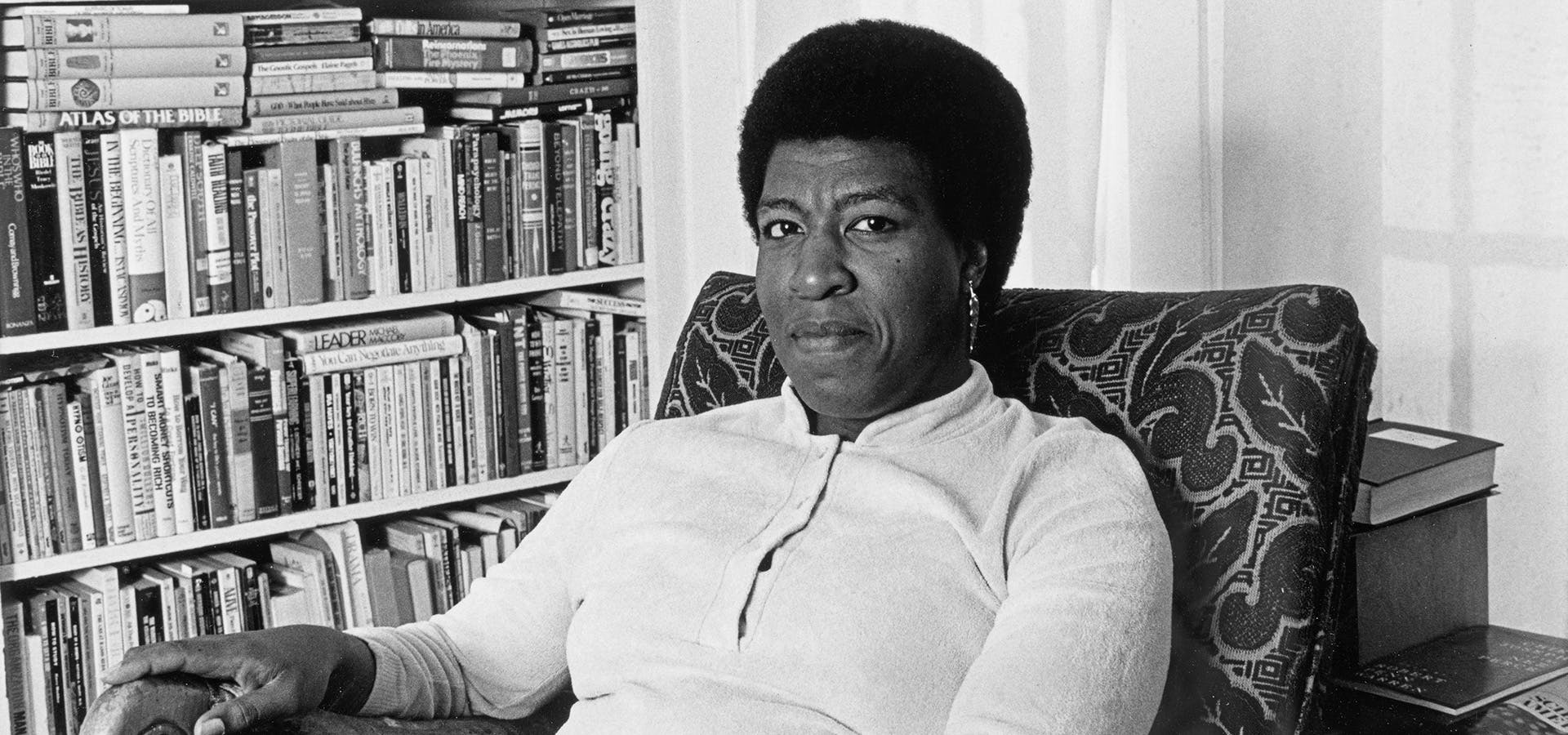

“She was a pioneer—a master storyteller who brought her voice, the voice of a woman of color, to science fiction,” said Natalie Russell, assistant curator of literary manuscripts at The Huntington and curator of the exhibition. “Tired of stories featuring white, male heroes, she developed an alternative narrative from a very personal point of view.”

A Pasadena native, Butler told the New York Times in a 2000 interview: “When I began writing science fiction, when I began reading, heck, I wasn’t in any of this stuff I read. The only black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn’t manage anything, anyway. I wrote myself in, since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing.”

Butler would have been 70 in 2017; she died an untimely death at age 58, apparently of a stroke at her home in Seattle.

“Octavia E. Butler: Telling My Stories” follows a roughly chronological thread and includes approximately 100 items that reveal the writer’s early years and influences, as well as highlight specific themes that repeatedly commanded her attention.

After Butler’s death, The Huntington became the recipient of her papers, which arrived in 2008 in two four-drawer file cabinets and 35 large cartons. “She kept nearly everything,” said Russell, “from her very first short stories, written at age 12, to book contracts and programs from speaking engagements. The body of materials includes 8,000 individual items and more than 80 boxes of additional items: extensive drafts, notes, and research materials for more than a dozen novels, numerous shorts stories and essays, as well as correspondence and other materials. By the time the collection had been processed and catalogued, more than 40 scholars were asking to get access to it. In the past two years, it has been used nearly 1,300 times—or roughly 15 times per week, said Russell, making it one of the most actively researched archives at The Huntington.

