Viewers watch Jack Webb and Broderick Crawford play good cops on TV, but in reality Los Angeles police corruption is tantamount, and vice squads roam the dirty streets arresting gays, comedians and artists—with a cowboy vigilante mentality and off-kilter sense of morality. Unless they were bribed, of course.

To escape the heat, Angelinos take the Red Car to Abbot Kinney’s fantasy canal city by the sea, Venice, which has become so seedy that it doubles as a Mexican border town in Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil. Black oil derricks loom over the sand, and squalid beach shacks can be rented for $10 or $15 a month.

But the air and the light are better there. The luminosity is a product of intense sunlight refracted by droplets of mist and fog. That light (and the cheap rent) beckons artists who live in “pathetic poverty”—carousing, boozing and creating art that shocks, despite the derision of the art aristocracy that rules from Europe and New York City.

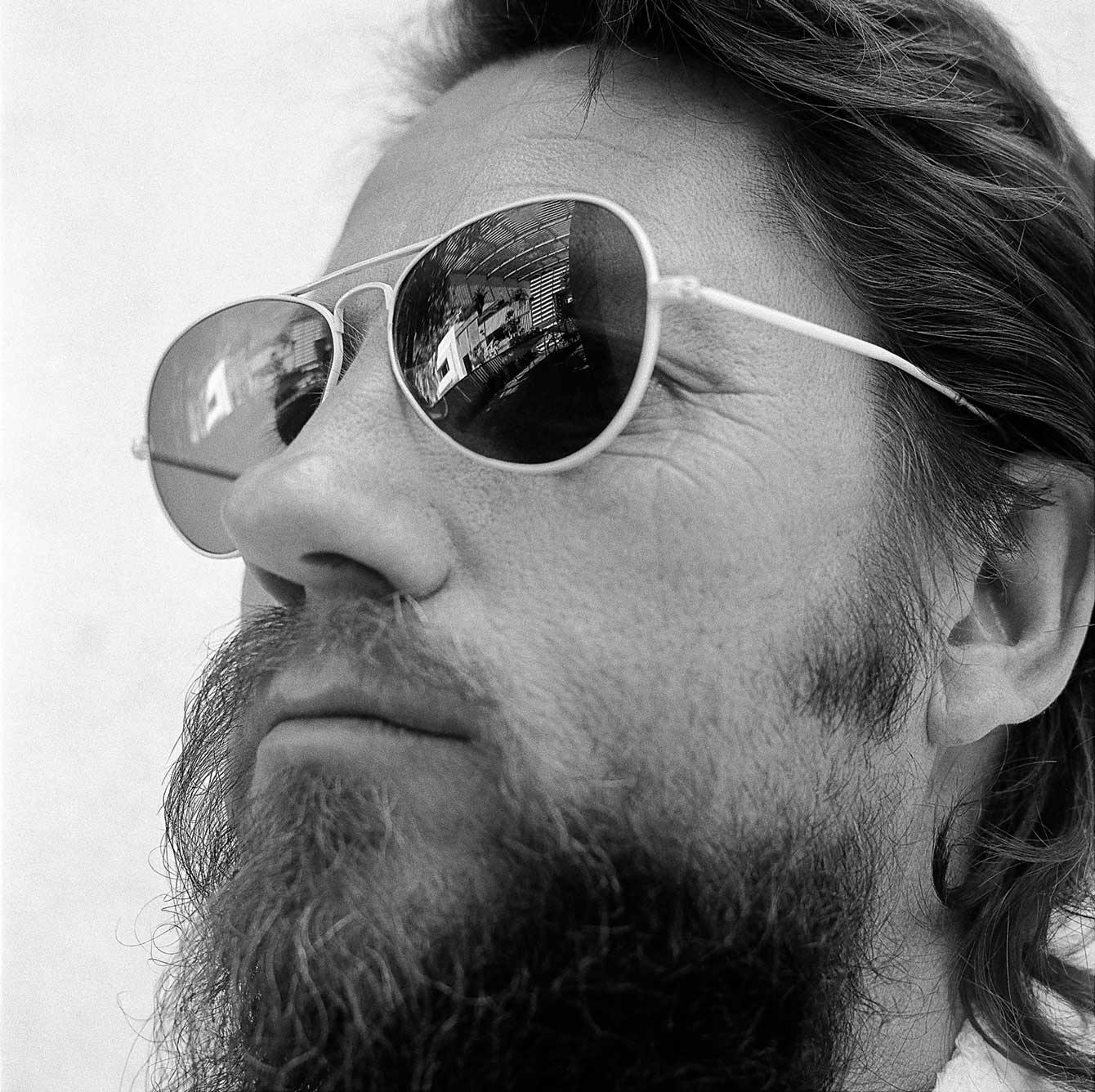

Against all odds, and with the support of one Los Angeles gallery and some brave collectors, these artists will finally find recognition decades later and put Los Angeles on the art world map. Ed Moses was one of those artists.

