The first time I met Simon was through a simple suggestion from a mutual friend: “Hey, you guys should meet one another.” Honestly, at the time I didn’t even really know what that meant, and the only real context I had was that he was a photographer living in San Pedro.

This all came about during a period in my life when there was time to meet a kindred spirit. Prior, it was wake up, cram as much stuff into one day as possible, lie down after it’s all over, pass out and do it all over again the next day. Fine for a season, but this season had a little more margin. There’s time.

Initially, I linked up with Simon on a text thread. “Come over whenever” is what I think his text said. “Whenever?” I thought. You mean we don’t have to do the mundane, back-and-forth dance around people’s overly scheduled days? That’s what I’m used to, so “whenever” caught me off guard.

“So there I am, in a garage in the back alley with a 6’6” man dressed in all black, wearing a black apron and black latex gloves, beers on the dryer, with a homemade bubbly water in my hand. Did it suddenly get hot in here?“

Within a couple of days, I found myself driving to San Pedro to meet Simon—on a simple whim from a very good friend who gave me the wink to say, “You must see to believe.” Prior to my arrival, Simon requested that I pull in the back alley. “Odd—front door doesn’t work?” I thought.

As I walked down the alley attempting to eyeball which backyard may be his, I saw a large figure emerge from the back gate. It seemed to have ducked under the entry’s overhang leading from the backyard into the alley. From my vantage point, I’d put the figure at around 6’4” to 6’6” tall.

I saw a silhouette turn my direction, and from the large shadow a long arm emerged like a tree branch extending from its trunk. Then the branch waved at me. This must be Simon, I thought. As I got closer, the figure kept waving. As I got even closer, I began to see that his hands were covered in black latex gloves that led into a black T-shirt, with a black apron, black shorts, thick black-framed glasses, a shiny bald head and a pair of Adidas Adilette slide sandals covering what had to be a size 13 foot.

“You must be Jared—nice to meet you,” he spoke in a very upbeat tempo. “You want a bubbly water? I make it myself.”

“Sure,” I said. But in my head: “You make your own bubbly water?”

I had heard that Simon was a craft beer lover and part of the early craft beer movement in Los Angeles (he is the creator of Phantom Carriage Brewing, for all you beer lovers out there). I too am a craft beer lover, so I brought a few nice bottles as a nice-to-meet-you offering.

As Simon was pouring the bubbly water, I said, “Hey, Simon, I brought some tasty beers for you to try. Not sure if you’d had any of these, but there should be enough here to get you through the next few days.”

Without looking up he said, “Oh yeah, cool. Stick ’em over there on the dryer.”

“On the dryer?” I thought. Interesting. Maybe the refrigerator was full?

“So, you drinkin’ anything tasty these days?” I asked. Figured it would be a nice icebreaker. He hands me the bubbly water and goes right into his refrigerator and pulls out a bottle.

“You know what, I am,” he said with some exuberance as he handed it to me. “This stuff is killer. In fact, drinking a bunch of it right now. It’s nonalcoholic.”

“Really?” I said.

“Yeah, sometimes I just like to trick my body and do a little experiment.”

So there I am, in a garage in the back alley with a 6’6” man dressed in all black, wearing a black apron and black latex gloves, beers on the dryer, with a homemade bubbly water in my hand. Did it suddenly get hot in here?

Nerves began to take over. Not much of this was making a whole lot of sense, and I’d only been there for five minutes. When nerves take over, my mouth runs. I yammered on about god knows what—my life, my career, my blah, blah, blah.

When I was done yammering, Simon just looked at me and smiled—almost to say, “Why did you just tell me all of that?” And then without hesitation, he followed it up with, “Want to go see the photo studio?”

“Uh … yeah … sure,” I said.

“Cool, follow me.”

We left the garage and started to walk up a flight of stairs toward the studio. On the way up, I noticed a vine of some sort twisting its way along the stairway banister. “Cool plant,” I said.

Clearly, the nerves still were defaulting to meaningless words, filling the air for no particular reason. Cool plant? Good grief, Jared. Pull it together.

“Oh yeah, that’s my Frontenac vine. It’s a Native American grape I use to make some pretty darn good table wine. I’m expecting about four gallons of juice this season from that baby.”

“Okay, is this dude messing with me?” I thought. Homemade bubbly water, nonalcoholic beer, grapes, homemade wine? What is going on here?

Just then Simon opened the door to his studio, and at a glance everything looked pretty normal. Backdrop, lights, desk, computer—nothing out of the ordinary except for one glaring difference.