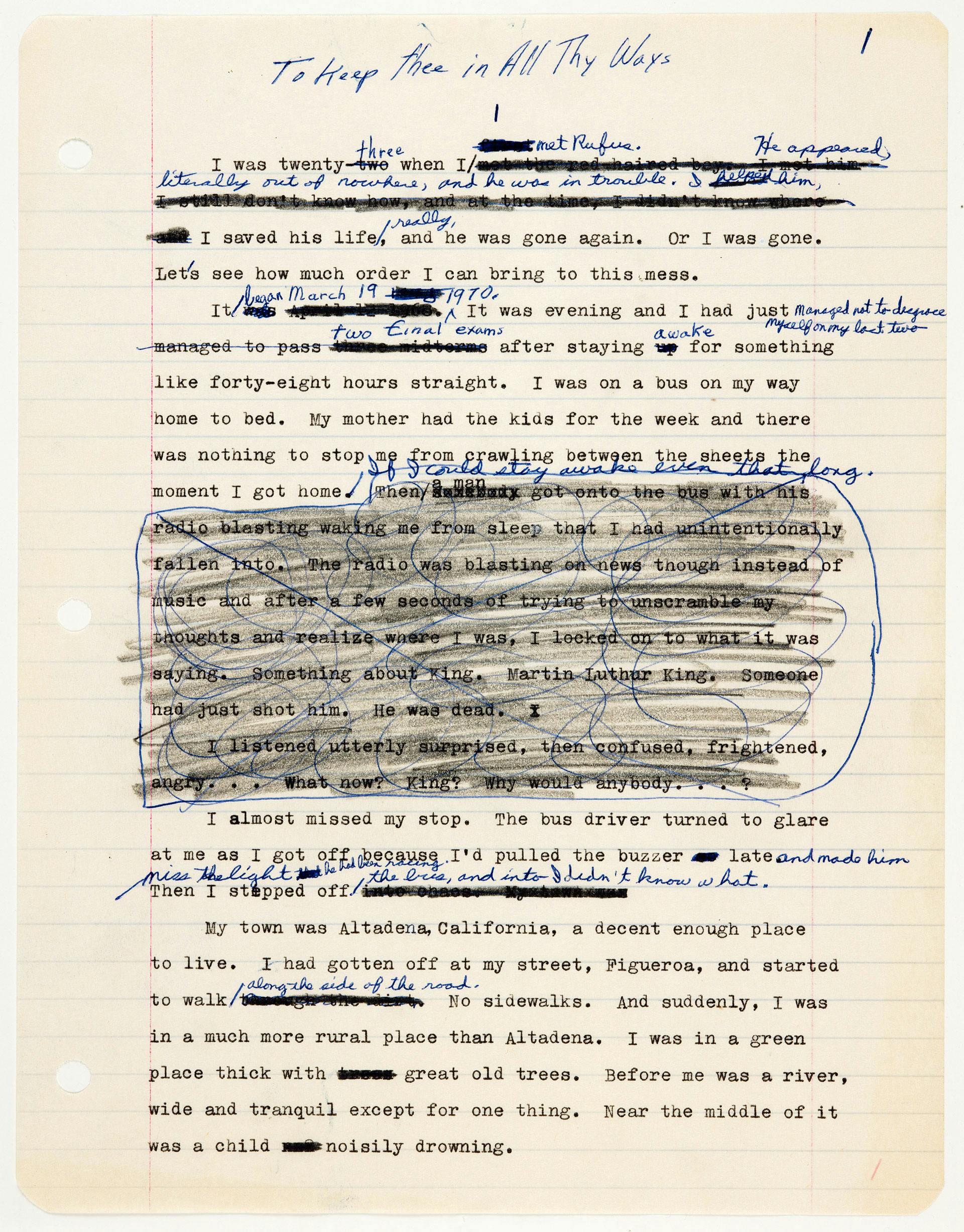

Butler was born June 22, 1947, to a maid and a shoeshine man. Her father died when she was quite young; an only child, she was raised primarily by her mother. “She discovered writing very early, in large part because, she said, it suited her shy nature, and it was permitted in her strict Baptist household,” said Russell. The exhibition will feature samples of her first stories.

But, says Russell, it was a 1954 science fiction film called Devil Girl from Mars that inspired Butler to take on science fiction. “She was convinced she could write a better story than the one unfolding on the screen,” Russell said.

Butler enrolled in every creative writing course she could find and was active in the Afro-relations club at Pasadena City College, an early indication of her interest in current events and Civil Rights issues. In the early 1970s, at a workshop for minority writers, she met the science fiction author Harlan Ellison, who introduced her to the Clarion Science Fiction Workshop, where Butler learned to hone her craft among other like-minded writers; it was then that she sold her first story. Following Clarion, she took odd jobs to support herself—even trying to establish her own laminating business, documents show; she wrote in the early morning hours before work.