His long art career, which could be described as accidental, traversed some pretty rough terrain before he was recognized and celebrated as an icon of Los Angeles. His sons, nightclub king Cedd and painter Andy, have also contributed to the artistic and cultural fabric of the city.

Ed Moses’ family history contains few hints to explain his future life as an artist. His mother was born in 1900 in the tiny town of Laupāhoehoe in Hawaii, the daughter of a Portuguese man brought from the Azores by Queen Liliʻuokalani, who needed workers for her pineapple and sugarcane fields.

Ed’s father was of English/Welsh heritage and moved to Hawaii in 1900 from Nova Scotia to become a successful merchant and English teacher. His mother’s marriage to the older man was arranged, and Ed’s father bought his mother the first car on the Big Island.

The Depression took its toll on the family business, so they moved to San Pedro when Ed was an infant, returning to Hawaii when he was 2 after attempting to sell Kona coffee on the mainland with no success. His mother, after visiting her sister back in the U.S., picked up with a gambler briefly and eventually left his father for good, settling with little Ed in San Pedro.

Ed took up surfing in 1937, during his visits to see his father in Hawaii. The sport as we know it today was in its infancy, and the legendary Duke Kahanamoku gave Ed his first surfing lessons on Waikiki beach.

“The mahogany boards weighed 100 pounds in those days,” laughs Ed during an interview with his son Andy at his Venice house. “Eventually I could catch some swells, but that was the extent of it. A couple of times that board shot past my jaw … I guess I wanted to live.” He never surfed again after WWII, but Andy now surfs Southern California beaches regularly.

Ed served as a Navy surgical tech in the war and, after his discharge, entered Long Beach City College in 1946 as a pre-med student. In 1950, he moved to Venice. His first “shack” was on the Silver Strand (in pre-Marina Del Rey days), for which he paid $15 a month rent. He then transferred to UCLA.

