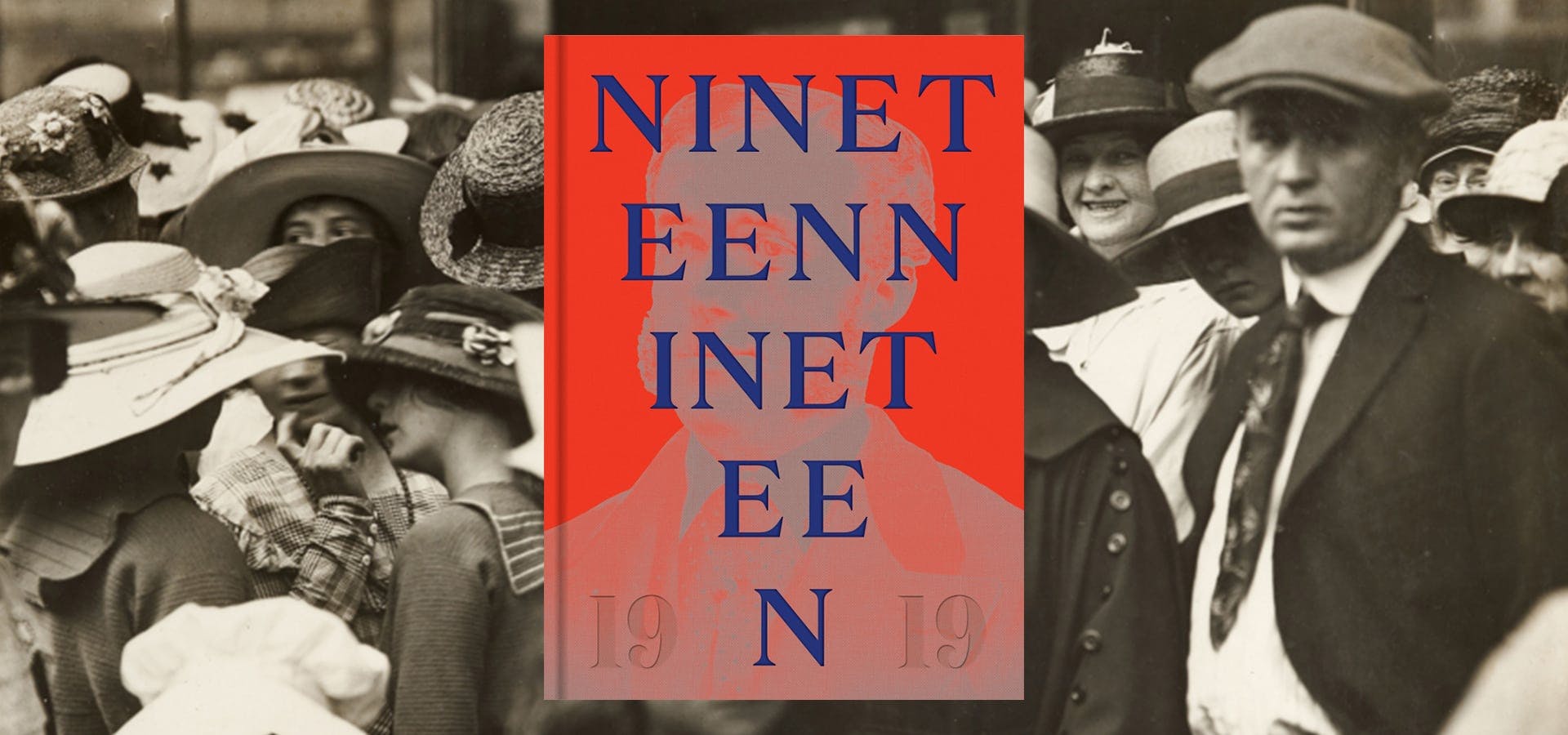

With objects as varied as posters from the German Revolution, abstract art, suffragist magazines, children’s books, aeronautic manuals, self-help guides for soldiers returning home from World War I, and a book hand printed by Virginia Woolf at her kitchen table, “Nineteen Nineteen” connects the generous act of two extraordinary Gilded Age collectors on their magnificent Southern California estate to the international aftershocks of a war that set the stage for the 20th century. When Henry and Arabella Huntington signed the trust document on August 30, 1919, that would transform their property into a public institution, the United States and Europe began their long recovery from World War I.

Henry Huntington was once asked whether he planned to write an autobiography describing his career. He demurred and said in response, “This library will tell the story; it represents the reward of all the work that I have ever done and the realization of much happiness.” When exhibition co-curators James Glisson, interim chief curator of American art, and Jennifer Watts, curator of photography and visual culture, were considering a Huntington centennial exhibition, they decided to take Huntington at his word and allow the library and art collections to tell the tale.

