In a post-Occupy Wall Street society, still encroached by brewing conflicts in familiar, foreign locales, songs like “The Jewel of June” resonate with the same spirit of political protest that lingered in Simon & Garfunkel’s “Homeward Bound.” Prologue’s “There By Your Side” conjures that sense of longing and finality on The Sound of Silence’s “Leaves That Are Green.”

Throw in some smart business moves that resound with the free-spiritedness of the time, and you get an idea of how the duo has managed to strike such a chord with millennials and baby boomers alike.

Your on-stage banter with Kenneth sometimes seems as though it’s masking actual resentment.

Joey Ryan: It doesn’t mask the resentment; it reflects it. Sometimes in the middle of the tour we can get to each other—if so, then that’s pretty evident in the banter. When we’re on stage, everything is done for the sake of the audience. We are playing a show, and the audience comes first. But we’re still going to be honest with each other.

Was making those first two albums free a mutual decision?

JR: We both decided not to go through the traditional channels of the music industry. It didn’t make sense, especially since we were just starting out. We knew that if we sold it for money, it would be impossible to get a lot of our friends to buy it, even. We figured that this way, all our friends could get it for free, then all their friends could get it, and so on.

Would you say that’s a rookie mistake a lot of up-and-coming bands make—charging instead of giving the music away?

JR: I’ve got to be careful about what I recommend. [Making the first two albums free] is what worked for us. Nobody in the music business knows what works anymore. There’s no one reliable model; it’s completely unstable. That’s why we want people to download the album. We wanted it to be an experience. We think it’s important to get the tracks, all the artwork, to get everything.

Both albums ended up selling about 275,000 copies. It never crossed your mind how much you could have made, if you’d only charged even a little for them?

JR: No. It wasn’t what we were trying to do. In the end, it led us to where we are now, so it worked well.

You’ve remarked that you had an unsuccessful music career before you met up with Kenneth. Did you mean musically or financially?

JR: Both musically and financially. It wasn’t working. Not enough people were coming to the shows; not enough people were buying the albums.

How did you end up meeting with him?

JR: I went to one of Kenneth’s shows and told him that I really liked his playing and gave him one of my CDs. The next time I ran into him at one of his shows, he told me that he really liked it. We jammed and really—there’s been some tweaking, obviously, but what you hear now isn’t that much different from those first two days of playing together.

Getting back to the lyrics, though. Sometimes there’s a very intangible quality to them. They could be about love or about society and the state of the world. Like “The Jewel of June”—the lyrics to that have more of a traditional folk quality and still are kind of ethereal and vague.

JR: I actually feel like lyrically that song says a lot to me pretty directly. To me, it’s kind of (Kenneth’s) expression of political dissatisfaction. Especially at a time when he had just gotten his hopes up and then just kind of got disillusioned. Everyone just kind of went back to business as usual.

Obama?

JR: Not just Obama, but more broadly and socially. Political corruption and scandals and shit, everything else. I think the lyrics in that one are more self-explanatory than in other songs.

A lot of your songs, a lot of the time, it feels like there’s this longing in the lyrics. It’s like you’re missing somebody.

JR: It’s not always a specific person, but maybe an idea or an experience—a particular time or a creeping sense that something is not quite right. I could be wrong, but I don’t think Kenneth is always singing to a person. Whomever he’s saying goodbye to in “One Goodbye,” for instance, isn’t a person.

But in a way, you’re hitting the same notes lyrically with the younger generations. I know there’ve been lots of Simon & Garfunkel comparisons, but do you ever feel like you’re reaching out to a disillusioned people, kind of how they did?

JR: I don’t know if we are. (pause) It’s hard to quantify when you’re still so early in the process. There isn’t one voice that represents what we do. When we write the subject matter, what we’re trying to do is speak how we feel and articulate it: being 30-31 years old in America and just feeling that disconnect. I’m not super-sad anymore. But the dissatisfaction is still what spurs my lyrical inspiration. I never wrote other than what I was compelled to express lyrically, which is that something’s not quite right—whether it’s with a person or with society or a generation, whatever. But I never felt the need to write a song talking about how great everything is.

Do you find it more difficult to write songs, now that you’re more content?

JR: Yeah. I find that I really have to focus on the discontent in order to—maybe the dissatisfaction feels less all-consuming than it did when I was younger. But you’re still always looking for that cathartic process.

Q&A with Joey Ryan of the Milk Carton Kids.