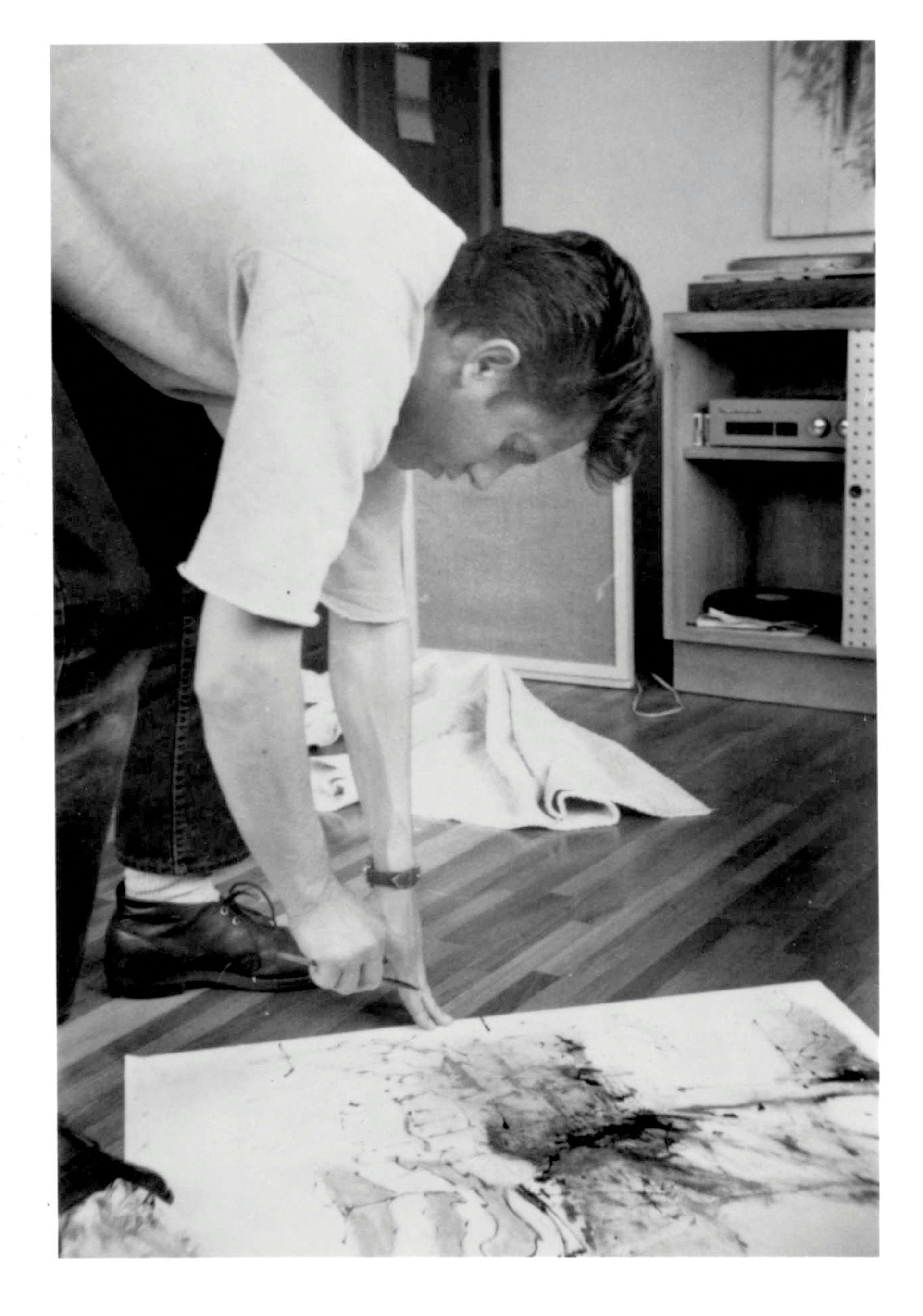

However, as is the case with many artists and performers, an encounter with a teacher provided the catalyst for a direction change in Ed’s life. Upon a friend’s suggestion, he had taken an elective art class taught by an eccentric art instructor, Pedro Miller.

“Our first assignment was to paint a still life,” Ed muses. “I didn’t know what the hell I was doing! I had never painted anything. Miller talked about Braque and Picasso, but most people at the time thought Norman Rockwell was art—and Miller hated Norman Rockwell. He had taught us how to mix paints with the right viscosity, and the other students were trying to render the still life. But I couldn’t draw, and I couldn’t paint.”

He continues, “Out of frustration, I dipped my hands in the paint inkwells and did this finger painting. Miller walked around the room, and he got closer and closer and finally he got to me. He looked at my painting and he looked at me, and he looked at my painting and he looked at me again. And he took my painting and put it up on a ridge that went around the room. All my friends looked over at me and laughed at it, but Pedro declared, ‘Now here’s a real artist.’ That was the beginning of the end of my life. Everybody started following me around as being the genius guy!”

From that moment on, Ed knew his destiny was set. Much to the chagrin of both parents, he changed majors from medicine to art. Soon he was carousing and rebelling with a small band of artists who had been drawn to Venice Beach by cheap rent and that light. The often-contentious group included Ed Keinholtz, Ed Ruscha, Craig Kauffman, Wallace Berman and Robert Irwin.

Ed’s graduate thesis was an exhibition at Ferus Gallery, a small space on La Cienega Boulevard that was started by Walter Hopps, a quiet man who loved the non-traditional art being produced by the group and wanted to bring it to the world art arena. According to the excellent documentary The Cool School (Arthouse Films) directed by Morgan Neville, the early days at Ferus Gallery were as much about the parties than the art.

Walter Hopps was not a particularly good businessman, and it wasn’t until the über-charming Irving Blum became his partner that the public started to take notice of the often-irreverent installations and abstract expressionism that could be found at the gallery. Ferus Gallery began to attract serious, wealthy collectors and Hollywood celebrity fans such as young actors Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper.

Suddenly, LA art was “hip,” and even New York City artists began to take notice. In fact, Andy Warhol first displayed Soup Cans at Ferus Gallery, and Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein also showed there.

Despite the camaraderie and bonding between the various artists who inhabited the scene, rivalries, career jealousy and brash opinions abounded. When asked about the beat poets who landed for a time in Venice, Ed Moses was forthright.

”Walter Hopps was a big fan of those guys, and so was Wally Berman,” Ed remembers. “Craig Kauffman and I thought they were clowns. Walter liked Wally Berman and thought he was like Marcel Duchamp, but Kauffman and I thought Wally was a clown too.”

Several of Ed’s influences while at UCLA were Willem de Kooning and Milton Resnick, “and the faculty hated all that.” They also were furious that he mounted his 1958 graduate thesis show at Ferus.

He was also inspired by Kauffman, a former architecture student who had transferred from USC and, despite his hatred of the UCLA art department, was well-known and considered to be “the fair-haired boy,” as Ed put it. “He was a snotty-nose prick, and we became friends.”

It’s no wonder the two hit it off. Ed was also a bad boy—challenging, irreverent, difficult. The UCLA art department wanted him out. But he and his artist friends were onto something, and collectors started to come around.