“This exhibition is not a historical account of the founders, though there are biographical elements threaded throughout,” said Watts. “We chose rather to look outward to the nation and the world, using The Huntington’s remarkable collections to tell the story of a single cataclysmic year. What better way to honor a 100-year anniversary of a collections-based institution than to excavate the collections that Henry and Arabella Huntington themselves began?”

“Nineteen Nineteen” is organized around five broad themes: Fight, Return, Map, Move, and Build, drawn from the millions of documents, objects, paintings, ephemera, photographs, and volumes found in The Huntington’s archives, galleries, and rare book stacks. “We wanted to harness the large number of 1919-related items here into something provocative, allowing the visitor to interpret the period in a fluid way. Rather than telling a neat, resolved story, we tried to recapture the jarring experience of life during a year that everyone understood was an inflection point for world history,” said Glisson. “Empires had fallen in the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Millions had died fighting and in a flu pandemic. Delegates at the Paris Peace Conference tried to sew a tattered world back together. Like today, people felt that irrevocable change was underway. The issues of 2019—immigrant detention, women’s rights, and the fight for a living wage—were equally pressing in 1919.”

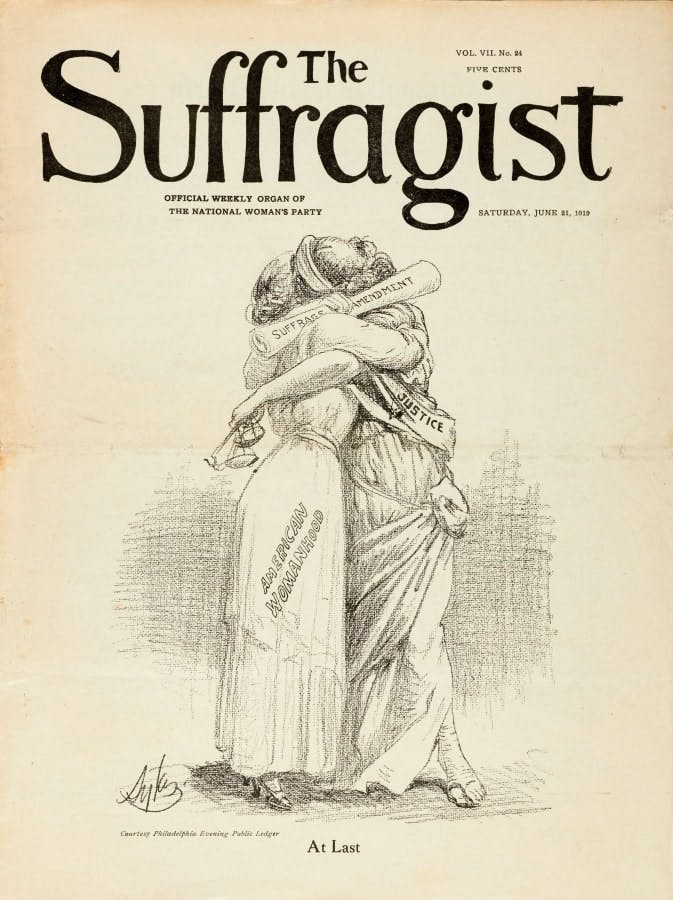

The “Fight” section of the exhibition shows that, while the war might have officially ended in 1918, other battles raged on in Los Angeles, the rest of the nation, and Europe. A global influenza pandemic killed millions of people, claiming three percent of the world’s population. Laborers agitated for better pay and safer conditions. Rumors about a Bolshevik plot to upend the U.S. government led to a Red Scare. Violence erupted in a season described as “Red Summer” for its deadly riots and lynchings of African Americans. In 1919, the bill that would clinch American women’s right to vote passed in the Senate, and temperance advocates won their fight for prohibition. Modernist artists and writers responded to the tremors of the age, including the carnage of world war, by breaking with convention and tradition. Materials in this section include rare German posters related to social and political upheaval; original photographs and materials documenting the flu pandemic in Pasadena, Calif.; national strikes and labor unrest; U.S. Marshal Records, (including mug shots and probation letters from German citizens jailed in Los Angeles during the war); and items telling the story of the fight to ratify the 19th Amendment.

“Return” focuses on the immediate aftermath of the Great War, when millions of men and women, including 200,000 African American soldiers, headed for home. Survivors sought to understand and memorialize the war’s events through personal reminiscence and published accounts. Artists, some of whom served overseas, interpreted what they had seen, while others found inspiration in canonical tradition and myth. Popular music and illustrated children’s books also offered safe harbor in tumultuous times. Objects from this section include Liberty Loan posters, soldiers’ reminiscences, a rare Edward Weston portrait of dancer Ruth St. Denis, Cyrus Leroy Baldridge’s illustration Study of a Soldier, and John Singer Sargent’s Sphinx and Chimaera, which depicts a mythological scene.