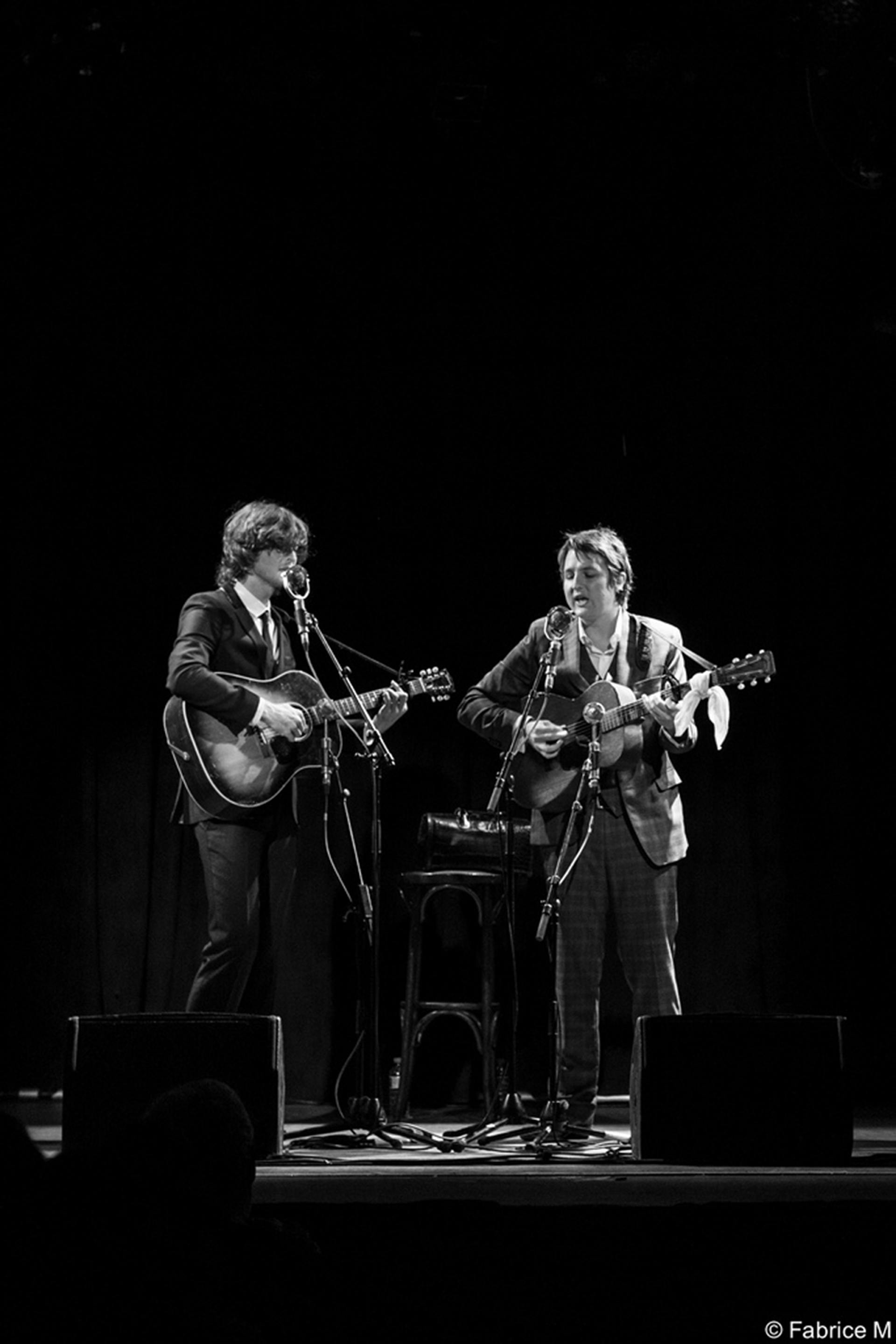

It might be impossible to see The Milk Carton Kids and not immediately think of classic ‘60s folk heroes—and with good reason. Their on-stage repartee may be the closest thing to The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

In their matching suits, Eagle Rock-based Kenneth Pattengale and Joey Ryan definitely give off a little bit of an Everly Brothers vibe. But perhaps what makes the Kids so relevant now is not only the sound they’re echoing but the spirit they’re channeling.