“In 1961, Hirshhorn came into my show at Ferus Gallery and wanted to buy the whole show. But I was a punk. Why should anyone have all my paintings? I told him I would only sell him three paintings. Irving and Walter were furious. At the time I thought it was a righteous decision. Later on I realized it was a stupid decision.”

Responding to the comment that son Andy has a comparatively polite demeanor, Ed claims, “He had a great mother. Very civilized.”

Ed married Avilda, a beauty originally from Virginia, in 1959—two weeks after meeting her at a kite-flying contest. In 1960, they produced Cedd, and Andy was born in 1962 during a mudslide that made getting to the hospital nearly impossible. The marriage (“like oil and water”) lasted 17 years.

“I was a terrible father,” admits Ed. His life was art, and he wanted nothing to get in the way. Having faced the ups and downs of a bohemian art lifestyle (“I didn’t really start selling paintings until the early 1970s”), he discouraged both sons from becoming artists. Cedd followed his advice, but Andy was as rebellious as his father and became an artist.

Few of the Venice artists ever ventured into downtown Los Angeles, despite a brief burst of art gallery activity in the 1960s (and another in the 1980s). “Nobody went downtown. There was nothing but winos down there. It wasn’t until Cedd established the cocktail scene down there that people started to go there,” says Ed with pride.

By the early 1960s, New York art dealers curiously ventured west to choose art to introduce to stuffy East Coast collectors. Although a show in New York of Billy Al Bengston’s work did not sell, it attracted the attention of New York artist Frank Stella, who eventually mounted a show at Ferus.

The influx of popular New York artists began to eat away at the core group of Venice artists who had been the mainstay of Ferus. Walter Hopps eventually left the gallery and moved on to the Pasadena Museum of Art, curating Marcel Duchamp’s first retrospective to much acclaim.

