It was Linda’s first time paddling out at the famous break along the San Diego-Orange County line near Camp Pendleton, but that year had been one of notable firsts for the 15-year-old professional surfer. She’d competed in the West Coast Surfing Championships at Huntington Beach and won.

She then traveled to Hawaii and won the Makaha International. While she was there, Linda became the first woman to ride the massive waves at Waimea Bay on the North Shore of Oahu.

“It wasn’t huge,” the petite surfer (5’2” as an adult) says matter-of-factly, “but I think they were calling it at 18 feet.”

She snuck in with a few friends through the nearby marsh and paddled straight out. At the time, Trestles was used as a training ground for the U.S. Marines—it was strictly off-limits to the public until 1971. As soon as she got out into the line-up, she saw Dewey Weber, and everything changed.

“I couldn’t believe it,” says Linda, whose surfing style has often been compared to Dewey’s. “It was pretty magical.”

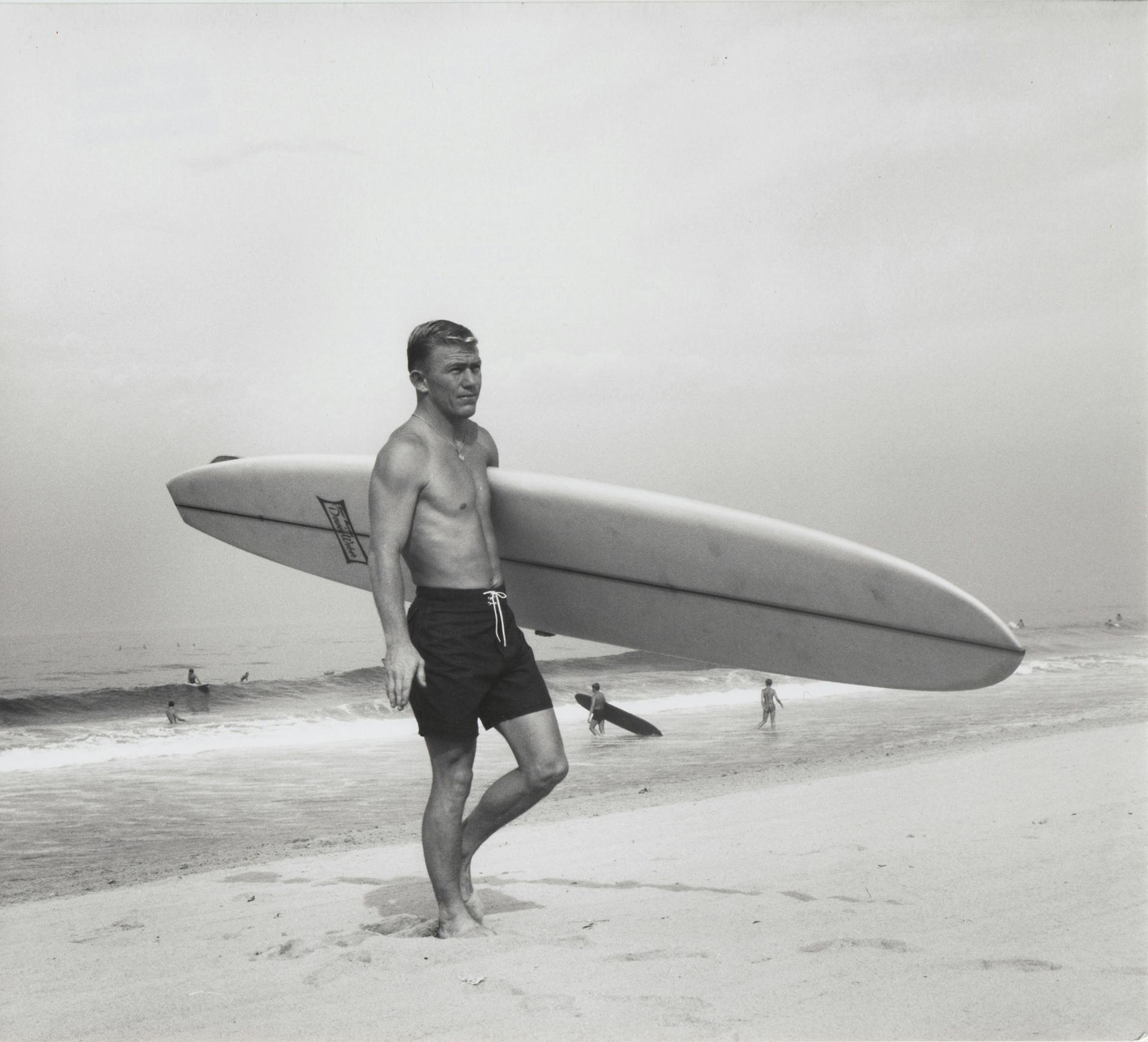

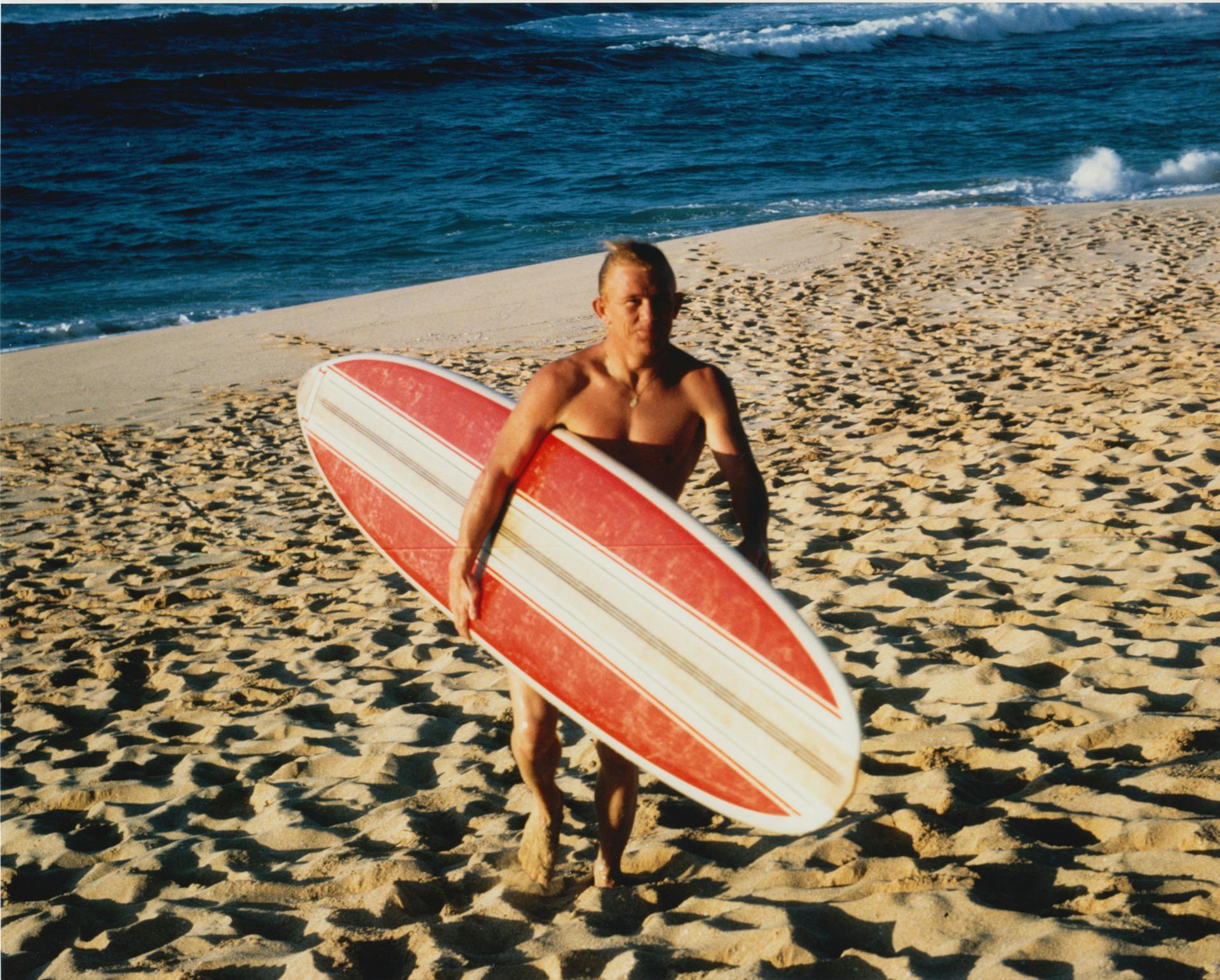

The flashy, bleach-blond surfer with the candy-apple red shorts was nicknamed “the Little Man on Wheels” for his agile footwork on a board. He’s considered to be one of the first “hotdoggers”—the flamboyant forerunners to today’s New School surfers and the first to add an element of flair and creativity to riding a surfboard.

Eventually, Marines showed up on the beach, shooting in the air to get their attention. Most of the surfers got the message and paddled back in.

She looked to Dewey for what to do next. He ignored the Marines and kept surfing. So she did too.

