Growing up in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles, my first exposure to the instantly recognizable boned hand that is Body Glove’s logo was on a T-shirt. It was the late 1980s, and even my landlocked hometown had seemingly caught surfing fever.

Not that anyone I knew was surfing. Looking back, I realize it was probably the freedom, daring and sense of possibility that the logo represented that made it such a desirable piece of fashion iconography among my peers.

So often in this world of disposable marketing, a brand’s cachet is little more than a real-life case of “the emperor’s new clothes.” Madison Avenue executives take hold of a concept and build a merchandising empire around it, however briefly, and the fever that ensues is as inauthentic and insubstantial as the motivation that generated it.

The dust always settles at some point, of course, and when the buying public moves on, the world is left with dated artifacts that (at best) might lend their quirky charm to a time capsule buried in a school yard. In the case of Body Glove, however, it was the genuine dreams, passions and shared experiences of the Meistrell brothers that made their brand an enduring household name—not only for what it represents but also for the innovations and inroads that their company has made in the realms of surfing, diving and, ultimately, improving the world in which those activities take place.

According to Bob Meistrell, “People don’t work for me—they work with me.” Truer words are scarcely ever spoken, which is perhaps why the evolution of the Body Glove empire is so textured indeed.

When Bill Meistrell passed away in 2006 after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease, he left behind a familial and entrepreneurial legacy that continues to unfold almost as though he is still actively part of it. Both he and Bob founded Body Glove in 1953, inventing the first practical wetsuit while working as lifeguards and running their store, Dive N’ Surf, a South Bay institution even to this day.

Originally from Boonville, Missouri, the twins had moved to California with their widowed mother and five siblings to begin a new life in the wake of great tragedy. It’s the sort of American success story that is certifiably archetypal, until you begin to peel back the layers and discover the nuances that speak so uniquely of the Meistrell clan.

Bill Meistrell was born on July 30, 1928, followed by Bob 20 minutes later on July 31. It’s ironic that two twins who would “mirror” one another their entire lives, as Bob puts it, would not be born on the same day. But such are the fickle ways of fate.

Their life-long love of the water and shared athleticism was instilled in them at an early age at the recommendation of the family chiropractor. After caring for them during an early bout with pneumonia, he advised their mother to introduce them to swimming for its low-impact and overall composition-strengthening benefits.

Summers spent cleaning the local pool earned them coveted season passes and also enabled the boys to discover a passion for diving that culminated in the manufacturing of their own diving equipment for use at the local pond. Using an oilcan for a helmet and a bicycle pump attached to a garden hose for air, Bob admitted it was nothing short of a miracle that they didn’t die breathing the pressurized but poorly regulated air that was the best they could provide themselves with at that point in time.

Ingenuity and fearlessness were traits that exhibited themselves in both brothers early on, and upon learning this I quickly found myself pondering the question of nature, nurture and which of those two forces has the greatest influence on our lives. I am often wont to conclude that it is both, in equal measure, but my conversation with Bob imparted to me a sense of the role that active choices, made on a daily basis, have in synthesizing those two elements and determining the quality of one’s existence.

As I would soon learn, Bill’s and Bob’s adventure-filled afternoons at the local pond were preceded by a particularly unfortunate event, speaking volumes about the foundation upon which their lives were built. Before I spoke with Bob in 2009, I had already read that their father was murdered when they were just 4 years of age. I encountered that information as a sad footnote in a fairly straightforward biographical piece, and Bob’s retelling of the incident was nearly just as straightforward.

Their father, as it turns out, was a very successful lender back in 1932, and he operated a lucrative business at a time in history when the Great Depression made financial success of any kind something of a rarity. In a classic case of a working relationship that goes from bad to worse, his former business partner shot him in the back of the head to avoid paying him money that he owed him, adding insult to injury as he dragged his lifeless body into a safe.

Time would eventually reveal to Bill and Bob how magnanimous a man their father had been, particularly in the myriad stories that appreciative recipients of his services would later retell. During our interview, Bob chose to highlight one story in particular that seems to reveal volumes about the very spirit that drives his business even to this day.

Upon lending a certain gentleman $500, which Bob pointed out was a significant sum in the early 1930s, the gentleman inquired as to why he was not being handed a written agreement that would legally bind him to paying that amount back. The elder Meistrell’s reply to that question was a simple one: “I’m not asking you to sign anything because I know you are going to pay me back, since I am the only person in this town who will lend you that money in the first place.”

The recipient of the loan did pay him back, after going on to build a business that grew and supported him for many years. Similar displays of sheer confidence wind their way throughout the story of the Meistrell brothers and the unfolding of their businesses. This indicates that perhaps the family possesses a natural inner fortitude that is perpetrated by each generation’s examples to the next.

In the aftermath of their father’s death, Bill and Bob’s mother picked up where her husband left off, making ends meet by doing the best she could to collect the money people owed them. Her efforts were temporarily intercepted by a second husband who robbed the family of nearly everything they had.

I didn’t even press Bob for the details of that little drama, because in the context of Bob’s discourse with me, they appeared to be just that—little. By this time the brothers were 16 years old and poised to begin the next phase of all of their lives.