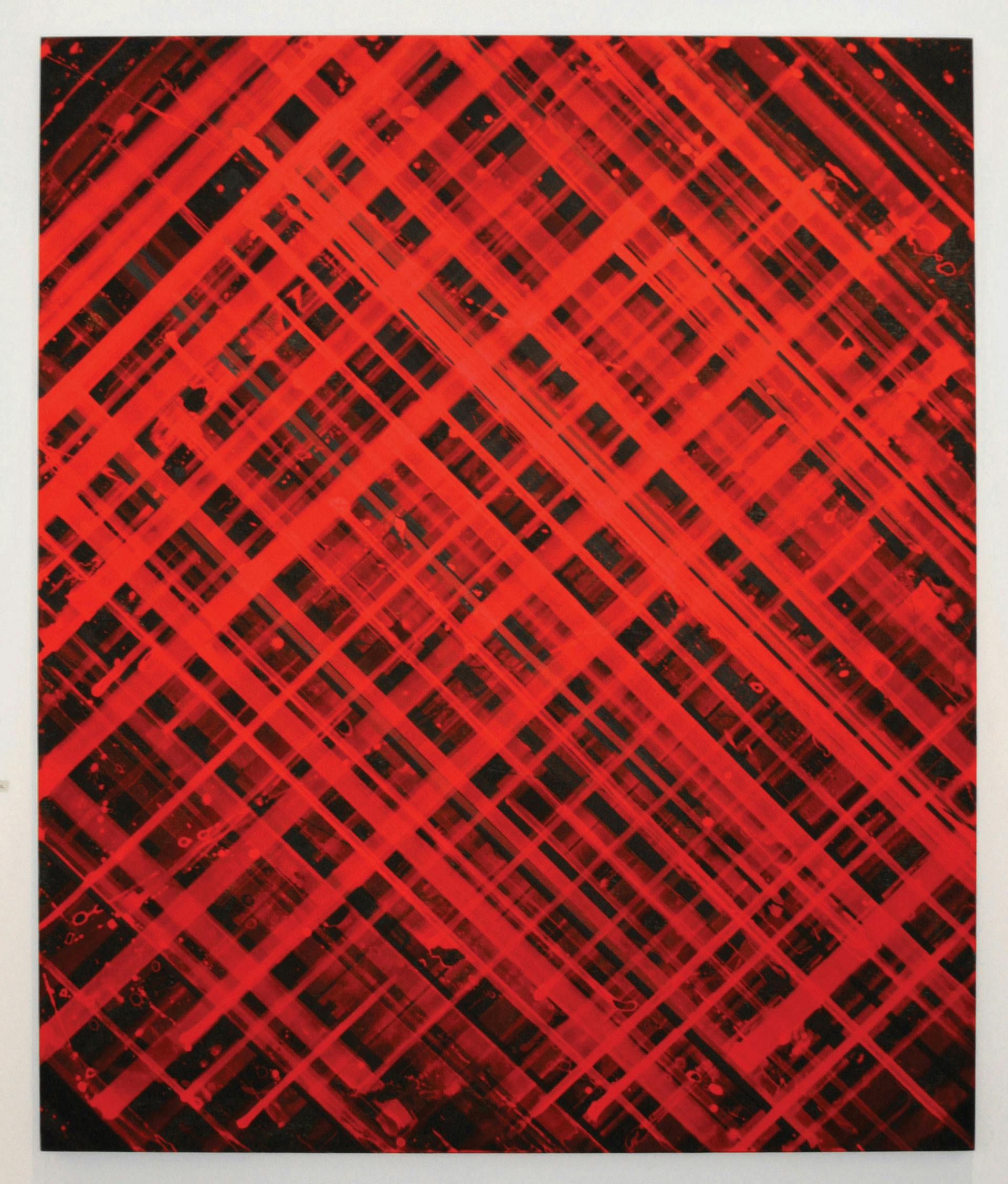

Ed Moses and the other Venice artists also began to show their work on the East Coast and today are internationally recognized for their groundbreaking contributions to the art world. Ed’s early linear, geometric art influenced several generations of abstract artists.