“We surfed, and they kinda kept firing. But for a while, it was just Dewey and I, and we had Trestles all to ourselves.”

After some time, they paddled back in. “They escorted us out, and they had a full-blown Marine tank right behind us—and I mean a few feet. It just followed us right on out. But I didn’t care if they put us in the brig.”

Both Dewey and Linda shared the same reaction to the whole affair. “We both just smiled.”

Best in the West

Dewey Weber, arguably the finest small-wave surfer to come out of the South Bay, epitomized the lifestyle and attitude of the Golden Era of Surfing in California—a time when longboards didn’t exist (they were simply surfboards). Malibu was considered the best wave in the world, and the South Bay was the focal point of surfing in the continental U.S.

In 1993, when he died at 54 from alcohol-related heart failure, it was a tragedy mourned by the global surfing community. His death was reported in the Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and every local newspaper in town.

Those closest to Dewey will tell you that he was fiercely competitive, well beyond the norm. From surfing to skiing and even yo-yoing (at age 14, he was a three-time national champion), he never slowed down.

Gerald Derloshon, author of Little Man on Wheels, a biography of Dewey Weber, notes that he had only “one speed: all or nothing, winner takes all.” When it came to surfing, he was thoroughly focused.

“When you saw Dewey Weber surf,” says former big wave surfer and shaper Greg “Da Bull” Noll, “you definitely knew you saw something special.”

Shelley Merrick, a former Weber employee and rider for Dewey’s “Redcoats” (named after their red nylon team jackets), remembers that wherever Dewey went, you would hear his ever-present key ring jingling on his belt, in tune with his constant hustle. “He was driven—a perfectionist. He never stopped moving.”

Dewey was the owner and founder of Weber Surfboards, which during the ‘60s was the sport’s second most popular manufacturer after Hobie Surfboards, thus cementing his status as one of surfing’s first millionaire manufacturers. Also, his surfboard model, The Performer, is considered the best-selling surfboard model in history, according to The Encyclopedia of Surfing by Matt Warshaw.

His life and career paralleled that of the South Bay surfing industry. He was there at its peak, along with others like Greg Noll, Hap Jacobs and Dale Velzy. When the industry unfortunately moved on, so did Dewey. But his impact on surfing, especially within the South Bay, can still be felt today.

Beginnings

Dewey was born in Denver, Colo., in 1938. At age 5, he and his family moved to Manhattan Beach, and four years later he started surfing. According to Gerald, Dewey the surfer “was born and bred on 22nd Street.”

Right from the beginning, Dewey was a natural athlete. In high school, he was a three-time all-league wrestler, but his diminutive frame (as an adult he was 5’6”, 130 pounds) often hindered him in football—he had trouble seeing over the linemen.

But in the water, his size never slowed him down. Capitalizing on his low center of gravity, and together with a talented crew of friends and future surfboard shapers like Bing Copeland, Hap Jacobs and Greg Noll, Dewey quickly became one of the top surfers in California. (Greg adds that the two met as Cub Scouts and that Dewey was a “smart little shit” and an “unbelievable goddamn surfer.”)

John Baker, a retired lifeguard captain, notes that it was Dewey’s speed and power that made him famous. He could perform a dizzying array of tricks, varying from walking the nose to carving hard cutbacks, “all in the manner of 8/10 of a second, and no one else could do that.” Dewey was featured in a number of popular surf movies in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, including Bruce Brown’s Slippery When Wet, Cat on a Hot Foam Board and Walk on the Wet Side.

Dewey’s skill caught the attention of surfboard-maker Dale Velzy, 10 years his senior. The two became close friends, and it was Velzy’s Pig design surfboard that helped the younger surfer develop his unique, rapid-fire style. Dewey would then go on to assist Dale at his surfboard shop in Venice.

In 1960, at 22, Dewey opened his first shop, Weber Surfboards, at the same location as Dale’s shop following its closure due to a tax conflict with the IRS. While specific details remain unclear, what is known for certain is that the two surfers had a falling out after the Venice location changed hands. They never reconciled their differences.

The Weber Triangle

“It became a partnership in every sense of the word,” says Caroline Weber, Dewey’s former wife. They met at a party in Hermosa Beach when she was 19 and he was 23. Together, they raised three children and built one of the largest surfboard manufacturers in California.

“I didn’t know who he was,” she says. A close friend explained that he was a famous surfer, and she remembers that people were eagerly drawn to his presence. She’d attended the party with another date and was only introduced casually to Dewey.