Along with their mother and all five of their siblings, they moved to California, in no small part at the behest of their mother who, like her children, was not inclined to remain stationary in the waters that were now flowing so quickly under the bridge. What transpired in the years that followed is what you can read about in the history books, although in doing so one might incorrectly conclude that founding, growing and sustaining a multi-million dollar business requires only a few good ideas and some gumption.

The analogy that immediately comes to my mind is the experience of watching figure skaters on television—their grace is such that their movements appear almost easy, inspiring you to believe that if you decided to hit the rink the next day, you could simply and quickly replicate their movements. Such is the illusion.

It should be stated at this point in the story that Bill and Bob had three boyhood goals (all of them achieved, by the way): to own a submarine, to go deep-sea diving and to go treasure hunting. Once they began making wetsuits, they added a few more goals to that list. They were as follows: to never live more than five miles from work; to make “a little money”; to have fun; to make a great product; and to service it.

In other words, they never intended to make history or, for that matter, to build a worldwide business. Therein, stated Bob, is the secret of their success, which is defined by happiness and a satisfaction with life that cannot be bought. Bob received confirmation that he was succeeding in communicating this to the younger generation when, after giving a talk at Anaheim University, a young man in the audience came up to him to say that having fun in his work, not chasing dollars, would now become his goal.

Bob pointed out to me during our interview that he and Bill did not invent the wetsuit; a man by the name of Hugh Bradner did. They simply improved upon it and made it a relevant piece of gear for surfers instead of just divers.

After moving to California, the brothers quickly picked up surfing, playing football and swimming while attending Redondo Union and then El Segundo High School. They soon became acquainted with the surprisingly cold currents that flow down the coast of this state so known for its warm weather.

They were among the first surfers to add fiberglass to the noses of their surfboards for protection, and during these years Bill sold legendary surfer Greg Noll his first surfboard. The only time the brothers were ever separated from one another was when they were drafted into the Army, with Bill being sent to fight in Korea while Bob was stationed in Monterey.

