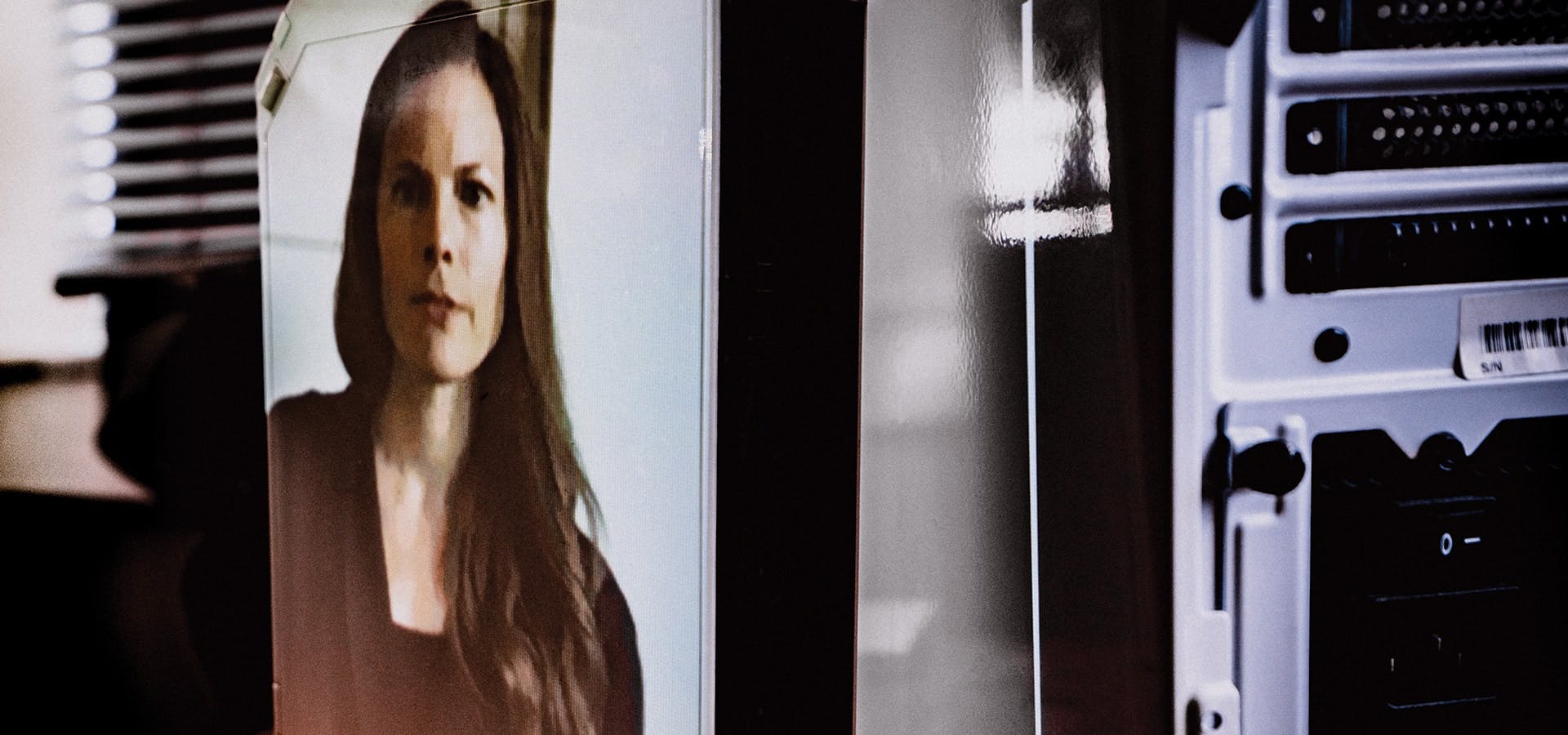

She can speak to this through line of interest both from personal experience (she mentions time spent living in the family car while growing up in Colorado, before moving to Los Angeles for college) and professional expertise. As Born explains how we arrived at 2020 levels of d/misinformation1 and what we can do about it, it’s clear how considerably her career has contributed to the field in which she now has a presiding role—as executive director of the Cyber Policy Center at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University.