In January 1919, President Woodrow Wilson and Allied heads of state gathered at the Paris Peace Conference to make new maps of a changed world. The carving up of ancient empires created new nations in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Africa, while regional promoters published maps to highlight Southern California’s capacity for growth. High above Los Angeles at the Mount Wilson Observatory, the world’s largest telescope was on a nightly quest to chart the universe. In a world turned upside down, maps offered a welcome measure of predictability. The “Map” section of “Nineteen Nineteen” explores the meaning and power of charting territory that year. On view will be a first edition of Traité de Paix,the Treaty of Peace signed at Versailles on June 29, 1919, with a map showing new territorial arrangements; an album of autograph signatures gathered at the Paris Peace Conference by T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia); rare maps depicting population, transportation, and demographic data in Los Angeles and the nation at the time; and original astronomical photographs of the moon and constellations.

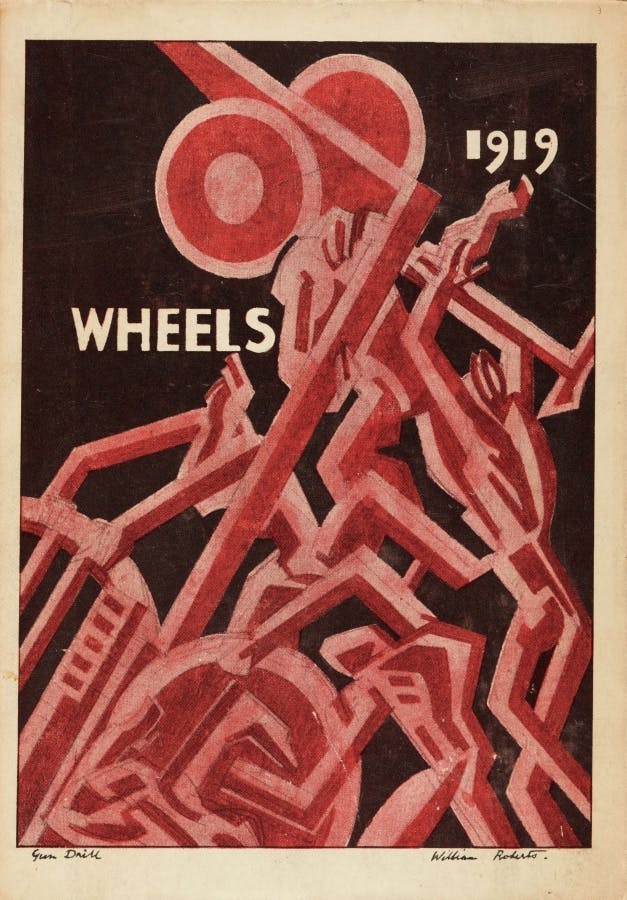

The “Move” section examines the ways 20th-century technologies—including planes, trains, and automobiles—propelled a society on the go. Henry Huntington’s network of streetcar lines famously brought Angelenos from “the mountains to the sea” and to far-flung deserts and farms. A burgeoning national road system made automobile travel possible and pleasurable as never before. Depicting the whirling nature of modern life, artists and writers gravitated to fragmented imagery and suggestions of movement to capture the disjunctive experience of the city.

The section spotlights the interstate automobile travels of five friends—including famed aviator Orville Wright—in a rare photographically illustrated volume titled “Sage Brush and Sequoia”; works by T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf, published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press; and a one-of-a-kind, 39-foot-long linen map created by the Pacific Electric Co. that depicts in meticulous detail the transportation and real estate networks running from downtown Los Angeles to Pasadena.

The final section, “Build,” focuses on Henry E. Huntington and the institution he created. In 1919, Huntington announced what some, including his New York librarians, had begun to suspect. He planned to load boxcars with the “world’s greatest private library”—some 120,000 volumes—and send it off to the nation’s far western shore. By then, the property’s palm, desert, rose, and Japanese gardens were planted under the guidance of William Hertrich. The mansion, designed by architect Myron Hunt, was completed in 1910. With the construction of the library building, the keystone fell into place for what would become the tripartite institution we know today.

Back in New York in December 1919, Huntington entertained members of the prestigious New York Authors Club at his Fifth Avenue home. At that exclusive event, he shared 35 of the treasures in which, according to his librarian, “he took especial pride.” The tantalizing selection offered the merest taste of the bibliographic cornucopia that the prodigious collector had assembled over 20 acquisitive years, providing our only insight into purchases he prized above all else. A few of the items showcased that night will be on display in the exhibition, including Benjamin Franklin’s handwritten autobiography, Maj. John Andre’s Revolutionary War-era maps, the first Bible printed in North America and in a native language, and the manuscript of Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman’s memoir. Also on display will be documents related to the early days of running the institution, including ledger books, book bills, library employee “report cards,” San Marino Ranch accounts, and photographs and architectural drawings documenting the construction of the Library building. There also will be an installation of George Washington artwork acquired by Huntington in 1919, including paintings by Charles Peale Polk and Gilbert Stuart.

For more on the exhibition and visiting the Huntington, go to www.huntington.org.