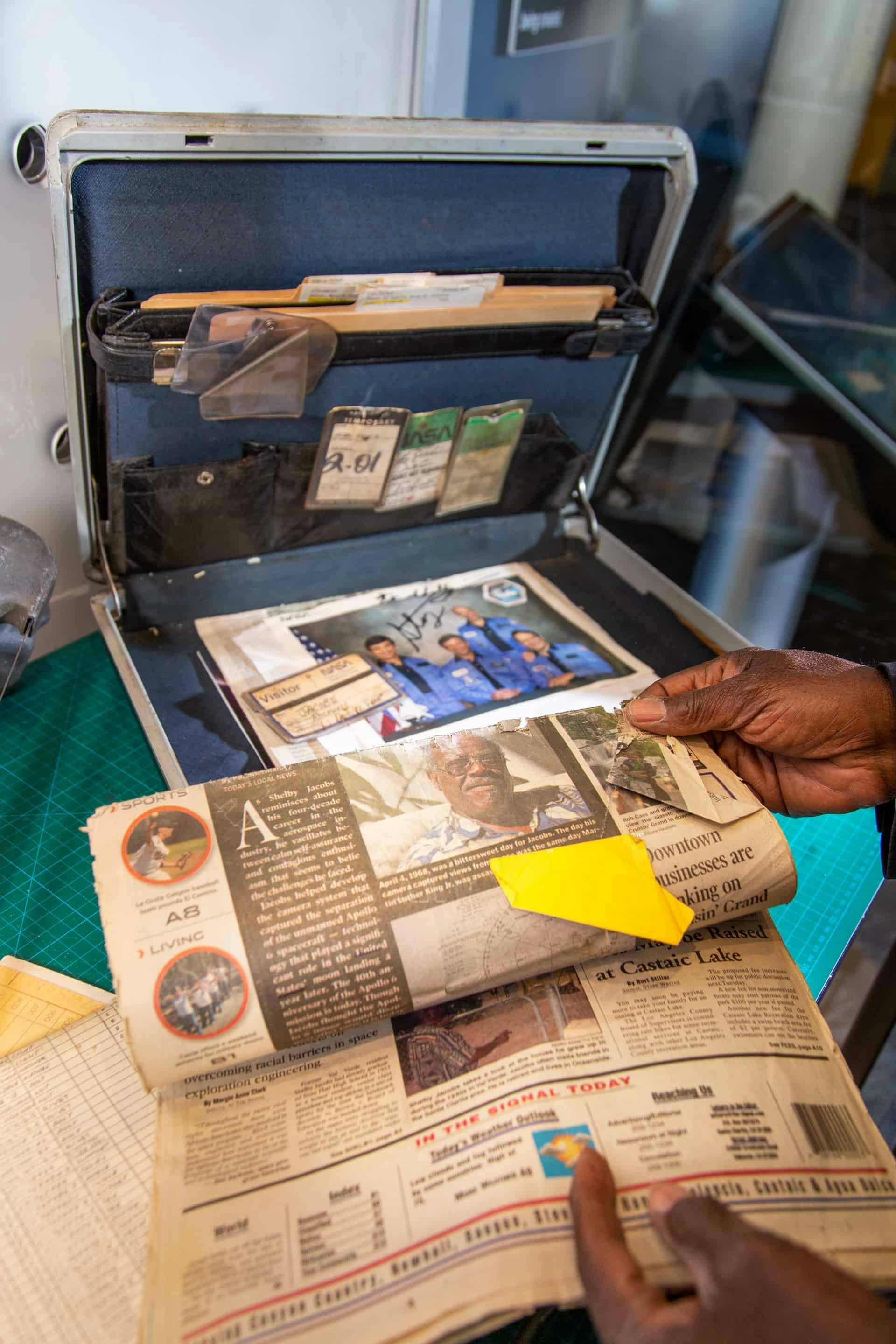

Ironically one Southern California pioneer, who’s achieved his dreams, actually followed a path that intersected with both of those American icons. 83-year-old Shelby Jacobs of Oceanside is being honored at the Columbia Memorial Space Center in Downey, with the facility’s first-ever exhibit dedicated solely to one man and his mission. It’s also the first time any space center has honored a black man. “The exhibit is beyond my wildest dreams,” says the modest engineer.

Breaking barriers has been part of Shelby’s life for as long as he can remember. Growing up in the white suburbs of the Santa Clarita Valley, he had no black role models at all. But that didn’t stop him from becoming senior class president and playing varsity in three sports. It was being a hurdler, in particular, that taught him the most valuable lesson. Exceling in science and math led to a scholarship at UCLA, where his goal was to study engineering. When Shelby’s school principal told him there were no black engineers and that instead he should “take a trade,” that’s not exactly what the ambitious senior heard.

Shelby says he translated the principal’s warning to mean that while the odds against success were considerable, that should not deter him. “Since I was a hurdler, getting over barriers is what I did. That’s much more difficult for a sprinter, so that’s why I chose to be a hurdler,” he explains. This attitude pushed Shelby to go for what he calls “success in spite of the odds.” And that is exactly what he did.