That career kicked off with the Monitor Group, doing strategic planning for Fortune 100 companies, governments and nonprofits the world over. Her economic development and government work led to scenario planning with the NSA and CIA over national security questions (e.g., How left might Latin America go under Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez?).

Her interest in geopolitics led to a master’s degree in international policy at Stanford rather than a more mainstream MBA. Then she set off again for assignments abroad—consulting with the Vietnamese government and doing microfinance work in Paris with the World Bank.

1 Disinformation, as Born has defined in her paper “The future of truth: Can philanthropy help mitigate misinformation?” published June 8, 2017, is “intentionally false or inaccurate information that is spread deliberately, generally by unknown state officials, with a motive of undermining public confidence,” while misinformation is “unintentionally promulgated, inaccurate information, which differs from propaganda in that it always refers to something which is not true, and differs from disinformation in that it is ‘intention neutral.’”

After returning to the U.S. to have the first of her two daughters, she joined the Hewlett Foundation, eventually helping launch their democracy program, The Madison Initiative, under the direction of current president Larry Kramer. At the time, in 2012, the initiative was “the first major bipartisan philanthropic effort to improve U.S. democracy,” Born says.

“This was so far in advance of Trump and widespread recognition of U.S. polarization. It was really prescient of [Kramer]. I was excited to be involved because there were early signs then of deep polarization in the U.S. and no other major philanthropies were working on it from that angle,” she says, as opposed to a focus on emerging foreign democracies.

Born led Hewlett’s work on electoral reforms (like redistricting and ranked choice voting), civic engagement, media and money in politics. “Seeing so much more information consumption moving online, I became curious about how that was going to impact our democratic systems.” In 2013 she also began making her first grants to explore the effects of fact-checking.

Then the 2016 election happened. Public understanding of Russian interference via our new information ecosystems—from the misappropriation of personal data to the email hacking of Clinton campaign chair John Podesta and others—broadened. Simultaneously, “misinformation” entered the lexicon at large, joining “fake news” and then “alternative facts” and “post-truth politics” as Trump continued to foment distrust of the press.

By mid-2017 Born argued that philanthropy’s funding of journalism should shift to funding research on the impact of social media platforms. “We have quality information on climate change, on vaccines, and that’s not actually changing people’s minds,” she recalls of a focus on fact-checking and news literacy as ways to counter d/misinformation. “I think one of the biggest problems is suggesting that somehow citizens are going to solve this problem. We have the FDA for a reason. No one is going to sit down and try to understand the chemical compounds in shampoo.” 2

Rather than focus on the production of information or its consumption, Born focused midstream: on distribution. “That is the thing that has changed most fundamentally in our information ecosystem,” she says, pointing to the speed, scale, and ability to micro-target across social media platforms (and across multiple languages).

“Moreover, 95% of the ‘problematic’ content isn’t ‘fake,’” Born explains of the d/misinformation that would continue to evolve. “It could be a story that’s a little misleading, targeted at a minority group in a swing district with the intention to suppress votes or to inflame people around polarized issues.”

2 At the end of May, Twitter added fact-check labels to President Trump’s unsubstantiated tweets about mail-in ballot fraud, a significant step in policing misinformation from world leaders. In response, Trump filed an executive order to, in part, repeal Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects online platforms from liability for posts by users, and to enhance a Federal Trade Commission tool for “reporting online bias”—increasing the tensions between free speech and the digital age.

With an eye toward policy changes that could counter d/misinformation, research was needed to discover how much was out there, who was circulating it, and what impact it was having on voting beliefs and behaviors. As with any regulation, when it comes to tech policy, Born underscores a critical point: “Everything is a values trade-off. We want high-quality information, and we want free speech. We want privacy, and we want transparency and accountability.” And regulating around fundamental democratic or human rights values gets, she says, quite complicated.

Fortunately, others were coming to the table. Born was now hosting calls that had grown from including just two or three other funders before the election to every major funder in the U.S. interested in understanding the impact that the internet was having on our democratic information ecosystems. A pursuit of research revealed that data was sorely missing too.