In a post-Occupy Wall Street society, still encroached by brewing conflicts in familiar, foreign locales, songs like “The Jewel of June” resonate with the same spirit of political protest that lingered in Simon & Garfunkel’s “Homeward Bound.” Prologue’s “There By Your Side” conjures that sense of longing and finality on The Sound of Silence’s “Leaves That Are Green.”

Throw in some smart business moves that resound with the free-spiritedness of the time, and you get an idea of how the duo has managed to strike such a chord with millennials and baby boomers alike.

Your on-stage banter with Kenneth sometimes seems as though it’s masking actual resentment.

Joey Ryan: It doesn’t mask the resentment; it reflects it. Sometimes in the middle of the tour we can get to each other—if so, then that’s pretty evident in the banter. When we’re on stage, everything is done for the sake of the audience. We are playing a show, and the audience comes first. But we’re still going to be honest with each other.

Was making those first two albums free a mutual decision?

JR: We both decided not to go through the traditional channels of the music industry. It didn’t make sense, especially since we were just starting out. We knew that if we sold it for money, it would be impossible to get a lot of our friends to buy it, even. We figured that this way, all our friends could get it for free, then all their friends could get it, and so on.

Would you say that’s a rookie mistake a lot of up-and-coming bands make—charging instead of giving the music away?

JR: I’ve got to be careful about what I recommend. (Making the first two albums free) is what worked for us. Nobody in the music business knows what works anymore. There’s no one reliable model; it’s completely unstable. That’s why we want people to download the album. We wanted it to be an experience. We think it’s important to get the tracks, all the artwork, to get everything.

Both albums ended up selling about 275,000 copies. It never crossed your mind how much you could have made, if you’d only charged even a little for them? JR: No. It wasn’t what we were trying to do. In the end, it led us to where we are now, so it worked well.

You’ve remarked that you had an unsuccessful music career before you met up with Kenneth. Did you mean musically or financially?

JR: Both musically and financially. It wasn’t working. Not enough people were coming to the shows; not enough people were buying the albums.

How did you end up meeting with him?

JR: I went to one of Kenneth’s shows and told him that I really liked his playing and gave him one of my CDs. The next time I ran into him at one of his shows, he told me that he really liked it. We jammed and really—there’s been some tweaking, obviously, but what you hear now isn’t that much different from those first two days of playing together.

Getting back to the lyrics, though. Sometimes there’s a very intangible quality to them. They could be about love or about society and the state of the world. Like “The Jewel of June”—the lyrics to that have more of a traditional folk quality and still are kind of ethereal and vague.

JR: I actually feel like lyrically that song says a lot to me pretty directly. To me, it’s kind of (Kenneth’s) expression of political dissatisfaction. Especially at a time when he had just gotten his hopes up and then just kind of got disillusioned. Everyone just kind of went back to business as usual.

Obama?

JR: Not just Obama, but more broadly and socially. Political corruption and scandals and shit, everything else. I think the lyrics in that one are more self-explanatory than in other songs.

A lot of your songs, a lot of the time, it feels like there’s this longing in the lyrics. It’s like you’re missing somebody.

JR: It’s not always a specific person, but maybe an idea or an experience—a particular time or a creeping sense that something is not quite right. I could be wrong, but I don’t think Kenneth is always singing to a person. Whomever he’s saying goodbye to in “One Goodbye,” for instance, isn’t a person.

But in a way, you’re hitting the same notes lyrically with the younger generations. I know there’ve been lots of Simon & Garfunkel comparisons, but do you ever feel like you’re reaching out to a disillusioned people, kind of how they did?

JR: I don’t know if we are. (pause) It’s hard to quantify when you’re still so early in the process. There isn’t one voice that represents what we do. When we write the subject matter, what we’re trying to do is speak how we feel and articulate it: being 30-31 years old in America and just feeling that disconnect. I’m not super-sad anymore. But the dissatisfaction is still what spurs my lyrical inspiration. I never wrote other than what I was compelled to express lyrically, which is that something’s not quite right—whether it’s with a person or with society or a generation, whatever. But I never felt the need to write a song talking about how great everything is.

Do you find it more difficult to write songs, now that you’re more content?

JR: Yeah. I find that I really have to focus on the discontent in order to—maybe the dissatisfaction feels less all-consuming than it did when I was younger. But you’re still always looking for that cathartic process.

Q&A with Joey Ryan of the Milk Carton Kids.

[tribulant_slideshow gallery_id=”5″]