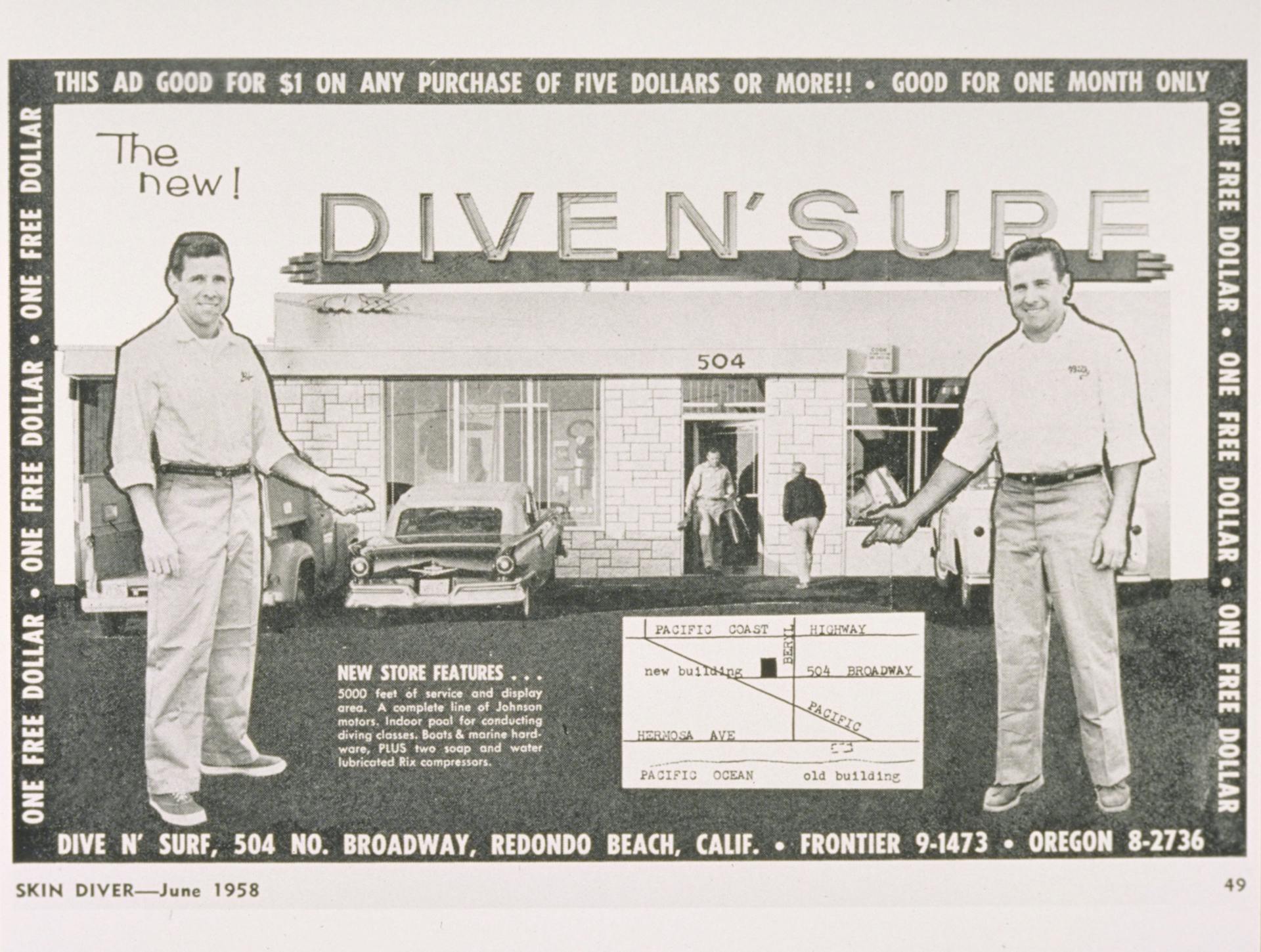

When Bill returned from Korea in 1953, they bought into Dive N’ Surf, which was owned by their friend Bev Morgan. Their mother lent them $1,800 for this endeavor, which only generated $.15 from a magazine sale on their first day of business.

They soon determined that selling $100 worth of merchandise per day would enable them to build a comfortably running business. For several years they had to lifeguard on the side to survive as they worked toward achieving that goal.

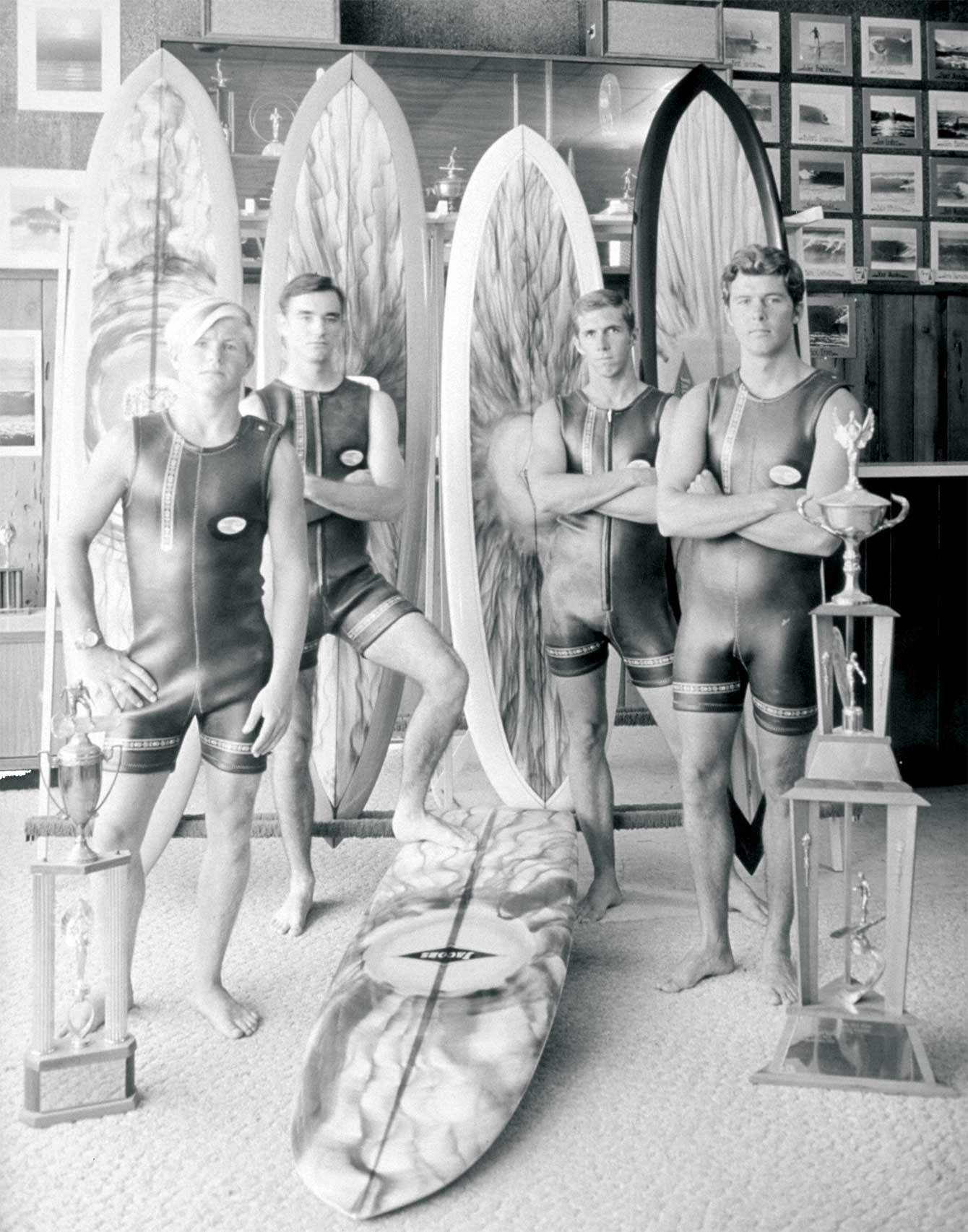

It was during this period that they developed relationships with such legendary watermen as surfers Bing Copeland, Rick Stoner, Dale Velzy, Hap Jacobs and Dewey Weber, all of whom shared with the Meistrell brothers a belief that surfing could one day become a highly regarded sport. They began building wetsuits, ingeniously discovering that lining the insides of wetsuits with neoprene (a substance found on the backs of refrigerators) enabled the body to better retain heat.