“This is really the first time in human history that the richest data about how our societies are functioning is held by private companies,” Born says, rather than via academic survey or government census. “And they wouldn’t share it.”

Then Hewlett, along with Harvard, received a game-changing call from top Facebook leadership. The following week, on April 10, 2018, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg began testifying before congressional lawmakers about data privacy and Russian disinformation campaigns on Facebook. Zuckerberg agreed to give the data to a consortium of independent experts to analyze the impact that Facebook was having on elections and democracy globally.

“This was the birth of Social Science One,” Born says of the Facebook partnership turned scientific program between private industry and academic researchers that is now housed at Harvard’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. She became the funder chair and from the start was very intentional about wanting it to be a bipartisan effort, to not have fake news become a partisan issue like climate change. Funders including the Koch Foundation, the Arnold Foundation and the Sloan Foundation were asked to join.

Clement Wolf, Google’s global public policy lead for information integrity, has engaged with Born on several related initiatives including Social Science One and some of the first meaningful conversations between industry, academia, civil society and government. “She is very generous with her knowledge and has been a fantastic advisor,” Wolf says by email, pointing to Born’s “collaborative ethos” in particular. “The conversations she fostered laid the groundworks for research, analytical frameworks, or debates and discussions that continue to be relevant today; she has made it possible for organizations that had a lot to offer in terms of expertise and know-how to start specializing on this set of issues and become leaders in the field. And her relentless advocacy for the information needs of researchers and civil society has informed the perspective of many in industry over the years.”

Indeed, with unprecedented collaboration then underway at what Born describes as this “intersection of the internet, democracy and information ecosystems,” and with a Hewlett Foundation term limit approaching, she was also thinking about her next career move—from going to another philanthropy to a think tank to starting her own nonprofit.

Then Stanford Law School professor Nathaniel Persily, one of the three primary partners on Social Science One and a codirector of the Cyber Center, and Stanford professor of political science and director of the Freeman Spogli Institute Michael McFaul—the former U.S. Ambassador to the Russian Federation under President Obama, approached her about building what was then Stanford’s Cyber Initiative into the current Cyber Policy Center.

“Coming back full circle to my earliest concerns, the questions about who wins and who loses in the society that our children inherit are going to be heavily determined by questions around cyber policy,” Born says, citing examples from prison sentencing now being done algorithmically to online discriminatory pricing to gender- biased hiring algorithms, as well as unprecedented data collection on citizens’ health outcomes in light of COVID-19. “You’re looking at the introduction of this fifth domain of global conflict … before it was land, sea, air, space, and now any war will begin with cyber. So I came to feel that this is really the question of our generation: How do we govern these digital technologies in ways that uphold democratic principles and basic human rights?”

With Stanford’s roster of top scholars, Silicon Valley’s proximity to platforms and with the platforms themselves looking to academic research, Born saw where she needed to be to unpack and answer that question. In her founding director role at Stanford’s Cyber Policy Center, an impressive team has been assembled across six programs—all focused on the governance of digital technology at the intersection of democracy, security and geopolitics. In an election year, their work couldn’t be more pressing.

If hindsight really is 20/20, what have we learned and what are the new challenges? Born is well positioned to weigh in on some key differences. To begin, there is awareness and attention on the platforms themselves.

A community has also been built. “We have a field now,” Born continues of disinformation. “Before 2016 there were just a handful of us talking about this.” Now she helps host bimonthly calls with the top academic centers and think tanks around the country. Currently, their focus is on election planning as more election communications activities (from town halls to political ads) move online.

Third, there are frameworks for better understanding how manipulation campaigns work. Born points to Graphika’s chief innovation officer Camille François’ development of the “ABC framework” (Actor, Behavior, Content) at play in disinformation campaigns. “When we first started in the field in 2016, our frame was very much around content takedowns,” Born says of demoting or removing inaccurate information. “Since 2016 the field has moved to the A and B of the framework. Who is the actor? Is it a known disinformation operative? Is it a fake account? Regardless, these people shouldn’t be allowed to intervene in our information systems. Or B, the behavior component. If you are doing manipulative microtargeting, if you are running a bot network, if you are operating out of a troll farm, these behaviors should not be permissible.”