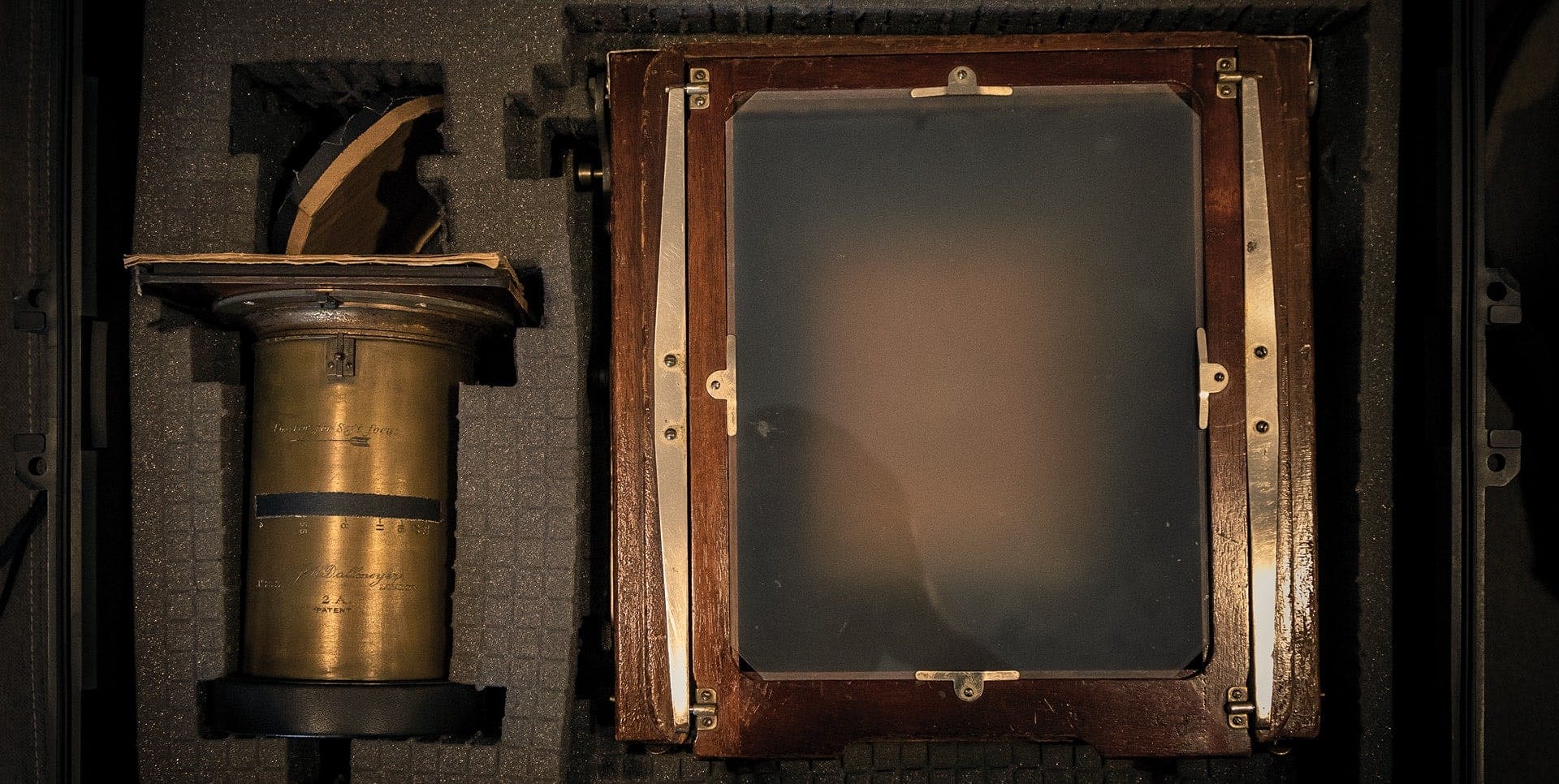

Simon does not use the latest and greatest camera body, lens, tripod, etc. He actually has reverted to a camera body dating back to 1918 and a lens that is made in 1878. More specifically, a Graflex Series DRV body and a Dallmeyer 2B lens, for all you photography historians out there. The type of photography Simon does is called the wet-collodion process—an early photographic technique invented by Englishman Frederick Scott Archer in 1851.

As Simon began to take me through the collodion process, it seemed to be a bit more of a chemistry experiment than anything else … consisting of adding soluble iodine to a solution of cellulose nitrate on a steel plate that is exposed to the camera while still wet and washed off with some sort of acid. I’m not going to act like I know exactly how it was all done. Simon was doing his best to walk me through the whole process, but a chemistry major I am not.