Soon after, Bill would venture to the town of Bedford, Virginia and, after visiting a company by the name of Rubitek, happen upon a soft and stretchy fabric that was used to manufacture the Pontiac station wagon’s taillight gaskets. Surfing would never be the same again, as the brothers would soon begin making wetsuits with this fabric since it allowed for far more movement than the stiff wetsuits traditionally worn by divers.

When Bill told their marketing consultant Dick Boyd “it fits like a glove,” the name Body Glove was born. The brothers paid a mere $35 for a hand-drawn sketch of the logo that is now world-famous. Bob pointed out that when he and Bill were inducted into the Surfing Hall of Fame in 1990, it was not because they were among the best surfers the world had ever known but because they improved upon a technology that prevents surfers from drowning, in addition to keeping them warm so they can spend hours (instead of just minutes) in the water.

Ever the true watermen to the core and well-respected to boot, Bill and Bob were asked to serve as consultants for the television drama Sea Hunt starring actor Lloyd Bridges. The program debuted in 1958, one year after they bought Bev Morgan out of his portion of Dive N’ Surf.

After watching the pilot, Bob told the producers that it could become one of the biggest shows in the world, but that it also exhibited a lot of technical mistakes that threatened its authenticity. During the program’s highly successful three-year run, Bill and Bob built Lloyd Bridges’ diving suits and, unbeknownst to many at the time, actually taught him to dive.

Bob informed me that at first Lloyd’s diving scenes were performed by a stunt double. In his off-time, Lloyd would find excuses to avoid people’s invitations to join them on dives. Once the brothers taught him to dive, he performed all of his own stunts and even entrusted his entire family to Bill’s and Bob’s instruction.

The Meistrells would eventually teach such stars as Gary Cooper, Charlton Heston, Hugh O’Brian and Jill St. John to dive as well, befriending these stars while continuing to hone their product and joining the Hollywood scene only peripherally.

Although their businesses have grown steadily and strongly since their inceptions, the brothers did encounter setbacks over the years that Bob referred to as learning experiences and not failures. Among them was a decision to create wetsuits in an array of colors, which almost drove them into bankruptcy because the dye degraded the foam. One would imagine it would be nearly impossible to avoid all such occurrences when breaking technological ground, but perhaps it is even more difficult to maintain the strength of vision and composure that enables one to press on and flourish when such setbacks occur.

One of Body Glove’s taglines over the years has been “protect the core,” and it seems that the Meistrell family has done this both literally (with wetsuits that do just that) and figuratively. The business is still very much family-run, with Bill’s son Bill, Jr. serving as vice president and Bob’s son Robbie serving as CEO.

As Bill, Jr. was quick to point out to me, most family-run businesses do not survive the first generation. The Meistrells are now entering their third generation of family ownership of both Dive N’ Surf and Body Glove, and he believes it is because they continue to base their decisions on the foundation that Bill and Bob built.

The fact that Bill and Bob actually fought like an old married couple on a regular basis is beside the point, since a spirit of mutual respect that transcended their differences regularly diffused their arguments. Bill preferred avoiding interviews in favor of building wetsuits in the back of the store, while Bob thrived on organization and interacting with the public. They realized, however, that their different preferences in regards to growing the businesses were completely necessary for their survival—and that very thought process governs their working relationships today.

Also governing the direction of the business is a people-first, grassroots approach to growth that is intimate and hands-on. It is probably for this reason that the city of Redondo Beach declared that October 1, 2006 would be Bill Meistrell Day after he passed. That’s how familiar this family is to the South Bay and Southern California at large.

Rather than investing millions of dollars in advertising the way some companies do, Body Glove opts to spend those dollars on its employees in exchange for a guerrilla approach to marketing that has proven highly successful.

The Body Glove logo continues to be highly recognized, in no small part because Bob’s son Ronnie regularly drives the Body Glove bus all over the country. On these trips he visits all of the stores that carry Body Glove products, forging stronger relationships with shop owners and introducing himself to potential customers along the way.

Bill, Jr.’s daughter Jenna is the first member of the family to graduate from college with a degree in business and a minor in communications. According to her father, she is also an expert communicator and a certified diving instructor like her great uncle, Bob.

Also in the people-come-first vein, the family places a very high premium on philanthropy and giving back to the community. Bob raised approximately $150,000 for charity annually for numerous organizations, offering catered day trips on the Body Glove boat in which he provided the crew, gas and other various aspects of his expertise as a local and a waterman.

He helped raise $22,000 for a replacement of the George Freeth statue that was stolen from the Redondo Beach Pier. He galvanized the collection of scrap metal with which to help create a new one and even offered a $5,000 reward for the return of the original. The original, decades-old mold was located, and this iconic piece of South Bay art commemorating the father of modern surfing was restored to its rightful place in the city.