Later on, once they started dating, Dewey took Caroline to his house in El Porto to meet his roommate, Harold “Iggy” Ige. The three would later go on to form the core of Weber Surfboards—Harold as the gifted shaper, Dewey as the vivacious spokesperson and face of the brand and Caroline as the driving force behind the business. Dewey and Caroline were married on February 2, 1963.

During the ‘60s, almost all of the surf industry’s top manufacturers were located within the South Bay, with Hermosa Beach second to only Huntington Beach in terms of total surfboard production. From Mickey Muñoz to Mickey Dora, Los Angeles was at the heart of the sport on a national scale, and Weber Surfboards was right in the thick of it.

Dewey differentiated his company by focusing on branding, creating distinct, hatchet-shaped fins for his boards, matching red jackets and trunks for his team riders (members included Jackie Baxter, Mike Tabeling and Nat Young), and one-of-a-kind advertisements—something that was new within an industry that was generally low-key and more word-of-mouth.

“Dewey could’ve sold anything to anyone. He was a master salesman,” says Caroline, who also notes that Dewey was an equal opportunist. If you could do the job, you got it, no matter your gender.

Caroline often wrote the advertising copy, and the concept of giving their surfboards promotional model names was her idea as well. By 1966, the company was producing 300 boards a week, which was the same year Dewey was inducted into International Surfing magazine’s Hall of Fame.

Dewey continued to surf competitively as well, placing second in the 1964 United States Surfing Championships and winning the seniors division of the 1969 U.S. Championships.

Business was booming, and he used the profits to build a life with Caroline—and also fuel his love of cars. He bought a Ford Thunderbird for Caroline as a wedding gift, and later he purchased (in cash) a golden yellow Porsche 356 Coupe for himself. He and Harold would often speed up to Mammoth Mountain during the winter—Harold in his red Corvette, Dewey in his yellow Porsche—and race one another on the straightaways in the desert.

Caroline says, “He was ahead of his time, and that was his problem in life.”