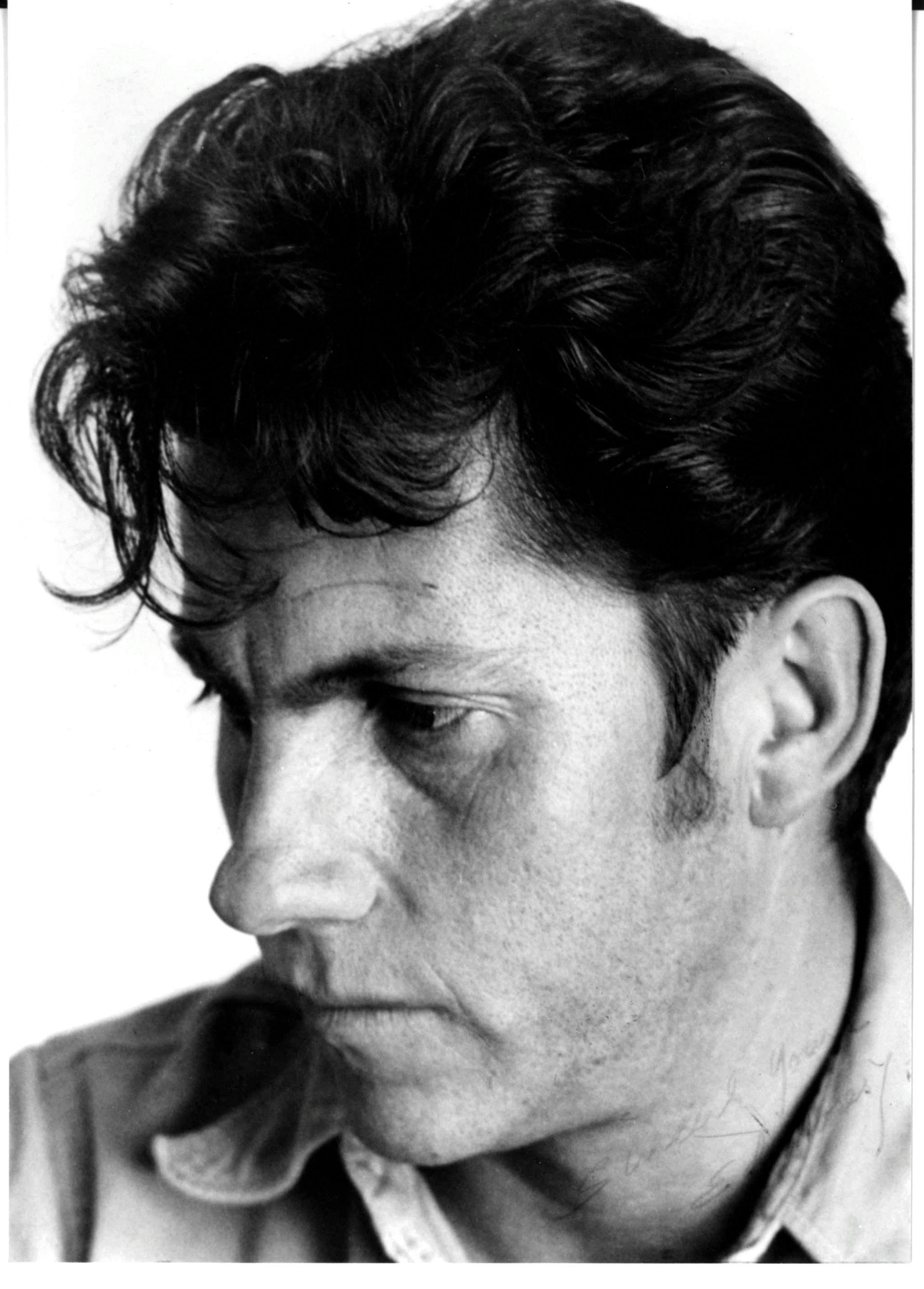

Interestingly, although Ed never had an interest in representational art, his son Andy’s work, although abstract, evokes the natural world to the viewer. Andy went to CalArts as a film student but migrated to art at the school, where his father’s artist friend John Baldessari was an instructor. True to his genes, Andy caused controversy at the school.

“One of my projects was called Father Knows Best, and it was a slap-dash effort that was a rip-off my father’s work. At the opening I tore it all up.”

Andy had been derided at Cal Arts. “It was always, ‘Ed’s son, he’s just Ed’s son.’” But after that show, he found new admiration. Conceptual art was flourishing, and his show fit the bill.

He left Cal Arts after two years, crucially aware that he couldn’t grow as a painter at the school. Andy went to New York to find his own way in the early 1980s, an exciting and fast-moving time in that city’s art scene. He started showing in New York, Italy and Los Angeles in the late 1980s but eventually came back to LA to throw his hat in the filmmaking ring.

Becoming disillusioned by the constant meetings and dead ends, he moved to Malibu and returned to art, creating iridescent paintings influenced by his love of surfing and the landscapes. “I have always been inspired by nature—not John Muir nature but the moving, fluid dynamics of the natural world,” says Andy.

Ironically, Cedd adores the very downtown LA core that his father loathed. He has revitalized and rehabilitated derelict venues such as the Broadway Bar, Seven Grand, Golden Gopher and Cole’s into vintage-flavored popular nightclubs that retain the feel but not the grit of the inner city.

“My dad told me not to become an artist. He said it is a tough and painful career,” says Cedd. I decided to move into business and support artists. I began my first business at 12 years old. It came from being the older brother and knowing I needed to be the provider since everyone else was an artist. I have always collected art and now run a nonprofit, supporting and documenting art.”

Cedd also served as executive producer for the documentary The Cool School about Ferus Gallery. He sees the potential for LA to be a major metropolitan city. “For LA to grow is to grow up. It needs a high-density center with great mass transit, cultural institutions and nonstop energy.”

He knows that business is a great creative outlet. “Andy Warhol once said that business is an art form. The growth of a creative business is an organic process that has so many nuances and extrapolations.”

Patriarch Ed continues to create art that inspires and provokes in his beautiful Venice studio/residence. One cannot help but notice the twinkle in his curmudgeonly eyes when he speaks of his recent show at Frank Lloyd Gallery in Santa Monica. “Some of my best friends won’t even talk to me. They hated it.”

How painter Ed Moses and a raucous band of young artists electrified the Los Angeles art scene.

Los Angeles in the 1950s. This is the city.

The sunshine that drew millions of WWII veterans and fame-seeking starlets is beginning to dim from the smog wafting up from the car-choked streets. The once-glamorous movie and theatre palaces on Broadway Street are losing their audiences to a new gadget with a spacey name: television.

Viewers watch Jack Webb and Broderick Crawford play good cops on TV, but in reality Los Angeles police corruption is tantamount, and vice squads roam the dirty streets arresting gays, comedians and artists—with a cowboy vigilante mentality and off-kilter sense of morality. Unless they were bribed, of course.

To escape the heat, Angelinos take the Red Car to Abbot Kinney’s fantasy canal city by the sea, Venice, which has become so seedy that it doubles as a Mexican border town in Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil. Black oil derricks loom over the sand, and squalid beach shacks can be rented for $10 or $15 a month.

But the air and the light are better there. The luminosity is a product of intense sunlight refracted by droplets of mist and fog. That light (and the cheap rent) beckons artists who live in “pathetic poverty”—carousing, boozing and creating art that shocks, despite the derision of the art aristocracy that rules from Europe and New York City.

Against all odds, and with the support of one Los Angeles gallery and some brave collectors, these artists will finally find recognition decades later and put Los Angeles on the art world map. Ed Moses was one of those artists.

His long art career, which could be described as accidental, traversed some pretty rough terrain before he was recognized and celebrated as an icon of Los Angeles. His sons, nightclub king Cedd and painter Andy, have also contributed to the artistic and cultural fabric of the city.

Ed Moses’ family history contains few hints to explain his future life as an artist. His mother was born in 1900 in the tiny town of Laupāhoehoe in Hawaii, the daughter of a Portuguese man brought from the Azores by Queen Liliʻuokalani, who needed workers for her pineapple and sugarcane fields.