After three years of college, he joined Rocketdyne, a rocket engine design and production company based in Canoga Park, where he was one of only eight African-Americans in a workforce of 5,000.

In 1961 President Kennedy delivered his historic speech that set the United States on a course to the moon. The president said, “We choose to go to the moon not because it is easy, but because it is hard … because that challenge is one we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone and one which we intend to win.” Shelby didn’t know it at the time, but he would become an integral part of that victory.

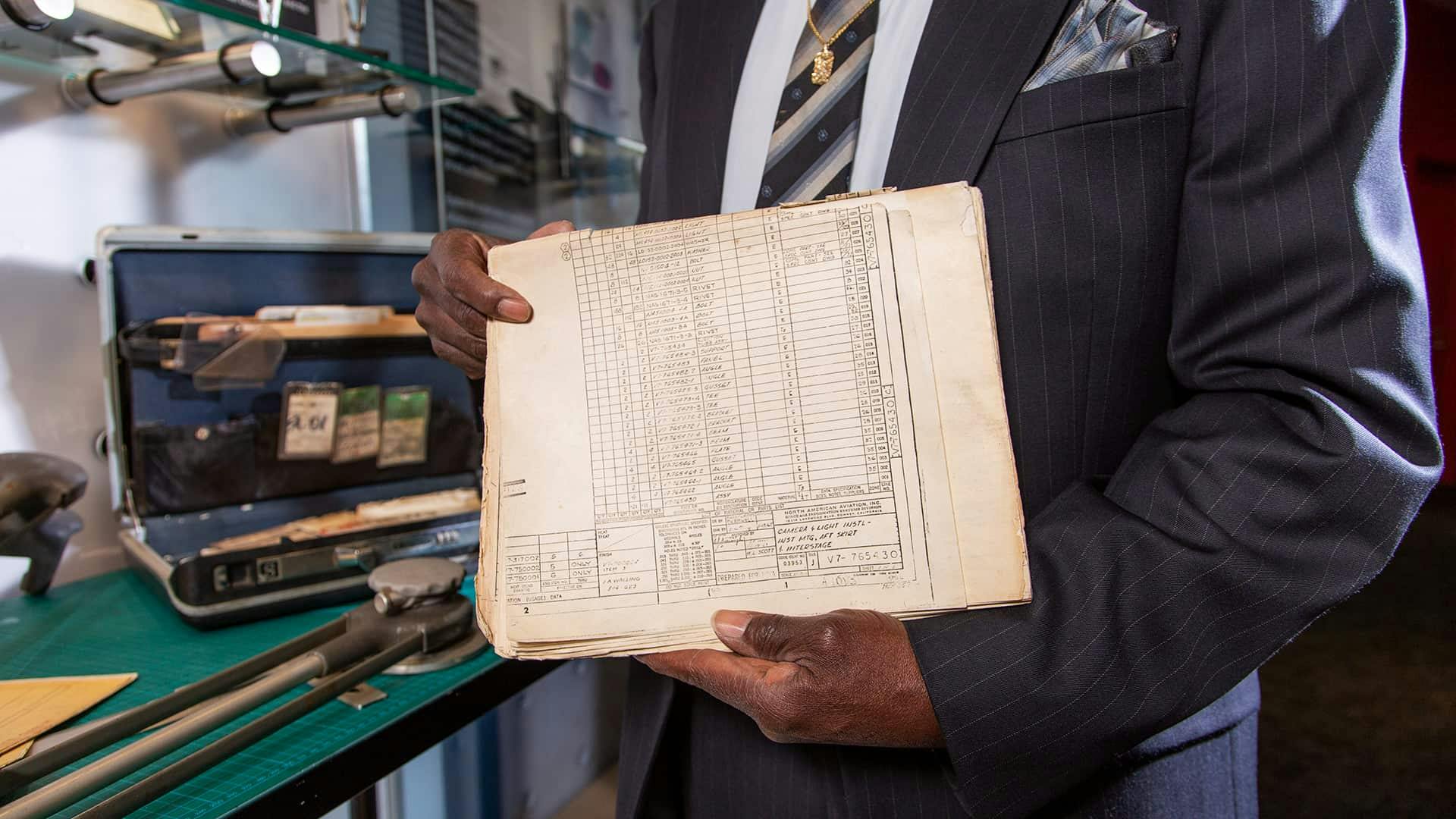

Later that same year, Shelby transferred to Rockwell in Downey, where he would spend the remainder of his career. With the space program fully underway, sending a man to the moon became a top priority. One of the biggest challenges was to make sure the various stages of a rocket could separate successfully before actually sending humans on a flight.

A team of mathematicians, similar to the women made famous in the movie Hidden Figures, did analysis and came up with a method to separate the first and second stages of a spacecraft, but NASA officials were skeptical. Shelby says their attitude was one of “show me.” Seeing this as just one more hurdle to overcome, he set out to deliver that proof.