The Shortboard Revolution

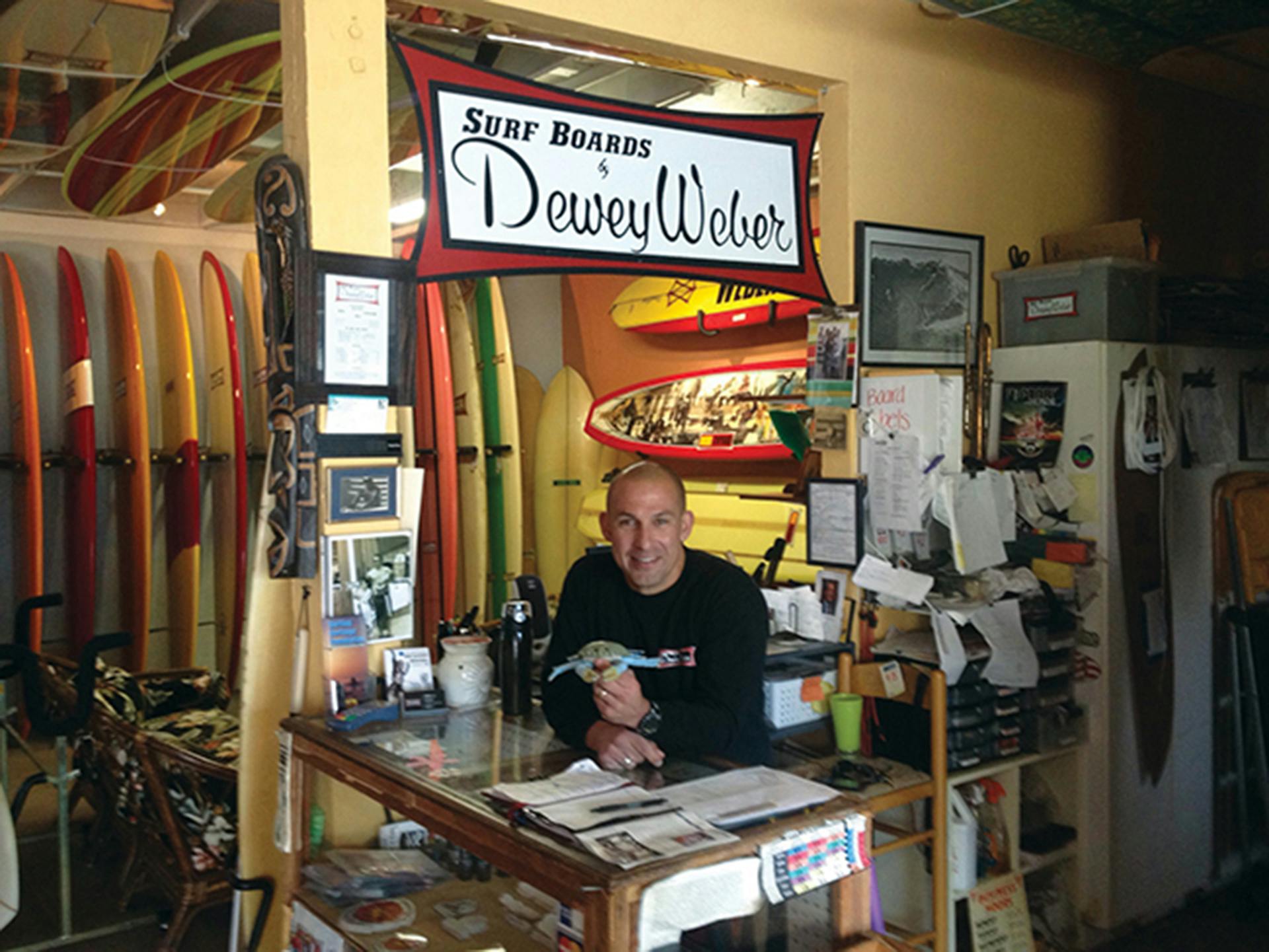

Shea Weber, Dewey’s son and current owner of Surfboards by Dewey Weber in San Clemente, looks to the snow industry to explain the impact of the late-‘60s shortboard revolution on the surfboard industry. “It would be as if when snowboarding came about, the entire snow industry stopped selling and making skis, and everything went to snowboards.”

While many of the classic South Bay surfboard shapers struggled to adapt to shaping the new board designs, Dewey pressed on. But his company faced two unforeseen challenges: the rise of backyard shapers and Dewey’s age.

“Let’s face it, these guys weren’t fundamentally business people. Maybe they didn’t see this tidal shift,” says Jeff Duclos, former mayor of Hermosa Beach. He explains that surfboard “blank” manufacturers starting selling raw materials to small-scale shapers who were more in tune with the changes in design. With little overhead (they were often shaping out of their garage), these shapers could crank out boards cheaply and sell their product at a reduced price—something the larger, more established shapers like Weber Surfboards couldn’t compete with.

But the most difficult challenge was that surfing, at its core, is a youthful sport. It has always been driven by a sense of teenage adrenaline and radicalism, and that was especially the case during the early 1970s.

Dewey, at age 30 and as the one of the top manufacturers in the country, was no longer a part of that mindset. He was the old guard, part of the establishment and a relic from an era that was, for most young surfers of that time, ancient history.

“He tried to be relevant,” says Gerald, “but he was the ‘man’—he was irrelevant.”

Dewey did his best to hang on, introducing new boards such as the shorter Ski model in 1969. But the consistent downturn took its toll. “He never envisioned that happening to him,” says Caroline.

“He never really learned how to lose or fail,” says Shea Weber. “He took it all so personally.”

Dewey picked up commercial fishing to help support his business, captaining a swordfishing boat he named the Avispa. But by that point, he had also begun to drink heavily. “Like everything else in Dewey’s life, he didn’t do it half-assed,” says Greg.

In the early 1980s, though, the Weber brand received a much-needed boost. With Caroline’s business mindset and Jeff Duclos’ assistance with public relations, the shop hosted the Peff Eick/Dewey Weber Invitational Longboard Classic in Manhattan Beach. Longboards were few and far between in any surfing lineup at the time, and Dewey is credited with initiating a gradual return to riding more traditional boards, spurring what’s referred to as the longboard renaissance.

However, Dewey’s drinking began to take priority, and in 1983, he and Caroline separated. Friends such as Linda Benson and surf photographer LeRoy Grannis reached out to Dewey to offer support. Greg Noll, whom Dewey called “Gorgy,” offered the use of his home in Northern California.

“I told him, ‘You can sit on the porch, watch the river go by. You can go down and get steelhead and salmon right in front of the house. We won’t talk about surfboards or any of that shit; we’ll just have a good time,’” says Greg.

“He got tears in his eyes and said, ‘Ah, I’m okay, Gorgy, I don’t have a problem.’” That was the last time Greg spoke to his friend. Dewey passed away in early January 1993, in a small apartment he rented behind his surf shop in Hermosa Beach.

The Legacy

“There’s never been anyone quite like him in surfing,” says Jeff. Aside from being one of the first “hotdoggers,” Dewey built a surfboard empire, and his surfboard, The Performer, is still in production today. (Shea notes that the design hasn’t changed much at all.)