Taken together, the disinformation community can better understand how the current media ecosystem differs from past media ecosystems, opening up space around solutions.

With a continued focus on those solutions, Born had been planning, with the Aspen Institute Congressional Program, to host the first Aspen congressional delegation visit to Silicon Valley in March to tour the platforms and consider the ever-overlapping questions around data privacy, free speech, democracy and the internet. And then COVID-19 broke.

“I’m now hosting a series of webinars with thought leaders around the world to talk about how digital technology is being impacted and is impacting the current pandemic. My view is that the vulnerabilities and the opportunities that we are observing under COVID-19 are important in and of themselves to understand, but also have significant implications for those medium-term policy questions around the 2020 elections and long-term policy questions because we’re seeing how vulnerable these systems are—from Zoom to Facebook. Many of these companies’ #1 effort right now,” she says of such platforms, “is on monitoring mental health or self-harm on the platforms, or on shoring up server capacity so the whole thing doesn’t collapse because we have such a huge volume of people online.” But this takes attention away from content moderation in advance of an unprecedented election, where again (due to social isolation) more election activity will be moving online.

Born is also assessing the economic implications, as a concentration of power moves to online purchasing platforms and, as always, taking the geopolitical view. “You’re seeing massive new surveillance technology deployment—most of it, if you look at Hungary, China, without sunset clauses. There’s this argument: Is this the new 9/11? We had these massive government power grabs because people were in such a fear-based mindset, and then that power was never relinquished.”

In 2020, with an upcoming election, a global pandemic and a continued effort from numerous actors to undermine U.S. democracy—the only major presidential democracy in the world that hasn’t yet failed—the stakes couldn’t be higher for the questions Born is chasing.

“People will look back 50 or 100 years from now and say we, right now, determined the right infrastructure for governing our digital technologies—or we totally screwed it up,” she says of this disinformation arms race. “I think it’s all going to happen in the next five years.”

With Born and her A-team at Stanford—with their concern, understanding and access—we may just have our best shot at getting it right.

The People + the Programs @ Stanford’s Cyber Policy Center

-

Nathaniel Persily heads the center’s Program on Democracy and the Internet. Dan Boneh, professor in applied cryptography and computer security and codirector of the Stanford Computer Security Lab, serves as faculty codirector of the center alongside Persily. Frank Fukuyama, the Mosbacher director of Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, is working on antitrust and the platforms. Professor of political science Rob Reich, who directs Stanford’s Center for Ethics in Society and codirects the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, is teaching one of the first classes in the country on tech ethics. (This year, they will also graduate the first class of master’s in policy students with a cyber policy and security concentration.)

-

Director Alex Stamos, the former chief security officer of Facebook, and technical research manager Renée DiResta run the Stanford Internet Observatory, one of the world’s leading groups identifying coordinated manipulation campaigns globally.

-

The Global Digital Policy Incubator is under the direction of Eileen Donahoe, the former and first U.S. Ambassador to the UN Human Rights in the Obama administration, who with political sociologist and democratic studies scholar professor Larry Diamond looks at questions of human rights and the Internet.

-

As director of the Program on Geopolitics, Technology, and Governance, Andrew Grotto, who formally served as the senior director for cybersecurity policy at the White House in both the Obama and Trump administrations, works on security questions and runs cyber boot camps for staffers and journalists.

-

Daphne Keller, a former Google lawyer and a top intermediary liability expert, runs the Program on Platform Regulation, often critiquing new government policy and testifying before Congress (which many of her colleagues are also well-versed in doing).

-

As director of the Social Media Lab, professor of communication Jeff Hancock is looking at how new digital technologies affect social well-being and mental health.

-

“We have everybody,” executive director Kelly Born says of her team of about 40, which also includes the center’s international policy director Marietje Schaake, who served a decade in European Parliament working on technology, trade and foreign policy.