As the hours passed during my 2009 meeting with Bob at his home and twilight began to descend, I felt compelled to ask him a potentially weighty question. Specifically, I wanted to know when Bob felt most in awe of the sea. Surely in all his years traversing the globe, he must have had moments of awe.

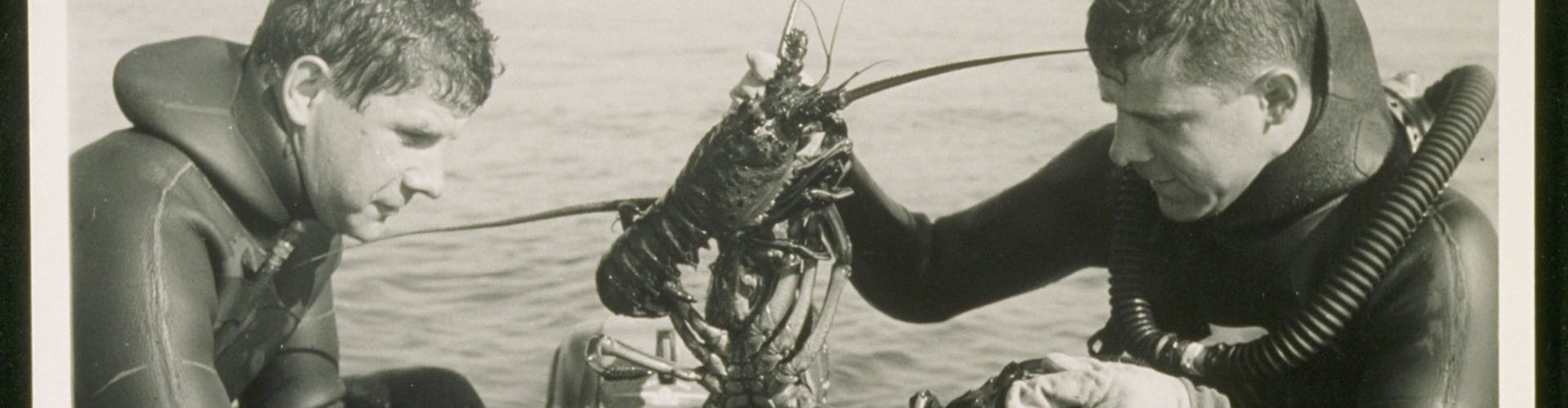

What ensued was a tangent that took the better part of an hour, culminating with a tour of his extensive seashell collection and an introduction to two Chinese stone anchors that he found off the coast of Catalina that date back to 4,000 B.C. He spoke to me of encountering a lobster bullring during mating season, when he witnessed two bulls surrounded by upwards of 40 female lobsters.

And then, of course, there was the time that a 20-foot-long great white shark soared over him as he lay flat against the surface of a rock under seven feet of water. I was also somewhat blown away when he told me about the 226-pound, six-foot-long sea bass that once dragged him through the water after he speared it, which inspired him to call for a moratorium on the sport after a fishing club followed his example and decided to take out an entire herd in one weekend.

What I realized from these anecdotes is something about Bob that I had already learned: Experiences that some people would be thoroughly intimidated by are considered integral aspects of his life story. I also learned that Bob ultimately favored a harmonious approach to coexisting with nature, in which hunting never reaches the level of species decimation but occurs at educated intervals to promote balance in the ocean.

By our interview’s end, Bob kindly invited me to join his family for dinner, only after informing me that not two days later he would be leaving for a weeklong expedition to Mexico, where both he and Jenna would be diving with (you may have guessed it) sharks. They say youth is wasted on the young, but clearly that saying does not apply when you are Bob Meistrell and your years scarcely dimmed your light at all.

That light would go out on June 16, 2013, just off the coast of Catalina Island. A fittingly glorious summer day, Bob had set out on his 72-foot yacht, Disappearance. He was a young 84. Smooth sailing, Bob.

Bob Meistrell made an indelible mark on worldwide beach culture with his late twin brother, Bill, when they created the brand Body Glove. For Bob and his clan, the future remained a vast expanse of blue waiting to be discovered. Not quite a year after his passing, a writer recalls her first meeting with Bob in 2009, when it seemed impossible the sun could ever set on his endless summer.

Growing up in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles, my first exposure to the instantly recognizable boned hand that is Body Glove’s logo was on a T-shirt. It was the late 1980s, and even my landlocked hometown had seemingly caught surfing fever.

Growing up in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles, my first exposure to the instantly recognizable boned hand that is Body Glove’s logo was on a T-shirt. It was the late 1980s, and even my landlocked hometown had seemingly caught surfing fever.

Not that anyone I knew was surfing. Looking back, I realize it was probably the freedom, daring and sense of possibility that the logo represented that made it such a desirable piece of fashion iconography among my peers.

So often in this world of disposable marketing, a brand’s cachet is little more than a real-life case of “the emperor’s new clothes.” Madison Avenue executives take hold of a concept and build a merchandising empire around it, however briefly, and the fever that ensues is as inauthentic and insubstantial as the motivation that generated it.