Dewey’s true legacy is that he serves as a reminder of what the South Bay once was: the heart of surfing in California. He was the cornerstone of a legendary group of surfers and businessmen who built an industry that shaped a sport for decades to come.

There are currently plans for surf artist Phil Roberts to build a statue of Dewey in Hermosa, to commemorate his impact on the city and its surfing culture. Though Dewey’s era has passed on, it’s vital to remember that the sport owes a great deal to the Weber family, as well as those shapers and surfers from the Golden Era in the South Bay.

Without their achievements and sacrifices, surfing as the world knows it would be a far different—and far duller—creature.

A look back at the life, loss and legacy of California surfing icon Dewey Weber.

Linda Benson recalls that it was sometime in August 1959 that she and David “Dewey” Weber had Trestles all to themselves for a brief, but memorable, surf session. The day was hot—almost uncomfortably so. There was a light, dry offshore breeze, and the surf was head-high and glassy.

It was Linda’s first time paddling out at the famous break along the San Diego-Orange County line near Camp Pendleton, but that year had been one of notable firsts for the 15-year-old professional surfer. She’d competed in the West Coast Surfing Championships at Huntington Beach and won.

She then traveled to Hawaii and won the Makaha International. While she was there, Linda became the first woman to ride the massive waves at Waimea Bay on the North Shore of Oahu.

She then traveled to Hawaii and won the Makaha International. While she was there, Linda became the first woman to ride the massive waves at Waimea Bay on the North Shore of Oahu.

“It wasn’t huge,” the petite surfer (5’2” as an adult) says matter-of-factly, “but I think they were calling it at 18 feet.”

She snuck in with a few friends through the nearby marsh and paddled straight out. At the time, Trestles was used as a training ground for the U.S. Marines—it was strictly off-limits to the public until 1971. As soon as she got out into the line-up, she saw Dewey Weber, and everything changed.

“I couldn’t believe it,” says Linda, whose surfing style has often been compared to Dewey’s. “It was pretty magical.”

The flashy, bleach-blond surfer with the candy-apple red shorts was nicknamed “the Little Man on Wheels” for his agile footwork on a board. He’s considered to be one of the first “hotdoggers”—the flamboyant forerunners to today’s New School surfers and the first to add an element of flair and creativity to riding a surfboard.

Eventually, Marines showed up on the beach, shooting in the air to get their attention. Most of the surfers got the message and paddled back in.

She looked to Dewey for what to do next. He ignored the Marines and kept surfing. So she did too.

“We surfed, and they kinda kept firing. But for a while, it was just Dewey and I, and we had Trestles all to ourselves.”

After some time, they paddled back in. “They escorted us out, and they had a full-blown Marine tank right behind us—and I mean a few feet. It just followed us right on out. But I didn’t care if they put us in the brig.”

Both Dewey and Linda shared the same reaction to the whole affair. “We both just smiled.”

Best in the West

Dewey Weber, arguably the finest small-wave surfer to come out of the South Bay, epitomized the lifestyle and attitude of the Golden Era of Surfing in California—a time when longboards didn’t exist (they were simply surfboards). Malibu was considered the best wave in the world, and the South Bay was the focal point of surfing in the continental U.S.

In 1993, when he died at 54 from alcohol-related heart failure, it was a tragedy mourned by the global surfing community. His death was reported in the Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and every local newspaper in town.

Those closest to Dewey will tell you that he was fiercely competitive, well beyond the norm. From surfing to skiing and even yo-yoing (at age 14, he was a three-time national champion), he never slowed down.

Those closest to Dewey will tell you that he was fiercely competitive, well beyond the norm. From surfing to skiing and even yo-yoing (at age 14, he was a three-time national champion), he never slowed down.

Gerald Derloshon, author of Little Man on Wheels, a biography of Dewey Weber, notes that he had only “one speed: all or nothing, winner takes all.” When it came to surfing, he was thoroughly focused.

“When you saw Dewey Weber surf,” says former big wave surfer and shaper Greg “Da Bull” Noll, “you definitely knew you saw something special.”

Shelley Merrick, a former Weber employee and rider for Dewey’s “Redcoats” (named after their red nylon team jackets), remembers that wherever Dewey went, you would hear his ever-present key ring jingling on his belt, in tune with his constant hustle. “He was driven—a perfectionist. He never stopped moving.”

Dewey was the owner and founder of Weber Surfboards, which during the ‘60s was the sport’s second most popular manufacturer after Hobie Surfboards, thus cementing his status as one of surfing’s first millionaire manufacturers. Also, his surfboard model, The Performer, is considered the best-selling surfboard model in history, according to The Encyclopedia of Surfing by Matt Warshaw.