Ed’s father was of English/Welsh heritage and moved to Hawaii in 1900 from Nova Scotia to become a successful merchant and English teacher. His mother’s marriage to the older man was arranged, and Ed’s father bought his mother the first car on the Big Island.

The Depression took its toll on the family business, so they moved to San Pedro when Ed was an infant, returning to Hawaii when he was 2 after attempting to sell Kona coffee on the mainland with no success. His mother, after visiting her sister back in the U.S., picked up with a gambler briefly and eventually left his father for good, settling with little Ed in San Pedro.

Ed took up surfing in 1937, during his visits to see his father in Hawaii. The sport as we know it today was in its infancy, and the legendary Duke Kahanamoku gave Ed his first surfing lessons on Waikiki beach.

“The mahogany boards weighed 100 pounds in those days,” laughs Ed during an interview with his son Andy at his Venice house. “Eventually I could catch some swells, but that was the extent of it. A couple of times that board shot past my jaw … I guess I wanted to live.” He never surfed again after WWII, but Andy now surfs Southern California beaches regularly.

Ed served as a Navy surgical tech in the war and, after his discharge, entered Long Beach City College in 1946 as a pre-med student. In 1950, he moved to Venice. His first “shack” was on the Silver Strand (in pre-Marina Del Rey days), for which he paid $15 a month rent. He then transferred to UCLA.

However, as is the case with many artists and performers, an encounter with a teacher provided the catalyst for a direction change in Ed’s life. Upon a friend’s suggestion, he had taken an elective art class taught by an eccentric art instructor, Pedro Miller.

“Our first assignment was to paint a still life,” Ed muses. “I didn’t know what the hell I was doing! I had never painted anything. Miller talked about Braque and Picasso, but most people at the time thought Norman Rockwell was art—and Miller hated Norman Rockwell. He had taught us how to mix paints with the right viscosity, and the other students were trying to render the still life. But I couldn’t draw, and I couldn’t paint.”

He continues, “Out of frustration, I dipped my hands in the paint inkwells and did this finger painting. Miller walked around the room, and he got closer and closer and finally he got to me. He looked at my painting and he looked at me, and he looked at my painting and he looked at me again. And he took my painting and put it up on a ridge that went around the room. All my friends looked over at me and laughed at it, but Pedro declared, ‘Now here’s a real artist.’ That was the beginning of the end of my life. Everybody started following me around as being the genius guy!”

From that moment on, Ed knew his destiny was set. Much to the chagrin of both parents, he changed majors from medicine to art. Soon he was carousing and rebelling with a small band of artists who had been drawn to Venice Beach by cheap rent and that light. The often-contentious group included Ed Keinholtz, Ed Ruscha, Craig Kauffman, Wallace Berman and Robert Irwin.

Ed’s graduate thesis was an exhibition at Ferus Gallery, a small space on La Cienega Boulevard that was started by Walter Hopps, a quiet man who loved the non-traditional art being produced by the group and wanted to bring it to the world art arena. According to the excellent documentary The Cool School (Arthouse Films) directed by Morgan Neville, the early days at Ferus Gallery were as much about the parties than the art.

Walter Hopps was not a particularly good businessman, and it wasn’t until the über-charming Irving Blum became his partner that the public started to take notice of the often-irreverent installations and abstract expressionism that could be found at the gallery. Ferus Gallery began to attract serious, wealthy collectors and Hollywood celebrity fans such as young actors Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper.

Suddenly, LA art was “hip,” and even New York City artists began to take notice. In fact, Andy Warhol first displayed Soup Cans at Ferus Gallery, and Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein also showed there.

Despite the camaraderie and bonding between the various artists who inhabited the scene, rivalries, career jealousy and brash opinions abounded. When asked about the beat poets who landed for a time in Venice, Ed Moses was forthright.

”Walter Hopps was a big fan of those guys, and so was Wally Berman,” Ed remembers. “Craig Kauffman and I thought they were clowns. Walter liked Wally Berman and thought he was like Marcel Duchamp, but Kauffman and I thought Wally was a clown too.”

Several of Ed’s influences while at UCLA were Willem de Kooning and Milton Resnick, “and the faculty hated all that.” They also were furious that he mounted his 1958 graduate thesis show at Ferus.

He was also inspired by Kauffman, a former architecture student who had transferred from USC and, despite his hatred of the UCLA art department, was well-known and considered to be “the fair-haired boy,” as Ed put it. “He was a snotty-nose prick, and we became friends.”