On April 4, 1968, Apollo 6 was launched. On board the unmanned rocket was a camera system Shelby had designed in order to prove the necessary separation could be achieved. The footage taken by his camera not only proved the viability of the disengagement, but it revealed another, completely unexpected and exciting image. “Its purpose was to verify the separation, but in the process of doing so we captured the curvature of the earth,” explains Shelby. This was revolutionary, something never before seen by man.

Sounding as though it’s still hard to believe his invention documented the phenomenon, Shelby marvels, “It was monumental. The reason I’m being celebrated today is because the photo of the curvature took on a life of its own.” It became so iconic, in fact, that although the Kennedy speech was made in 1961, if you watch it today, you’ll often see editors have gone back and inserted that footage in the video. It was also used in the film Apollo 13. Shelby adds with a smile, “I would never have picked this particular event to define my career.”

As fate would have it, turns out another historic event took place on that very same April day—one quite the opposite, one that brought our nation to its knees. It was the day Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Strangely, Shelby had a connection to him as well. Three years before, he had spent the summer in Atlanta and Macon, Georgia, helping to set up the voter registration drive to register African-Americans. As Shelby puts it, “I was directly involved in civil rights, parallel with my aerospace career.”

Throughout that very successful career, he applied the same determination and inner strength that has always guided him—something Shelby repeatedly refers to as “divine intervention.”

He rose from being a junior engineer to becoming a project manager on “mahogany row,” an area of the company so named because of its elegant, luxurious desks.

But Shelby has never forgotten the racial barriers he had to overcome to succeed. He understands that he was a threat because whenever he moved up the ladder, he “took a seat that used to be occupied by a white man.” Today he uses the valuable lessons and experiences of his life to inspire and teach others. On the day we met, he was speaking to a group gathered at the Downey space center for a program to celebrate Black History Month.

While he readily acknowledges racism and sexism still exist in society and the workplace, Shelby appreciates that there has been enormous progress. Take for example the fact that when he worked at Rockwell in Downey during the 1960s, black people could not even live there. “It was considered KKK country, rednecks,” he says candidly.

But this wise man takes the long view, explaining that life and progress are like the stock market. “The trend has always been up, but it dips like a yo-yo. So I’m optimistic that when we come through this era, these last two years, we’ll get back on track to the progress. But right now this is a down cycle.”

In spite of today’s challenges, Shelby says he’s glad the problems are more out in the open and that people are saying things they wouldn’t have said in the past regarding their feelings about these sensitive issues. That, he believes, makes them easier to deal with. “Rather than being appalled by the fact that it’s there, I appreciate the fact that it’s highly visible. It’s like a fish in a punch bowl. You can’t miss it.

Shelby targets his message to people of color and women specifically. He believes generally females follow African-Americans in terms of progress and that both are still fighting for equality. “Imagine that 51% of the population makes 80 cents on the dollar,” he states. When it comes to advice, Shelby talks about a concept he refers to as “temperamental suitability,” saying it’s an element of success required by minorities and women. “Don’t allow the situation to anger you. Being angry is counterproductive and only hurts you. It does not solve the problem. Reserve your energy and apply it positively to the solution,” he counsels. And if you should succumb to those negative feelings, “Acknowledge that you got angry. Just don’t stay there.”

That’s not to say there won’t be many obstacles along the way. Shelby warns you should expect them. In his signature style, he explains it this way: “I say about bumps in the road—that’s why they make shock absorbers on cars, because there are bumpy roads. If the roads were all smooth, you wouldn’t need them.” Despite any roadblocks, he stresses one must remain optimistic. “It’s been worse than this. This is not even near what it was 50, 60 years ago. Everything I went through … all got better.”

Going back to that concept of divine guidance, Shelby says he has never doubted himself. Although it wasn’t something he was ever taught, he always knew he would prove his doubters wrong. “My job was to take advantage of every opportunity to demonstrate to them the contrary.”

When asked about his newfound fame, Shelby makes it clear his fame is not new. “I have always stood out. Having high visibility has just been my life. If you’re shy about being seen, you’re in trouble if you’re going to have any kind of pioneering role.” And this confident, yet humble man acknowledges he has been a pioneer from “day one.”

Well, almost day one. Shelby tells the story of when he was a 7-year-old moving from Texas to California. When he and his mother boarded a Greyhound bus, he took a seat behind the driver. His mom immediately guided him to the back of the bus. Reflecting on that moment, he says, “My struggle in life since then was to get from the back of the bus to the front of the bus. And where am I? I’m a lot closer to the front than the back now.”

You don’t have to be a scientist to know that’s a fact.

Achieving the Impossible: The Life and Dreams of Shelby Jacobs

When: Exhibit is open now through mid-March

Where: Columbia Memorial Space Center,12400 Columbia Way, Downey

Information: (562) 231-1200 or columbiaspacescience.org