His life and career paralleled that of the South Bay surfing industry. He was there at its peak, along with others like Greg Noll, Hap Jacobs and Dale Velzy. When the industry unfortunately moved on, so did Dewey. But his impact on surfing, especially within the South Bay, can still be felt today.

Beginnings

Dewey was born in Denver, Colorado in 1938. At age 5, he and his family moved to Manhattan Beach, and four years later he started surfing. According to Gerald, Dewey the surfer “was born and bred on 22nd Street.”

Right from the beginning, Dewey was a natural athlete. In high school, he was a three-time all-league wrestler, but his diminutive frame (as an adult he was 5’6”, 130 pounds) often hindered him in football—he had trouble seeing over the linemen.

But in the water, his size never slowed him down. Capitalizing on his low center of gravity, and together with a talented crew of friends and future surfboard shapers like Bing Copeland, Hap Jacobs and Greg Noll, Dewey quickly became one of the top surfers in California. (Greg adds that the two met as Cub Scouts and that Dewey was a “smart little shit” and an “unbelievable goddamn surfer.”)

John Baker, a retired lifeguard captain, notes that it was Dewey’s speed and power that made him famous. He could perform a dizzying array of tricks, varying from walking the nose to carving hard cutbacks, “all in the manner of 8/10 of a second, and no one else could do that.” Dewey was featured in a number of popular surf movies in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, including Bruce Brown’s Slippery When Wet, Cat on a Hot Foam Board and Walk on the Wet Side.

Dewey’s skill caught the attention of surfboard-maker Dale Velzy, 10 years his senior. The two became close friends, and it was Velzy’s Pig design surfboard that helped the younger surfer develop his unique, rapid-fire style. Dewey would then go on to assist Dale at his surfboard shop in Venice.

In 1960, at 22, Dewey opened his first shop, Weber Surfboards, at the same location as Dale’s shop following its closure due to a tax conflict with the IRS. While specific details remain unclear, what is known for certain is that the two surfers had a falling out after the Venice location changed hands. They never reconciled their differences.

The Weber Triangle

“It became a partnership in every sense of the word,” says Caroline Weber, Dewey’s former wife. They met at a party in Hermosa Beach when she was 19 and he was 23. Together, they raised three children and built one of the largest surfboard manufacturers in California.

“I didn’t know who he was,” she says. A close friend explained that he was a famous surfer, and she remembers that people were eagerly drawn to his presence. She’d attended the party with another date and was only introduced casually to Dewey.

“I didn’t know who he was,” she says. A close friend explained that he was a famous surfer, and she remembers that people were eagerly drawn to his presence. She’d attended the party with another date and was only introduced casually to Dewey.

Later on, once they started dating, Dewey took Caroline to his house in El Porto to meet his roommate, Harold “Iggy” Ige. The three would later go on to form the core of Weber Surfboards—Harold as the gifted shaper, Dewey as the vivacious spokesperson and face of the brand and Caroline as the driving force behind the business. Dewey and Caroline were married on February 2, 1963.

During the ‘60s, almost all of the surf industry’s top manufacturers were located within the South Bay, with Hermosa Beach second to only Huntington Beach in terms of total surfboard production. From Mickey Muñoz to Mickey Dora, Los Angeles was at the heart of the sport on a national scale, and Weber Surfboards was right in the thick of it.

Dewey differentiated his company by focusing on branding, creating distinct, hatchet-shaped fins for his boards, matching red jackets and trunks for his team riders (members included Jackie Baxter, Mike Tabeling and Nat Young), and one-of-a-kind advertisements—something that was new within an industry that was generally low-key and more word-of-mouth.

“Dewey could’ve sold anything to anyone. He was a master salesman,” says Caroline, who also notes that Dewey was an equal opportunist. If you could do the job, you got it, no matter your gender.

Caroline often wrote the advertising copy, and the concept of giving their surfboards promotional model names was her idea as well. By 1966, the company was producing 300 boards a week, which was the same year Dewey was inducted into International Surfing magazine’s Hall of Fame.

Dewey continued to surf competitively as well, placing second in the 1964 United States Surfing Championships and winning the seniors division of the 1969 U.S. Championships.

Business was booming, and he used the profits to build a life with Caroline—and also fuel his love of cars. He bought a Ford Thunderbird for Caroline as a wedding gift, and later he purchased (in cash) a golden yellow Porsche 356 Coupe for himself. He and Harold would often speed up to Mammoth Mountain during the winter—Harold in his red Corvette, Dewey in his yellow Porsche—and race one another on the straightaways in the desert.