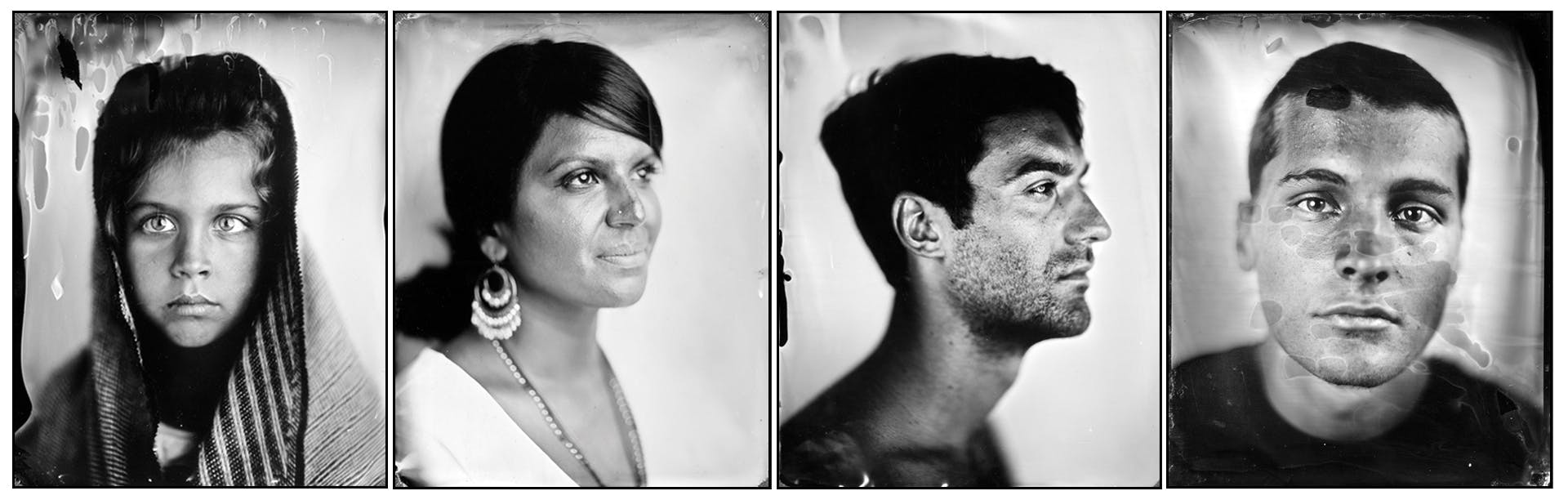

Then he held up one of his recent portraits, and I froze. I’d never seen anything like it. The level of detail, lights and darks mixed with an imperfect development process rendered an absolutely stunning piece of art. I just stood there trying to understand how such an archaic process could produce something so beautiful.

“Yeah, these types of photos last up to a couple hundred years,” he said while looking over my shoulder.

I stood there speechless. Nerves were gone because there wasn’t any more room for nerves. You know, that feeling when something grabs you with its beauty and forces you to just sit there for a moment. It’s like your brain is trying to understand what it’s looking at. Then it begins to understand this is no job for the brain but something only the heart can get its arms around.

One of my favorite quotes is by Pablo Picasso: “Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.” Somehow Simon with a camera from the early 20th century is able to pull something far larger from his subjects. A selfie pales in comparison.

Is it essence? Soul? I can’t quite explain it, but I know what I saw in that little garage photo studio in the back alley of San Pedro. Simon washed the dust of everyday life off my soul as I looked through his portfolio of subjects—most of whom I’ve never met, yet all had the same trait. They all possessed this inexplicable depth.

And it should be said: This is not Simon’s vocation. He’s a lawyer. I know. Crazy. A patent lawyer—and a successful one at that. Yes, one more thing to add to the mixed bag of idiosyncrasies that make Simon, well, Simon. So why does a lawyer moonlight as a colloidal wet plate photographer? It’s not cheap. It’s not easy. It’s awfully time-consuming and very complex. I couldn’t figure it out.

“Why, Simon?” I asked. “Why build out this studio, purchase all the materials and invest in a camera that feels like it belongs in a museum?” He just smiled and without hesitation said, “Because everyone deserves a good picture of themselves.”

You know, we live in a funny time. Tension is high. We are working through some major issues—things like division, racial injustice, gender inequality, the information era, fear, anxiousness, depression, health care and the endless pursuit of more. But then there’s this: a patent lawyer who understands the value of creating things for the betterment of another, and in this case it comes in the form of 19th-century-style photography.

So, yeah. Maybe we need to take a note out of Simon’s book. Make things. Make bubbly water. Grow grapes. Give someone a printed photo you took of them. Unapologetically march to the beat of your drum, because guess what … that beat is infectious.

Days after my time with Simon, I bumped into the mutual friend who had initially put us in contact. We immediately began to ping-pong on Simon stories. He proceeded to tell me about a time when Simon unexpectedly broke out a bottle of Pappy Van Winkle (premium bourbon for you nondrinkers) and poured them both a glass. No occasion. Just because. Could’ve even been the middle of the day.

I so wish I could have been there for that moment because I would have asked him, “Why did you just open a bottle of Pappy? What’s the occasion?” I bet his response would have been: “Because everyone deserves a good glass of bourbon.”