The dust always settles at some point, of course, and when the buying public moves on, the world is left with dated artifacts that (at best) might lend their quirky charm to a time capsule buried in a school yard. In the case of Body Glove, however, it was the genuine dreams, passions and shared experiences of the Meistrell brothers that made their brand an enduring household name—not only for what it represents but also for the innovations and inroads that their company has made in the realms of surfing, diving and, ultimately, improving the world in which those activities take place.

According to Bob Meistrell, “People don’t work for me—they work with me.” Truer words are scarcely ever spoken, which is perhaps why the evolution of the Body Glove empire is so textured indeed.

When Bill Meistrell passed away in 2006 after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease, he left behind a familial and entrepreneurial legacy that continues to unfold almost as though he is still actively part of it. Both he and Bob founded Body Glove in 1953, inventing the first practical wetsuit while working as lifeguards and running their store, Dive N’ Surf, a South Bay institution even to this day.

Originally from Boonville, Missouri, the twins had moved to California with their widowed mother and five siblings to begin a new life in the wake of great tragedy. It’s the sort of American success story that is certifiably archetypal, until you begin to peel back the layers and discover the nuances that speak so uniquely of the Meistrell clan.

Bill Meistrell was born on July 30, 1928, followed by Bob 20 minutes later on July 31. It’s ironic that two twins who would “mirror” one another their entire lives, as Bob puts it, would not be born on the same day. But such are the fickle ways of fate.

Their life-long love of the water and shared athleticism was instilled in them at an early age at the recommendation of the family chiropractor. After caring for them during an early bout with pneumonia, he advised their mother to introduce them to swimming for its low-impact and overall composition-strengthening benefits.

Summers spent cleaning the local pool earned them coveted season passes and also enabled the boys to discover a passion for diving that culminated in the manufacturing of their own diving equipment for use at the local pond. Using an oilcan for a helmet and a bicycle pump attached to a garden hose for air, Bob admitted it was nothing short of a miracle that they didn’t die breathing the pressurized but poorly regulated air that was the best they could provide themselves with at that point in time.

Summers spent cleaning the local pool earned them coveted season passes and also enabled the boys to discover a passion for diving that culminated in the manufacturing of their own diving equipment for use at the local pond. Using an oilcan for a helmet and a bicycle pump attached to a garden hose for air, Bob admitted it was nothing short of a miracle that they didn’t die breathing the pressurized but poorly regulated air that was the best they could provide themselves with at that point in time.

Ingenuity and fearlessness were traits that exhibited themselves in both brothers early on, and upon learning this I quickly found myself pondering the question of nature, nurture and which of those two forces has the greatest influence on our lives. I am often wont to conclude that it is both, in equal measure, but my conversation with Bob imparted to me a sense of the role that active choices, made on a daily basis, have in synthesizing those two elements and determining the quality of one’s existence.

As I would soon learn, Bill’s and Bob’s adventure-filled afternoons at the local pond were preceded by a particularly unfortunate event, speaking volumes about the foundation upon which their lives were built. Before I spoke with Bob in 2009, I had already read that their father was murdered when they were just 4 years of age. I encountered that information as a sad footnote in a fairly straightforward biographical piece, and Bob’s retelling of the incident was nearly just as straightforward.

Their father, as it turns out, was a very successful lender back in 1932, and he operated a lucrative business at a time in history when the Great Depression made financial success of any kind something of a rarity. In a classic case of a working relationship that goes from bad to worse, his former business partner shot him in the back of the head to avoid paying him money that he owed him, adding insult to injury as he dragged his lifeless body into a safe.

Time would eventually reveal to Bill and Bob how magnanimous a man their father had been, particularly in the myriad stories that appreciative recipients of his services would later retell. During our interview, Bob chose to highlight one story in particular that seems to reveal volumes about the very spirit that drives his business even to this day.

Upon lending a certain gentleman $500, which Bob pointed out was a significant sum in the early 1930s, the gentleman inquired as to why he was not being handed a written agreement that would legally bind him to paying that amount back. The elder Meistrell’s reply to that question was a simple one: “I’m not asking you to sign anything because I know you are going to pay me back, since I am the only person in this town who will lend you that money in the first place.”

The recipient of the loan did pay him back, after going on to build a business that grew and supported him for many years. Similar displays of sheer confidence wind their way throughout the story of the Meistrell brothers and the unfolding of their businesses. This indicates that perhaps the family possesses a natural inner fortitude that is perpetrated by each generation’s examples to the next.

In the aftermath of their father’s death, Bill and Bob’s mother picked up where her husband left off, making ends meet by doing the best she could to collect the money people owed them. Her efforts were temporarily intercepted by a second husband who robbed the family of nearly everything they had.

In the aftermath of their father’s death, Bill and Bob’s mother picked up where her husband left off, making ends meet by doing the best she could to collect the money people owed them. Her efforts were temporarily intercepted by a second husband who robbed the family of nearly everything they had.

I didn’t even press Bob for the details of that little drama, because in the context of Bob’s discourse with me, they appeared to be just that—little. By this time the brothers were 16 years old and poised to begin the next phase of all of their lives.