It’s no wonder the two hit it off. Ed was also a bad boy—challenging, irreverent, difficult. The UCLA art department wanted him out. But he and his artist friends were onto something, and collectors started to come around.

“In 1961, Hirshhorn came into my show at Ferus Gallery and wanted to buy the whole show. But I was a punk. Why should anyone have all my paintings? I told him I would only sell him three paintings. Irving and Walter were furious. At the time I thought it was a righteous decision. Later on I realized it was a stupid decision.”

Responding to the comment that son Andy has a comparatively polite demeanor, Ed claims, “He had a great mother. Very civilized.”

Ed married Avilda, a beauty originally from Virginia, in 1959—two weeks after meeting her at a kite-flying contest. In 1960, they produced Cedd, and Andy was born in 1962 during a mudslide that made getting to the hospital nearly impossible. The marriage (“like oil and water”) lasted 17 years.

“I was a terrible father,” admits Ed. His life was art, and he wanted nothing to get in the way. Having faced the ups and downs of a bohemian art lifestyle (“I didn’t really start selling paintings until the early 1970s”), he discouraged both sons from becoming artists. Cedd followed his advice, but Andy was as rebellious as his father and became an artist.

Few of the Venice artists ever ventured into downtown Los Angeles, despite a brief burst of art gallery activity in the 1960s (and another in the 1980s). “Nobody went downtown. There was nothing but winos down there. It wasn’t until Cedd established the cocktail scene down there that people started to go there,” says Ed with pride.

By the early 1960s, New York art dealers curiously ventured west to choose art to introduce to stuffy East Coast collectors. Although a show in New York of Billy Al Bengston’s work did not sell, it attracted the attention of New York artist Frank Stella, who eventually mounted a show at Ferus.

The influx of popular New York artists began to eat away at the core group of Venice artists who had been the mainstay of Ferus. Walter Hopps eventually left the gallery and moved on to the Pasadena Museum of Art, curating Marcel Duchamp’s first retrospective to much acclaim.

Ed Moses and the other Venice artists also began to show their work on the East Coast and today are internationally recognized for their groundbreaking contributions to the art world. Ed’s early linear, geometric art influenced several generations of abstract artists.

Interestingly, although Ed never had an interest in representational art, his son Andy’s work, although abstract, evokes the natural world to the viewer. Andy went to CalArts as a film student but migrated to art at the school, where his father’s artist friend John Baldessari was an instructor. True to his genes, Andy caused controversy at the school.

“One of my projects was called Father Knows Best, and it was a slap-dash effort that was a rip-off my father’s work. At the opening I tore it all up.”

Andy had been derided at Cal Arts. “It was always, ‘Ed’s son, he’s just Ed’s son.’” But after that show, he found new admiration. Conceptual art was flourishing, and his show fit the bill.

He left Cal Arts after two years, crucially aware that he couldn’t grow as a painter at the school. Andy went to New York to find his own way in the early 1980s, an exciting and fast-moving time in that city’s art scene. He started showing in New York, Italy and Los Angeles in the late 1980s but eventually came back to LA to throw his hat in the filmmaking ring.

Becoming disillusioned by the constant meetings and dead ends, he moved to Malibu and returned to art, creating iridescent paintings influenced by his love of surfing and the landscapes. “I have always been inspired by nature—not John Muir nature but the moving, fluid dynamics of the natural world,” says Andy.

Ironically, Cedd adores the very downtown LA core that his father loathed. He has revitalized and rehabilitated derelict venues such as the Broadway Bar, Seven Grand, Golden Gopher and Cole’s into vintage-flavored popular nightclubs that retain the feel but not the grit of the inner city.

“My dad told me not to become an artist. He said it is a tough and painful career,” says Cedd. I decided to move into business and support artists. I began my first business at 12 years old. It came from being the older brother and knowing I needed to be the provider since everyone else was an artist. I have always collected art and now run a nonprofit, supporting and documenting art.”

Cedd also served as executive producer for the documentary The Cool School about Ferus Gallery. He sees the potential for LA to be a major metropolitan city. “For LA to grow is to grow up. It needs a high-density center with great mass transit, cultural institutions and nonstop energy.”

He knows that business is a great creative outlet. “Andy Warhol once said that business is an art form. The growth of a creative business is an organic process that has so many nuances and extrapolations.”

Patriarch Ed continues to create art that inspires and provokes in his beautiful Venice studio/residence. One cannot help but notice the twinkle in his curmudgeonly eyes when he speaks of his recent show at Frank Lloyd Gallery in Santa Monica. “Some of my best friends won’t even talk to me. They hated it.”

How painter Ed Moses and a raucous band of young artists electrified the Los Angeles art scene.

[tribulant_slideshow gallery_id=”22″]