Caroline says, “He was ahead of his time, and that was his problem in life.”

The Shortboard Revolution

Shea Weber, Dewey’s son and current owner of Surfboards by Dewey Weber in San Clemente, looks to the snow industry to explain the impact of the late-‘60s shortboard revolution on the surfboard industry. “It would be as if when snowboarding came about, the entire snow industry stopped selling and making skis, and everything went to snowboards.”

While many of the classic South Bay surfboard shapers struggled to adapt to shaping the new board designs, Dewey pressed on. But his company faced two unforeseen challenges: the rise of backyard shapers and Dewey’s age.

“Let’s face it, these guys weren’t fundamentally business people. Maybe they didn’t see this tidal shift,” says Jeff Duclos, former mayor of Hermosa and a current city council member. He explains that surfboard “blank” manufacturers starting selling raw materials to small-scale shapers who were more in tune with the changes in design. With little overhead (they were often shaping out of their garage), these shapers could crank out boards cheaply and sell their product at a reduced price—something the larger, more established shapers like Weber Surfboards couldn’t compete with.

But the most difficult challenge was that surfing, at its core, is a youthful sport. It has always been driven by a sense of teenage adrenaline and radicalism, and that was especially the case during the early 1970s. “His life and career paralleled that of the South Bay surfing industry. He was there at its peak, along with others like Greg Noll, Hap Jacobs and Dale Velzy. When the industry unfortunately moved on, so did Dewey.”

Dewey, at age 30 and as the one of the top manufacturers in the country, was no longer a part of that mindset. He was the old guard, part of the establishment and a relic from an era that was, for most young surfers of that time, ancient history.

“He tried to be relevant,” says Gerald, “but he was the ‘man’—he was irrelevant.”

Dewey did his best to hang on, introducing new boards such as the shorter Ski model in 1969. But the consistent downturn took its toll. “He never envisioned that happening to him,” says Caroline.

“He never really learned how to lose or fail,” says Shea Weber. “He took it all so personally.”

Dewey picked up commercial fishing to help support his business, captaining a swordfishing boat he named the Avispa. But by that point, he had also begun to drink heavily. “Like everything else in Dewey’s life, he didn’t do it half-assed,” says Greg.

In the early 1980s, though, the Weber brand received a much-needed boost. With Caroline’s business mindset and Jeff Duclos’ assistance with public relations, the shop hosted the Peff Eick/Dewey Weber Invitational Longboard Classic in Manhattan Beach. Longboards were few and far between in any surfing lineup at the time, and Dewey is credited with initiating a gradual return to riding more traditional boards, spurring what’s referred to as the longboard renaissance.

However, Dewey’s drinking began to take priority, and in 1983, he and Caroline separated. Friends such as Linda Benson and surf photographer LeRoy Grannis reached out to Dewey to offer support. Greg Noll, whom Dewey called “Gorgy,” offered the use of his home in Northern California.

“I told him, ‘You can sit on the porch, watch the river go by. You can go down and get steelhead and salmon right in front of the house. We won’t talk about surfboards or any of that shit; we’ll just have a good time,’” says Greg.

“He got tears in his eyes and said, ‘Ah, I’m okay, Gorgy, I don’t have a problem.’” That was the last time Greg spoke to his friend. Dewey passed away in early January 1993, in a small apartment he rented behind his surf shop in Hermosa Beach.

The Legacy

“There’s never been anyone quite like him in surfing,” says Jeff. Aside from being one of the first “hotdoggers,” Dewey built a surfboard empire, and his surfboard, The Performer, is still in production today. (Shea notes that the design hasn’t changed much at all.)

Dewey’s true legacy is that he serves as a reminder of what the South Bay once was: the heart of surfing in California. He was the cornerstone of a legendary group of surfers and businessmen who built an industry that shaped a sport for decades to come.

“Dewey’s true legacy is that he serves as a reminder of what the South Bay once was: the heart of surfing in California.

He was the cornerstone of a legendary group of surfers and businessmen who built an industry that shaped a sport for decades to come.”

There are currently plans for surf artist Phil Roberts to build a statue of Dewey in Hermosa, to commemorate his impact on the city and its surfing culture. Though Dewey’s era has passed on, it’s vital to remember that the sport owes a great deal to the Weber family, as well as those shapers and surfers from the Golden Era in the South Bay.

Without their achievements and sacrifices, surfing as the world knows it would be a far different—and far duller—creature.

A look back at the life, loss and legacy of California surfing icon Dewey Weber.

[tribulant_slideshow gallery_id=”6″]