Along with their mother and all five of their siblings, they moved to California, in no small part at the behest of their mother who, like her children, was not inclined to remain stationary in the waters that were now flowing so quickly under the bridge. What transpired in the years that followed is what you can read about in the history books, although in doing so one might incorrectly conclude that founding, growing and sustaining a multi-million dollar business requires only a few good ideas and some gumption.

The analogy that immediately comes to my mind is the experience of watching figure skaters on television—their grace is such that their movements appear almost easy, inspiring you to believe that if you decided to hit the rink the next day, you could simply and quickly replicate their movements. Such is the illusion.

It should be stated at this point in the story that Bill and Bob had three boyhood goals (all of them achieved, by the way): to own a submarine, to go deep-sea diving and to go treasure hunting. Once they began making wetsuits, they added a few more goals to that list. They were as follows: to never live more than five miles from work; to make “a little money”; to have fun; to make a great product; and to service it.

In other words, they never intended to make history or, for that matter, to build a worldwide business. Therein, stated Bob, is the secret of their success, which is defined by happiness and a satisfaction with life that cannot be bought. Bob received confirmation that he was succeeding in communicating this to the younger generation when, after giving a talk at Anaheim University, a young man in the audience came up to him to said that having fun in his work, not chasing dollars, would now become his goal.

Bob pointed out to me during our interview that he and Bill did not invent the wetsuit; a man by the name of Hugh Bradner did. They simply improved upon it and made it a relevant piece of gear for surfers instead of just divers.

After moving to California, the brothers quickly picked up surfing, playing football and swimming while attending Redondo Union and then El Segundo High School. They soon became acquainted with the surprisingly cold currents that flow down the coast of this state so known for its warm weather.

They were among the first surfers to add fiberglass to the noses of their surfboards for protection, and during these years Bill sold legendary surfer Greg Noll his first surfboard. The only time the brothers were ever separated from one another was when they were drafted into the Army, with Bill being sent to fight in Korea while Bob was stationed in Monterey.

When Bill returned from Korea in 1953, they bought into Dive N’ Surf, which was owned by their friend Bev Morgan. Their mother lent them $1,800 for this endeavor, which only generated $.15 from a magazine sale on their first day of business.

When Bill returned from Korea in 1953, they bought into Dive N’ Surf, which was owned by their friend Bev Morgan. Their mother lent them $1,800 for this endeavor, which only generated $.15 from a magazine sale on their first day of business.

They soon determined that selling $100 worth of merchandise per day would enable them to build a comfortably running business. For several years they had to lifeguard on the side to survive as they worked toward achieving that goal.

It was during this period that they developed relationships with such legendary watermen as surfers Bing Copeland, Rick Stoner, Dale Velzy, Hap Jacobs and Dewey Weber, all of whom shared with the Meistrell brothers a belief that surfing could one day become a highly-regarded sport. They began building wetsuits, ingeniously discovering that lining the insides of wetsuits with neoprene (a substance found on the backs of refrigerators) enabled the body to better retain heat.

Soon after, Bill would venture to the town of Bedford, Virginia and, after visiting a company by the name of Rubitek, happen upon a soft and stretchy fabric that was used to manufacture the Pontiac station wagon’s taillight gaskets. Surfing would never be the same again, as the brothers would soon begin making wetsuits with this fabric since it allowed for far more movement than the stiff wetsuits traditionally worn by divers.

When Bill told their marketing consultant Dick Boyd “it fits like a glove,” the name Body Glove was born. The brothers paid a mere $35 for a hand-drawn sketch of the logo that is now world-famous. Bob pointed out that when he and Bill were inducted into the Surfing Hall of Fame in 1990, it was not because they were among the best surfers the world had ever known but because they improved upon a technology that prevents surfers from drowning, in addition to keeping them warm so they can spend hours (instead of just minutes) in the water.

Ever the true watermen to the core and well-respected to boot, Bill and Bob were asked to serve as consultants for the television drama Sea Hunt starring actor Lloyd Bridges. The program debuted in 1958, one year after they bought Bev Morgan out of his portion of Dive N’ Surf.

After watching the pilot, Bob told the producers that it could become one of the biggest shows in the world, but that it also exhibited a lot of technical mistakes that threatened its authenticity. During the program’s highly successful three-year run, Bill and Bob built Lloyd Bridges’ diving suits and, unbeknownst to many at the time, actually taught him to dive.

Bob informed me that at first Lloyd’s diving scenes were performed by a stunt double. In his off-time, Lloyd would find excuses to avoid people’s invitations to join them on dives. Once the brothers taught him to dive, he performed all of his own stunts and even entrusted his entire family to Bill’s and Bob’s instruction.

The Meistrells would eventually teach such stars as Gary Cooper, Charlton Heston, Hugh O’Brian and Jill St. John to dive as well, befriending these stars while continuing to hone their product and joining the Hollywood scene only peripherally.

Although their businesses have grown steadily and strongly since their inceptions, the brothers did encounter setbacks over the years that Bob referred to as learning experiences and not failures. Among them was a decision to create wetsuits in an array of colors, which almost drove them into bankruptcy because the dye degraded the foam. One would imagine it would be nearly impossible to avoid all such occurrences when breaking technological ground, but perhaps it is even more difficult to maintain the strength of vision and composure that enables one to press on and flourish when such setbacks occur.

One of Body Glove’s taglines over the years has been “protect the core,” and it seems that the Meistrell family has done this both literally (with wetsuits that do just that) and figuratively. The business is still very much family-run, with Bill’s son Bill, Jr. serving as vice president and Bob’s son Robbie serving as CEO.

As Bill, Jr. was quick to point out to me, most family-run businesses do not survive the first generation. The Meistrells are now entering their third generation of family ownership of both Dive N’ Surf and Body Glove, and he believes it is because they continue to base their decisions on the foundation that Bill and Bob built.

As Bill, Jr. was quick to point out to me, most family-run businesses do not survive the first generation. The Meistrells are now entering their third generation of family ownership of both Dive N’ Surf and Body Glove, and he believes it is because they continue to base their decisions on the foundation that Bill and Bob built.

The fact that Bill and Bob actually fought like an old married couple on a regular basis is beside the point, since a spirit of mutual respect that transcended their differences regularly diffused their arguments. Bill preferred avoiding interviews in favor of building wetsuits in the back of the store, while Bob thrived on organization and interacting with the public. They realized, however, that their different preferences in regards to growing the businesses were completely necessary for their survival—and that very thought process governs their working relationships today.

Also governing the direction of the business is a people-first, grassroots approach to growth that is intimate and hands-on. It is probably for this reason that the city of Redondo Beach declared that October 1, 2006 would be Bill Meistrell Day after he passed. That’s how familiar this family is to the South Bay and Southern California at large.

Rather than investing millions of dollars in advertising the way some companies do, Body Glove opts to spend those dollars on its employees in exchange for a guerrilla approach to marketing that has proven highly successful.

The Body Glove logo continues to be highly recognized, in no small part because Bob’s son Ronnie regularly drives the Body Glove bus all over the country. On these trips he visits all of the stores that carry Body Glove products, forging stronger relationships with shop owners and introducing himself to potential customers along the way.

Bill, Jr.’s daughter Jenna is the first member of the family to graduate from college with a degree in business and a minor in communications. According to her father, she is also an expert communicator and a certified diving instructor like her great uncle, Bob.

Also in the people-come-first vein, the family places a very high premium on philanthropy and giving back to the community. Bob raised approximately $150,000 for charity annually for numerous organizations, offering catered day trips on the Body Glove boat in which he provided the crew, gas and other various aspects of his expertise as a local and a waterman.

He helped raise $22,000 for a replacement of the George Freeth statue that was stolen from the Redondo Beach Pier. He galvanized the collection of scrap metal with which to help create a new one and even offered a $5,000 reward for the return of the original. The original, decades-old mold was located, and this iconic piece of South Bay art commemorating the father of modern surfing was restored to its rightful place in the city.

As the hours passed during my 2009 meeting with Bob at his home and twilight began to descend, I felt compelled to ask him a potentially weighty question. Specifically, I wanted to know when Bob felt most in awe of the sea. Surely in all his years traversing the globe, he must have had moments of awe.

As the hours passed during my 2009 meeting with Bob at his home and twilight began to descend, I felt compelled to ask him a potentially weighty question. Specifically, I wanted to know when Bob felt most in awe of the sea. Surely in all his years traversing the globe, he must have had moments of awe.

What ensued was a tangent that took the better part of an hour, culminating with a tour of his extensive seashell collection and an introduction to two Chinese stone anchors that he found off the coast of Catalina that date back to 4,000 B.C. He spoke to me of encountering a lobster bullring during mating season, when he witnessed two bulls surrounded by upwards of 40 female lobsters.

And then, of course, there was the time that a 20-foot-long great white shark soared over him as he lay flat against the surface of a rock under seven feet of water. I was also somewhat blown away when he told me about the 226-pound, six-foot-long sea bass that once dragged him through the water after he speared it, which inspired him to call for a moratorium on the sport after a fishing club followed his example and decided to take out an entire herd in one weekend.

What I realized from these anecdotes is something about Bob that I had already learned: Experiences that some people would be thoroughly intimidated by are considered integral aspects of his life story. I also learned that Bob ultimately favored a harmonious approach to coexisting with nature, in which hunting never reaches the level of species decimation but occurs at educated intervals to promote balance in the ocean.

By our interview’s end, Bob kindly invited me to join his family for dinner, only after informing me that not two days later he would be leaving for a weeklong expedition to Mexico, where both he and Jenna would be diving with (you may have guessed it) sharks. They say youth is wasted on the young, but clearly that saying does not apply when you are Bob Meistrell and your years scarcely dimmed your light at all.

That light would go out on June 16, 2013, just off the coast of Catalina Island. A fittingly glorious summer day, Bob had set out on his 72-foot yacht, Disappearance. He was a young 84. Smooth sailing, Bob.

The Meistrell family and the birth of Body Glove.

[tribulant_slideshow gallery_id=”28″]