But the road to success was long and slow. “In fact,” she once said, “I had five more years of rejection slips and horrible little jobs ahead of me before I sold another word.”

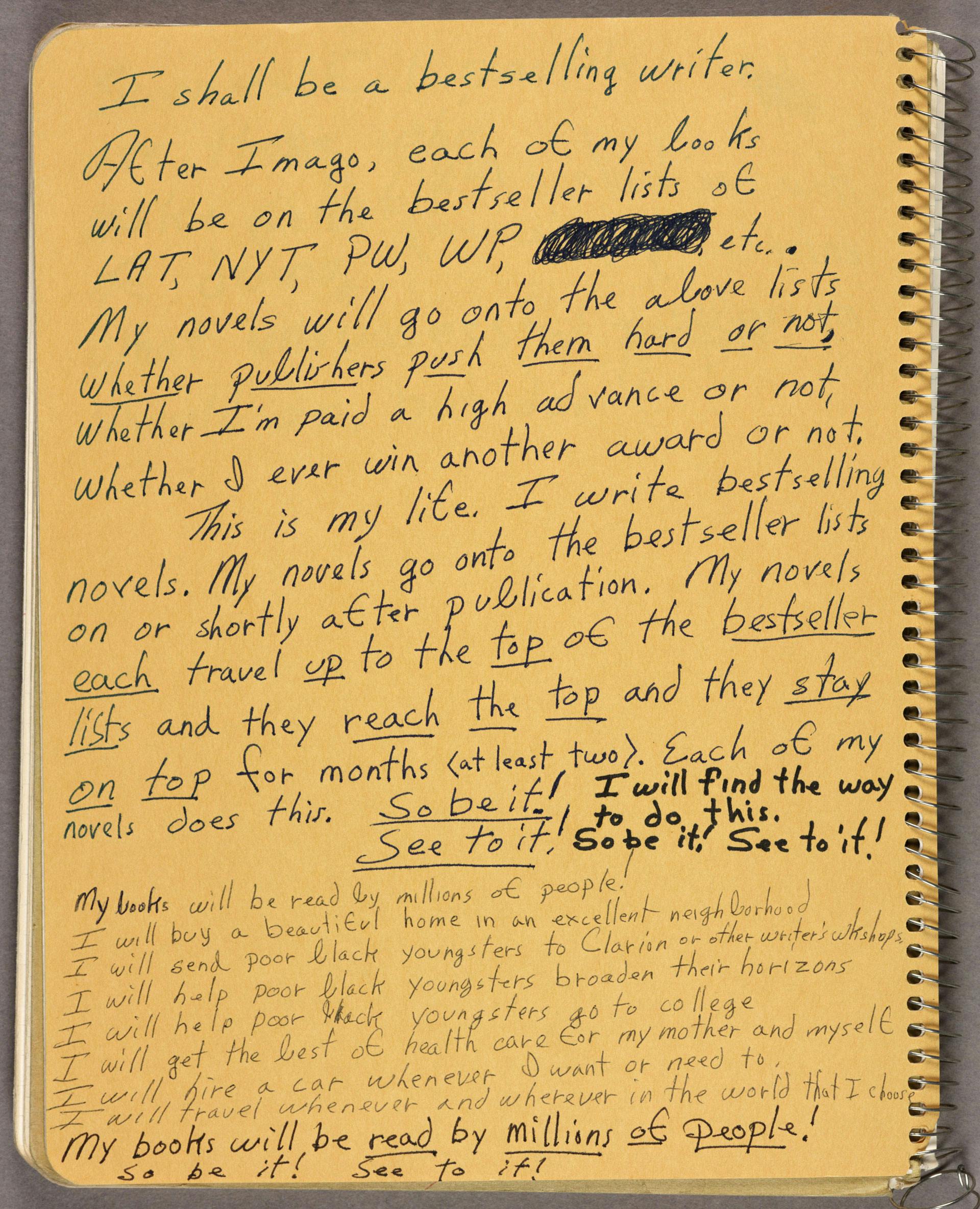

On display in the exhibition will be a page of motivational notes in which she writes, “I am a Bestselling Writer. I write Bestselling Books … Every day in every way I am researching and writing my award winning Bestselling Books and short stories … Every one of my books reaches and remains for two or more months at the top of the bestseller lists . . . So Be It! See To It.”

In 1975, she sold her first novel, Patternmaster, to Doubleday, quickly followed by Mind of My Mind and Survivor; the trio comprise part of her “Patternist” series, depicting the evolution of humanity into three distinct genetic groups. A review on display in the exhibition lauds Patternmaster for its especially well-constructed plot and progressive heroine, who is “a refreshing change of pace from the old days.”

And her following continued to grow.

By the late 1970s, Butler was able to make a living on her writing alone. She won her first Hugo award in 1985 for the short story “Speech Sounds,” followed by other awards, including a Locus and Nebula.

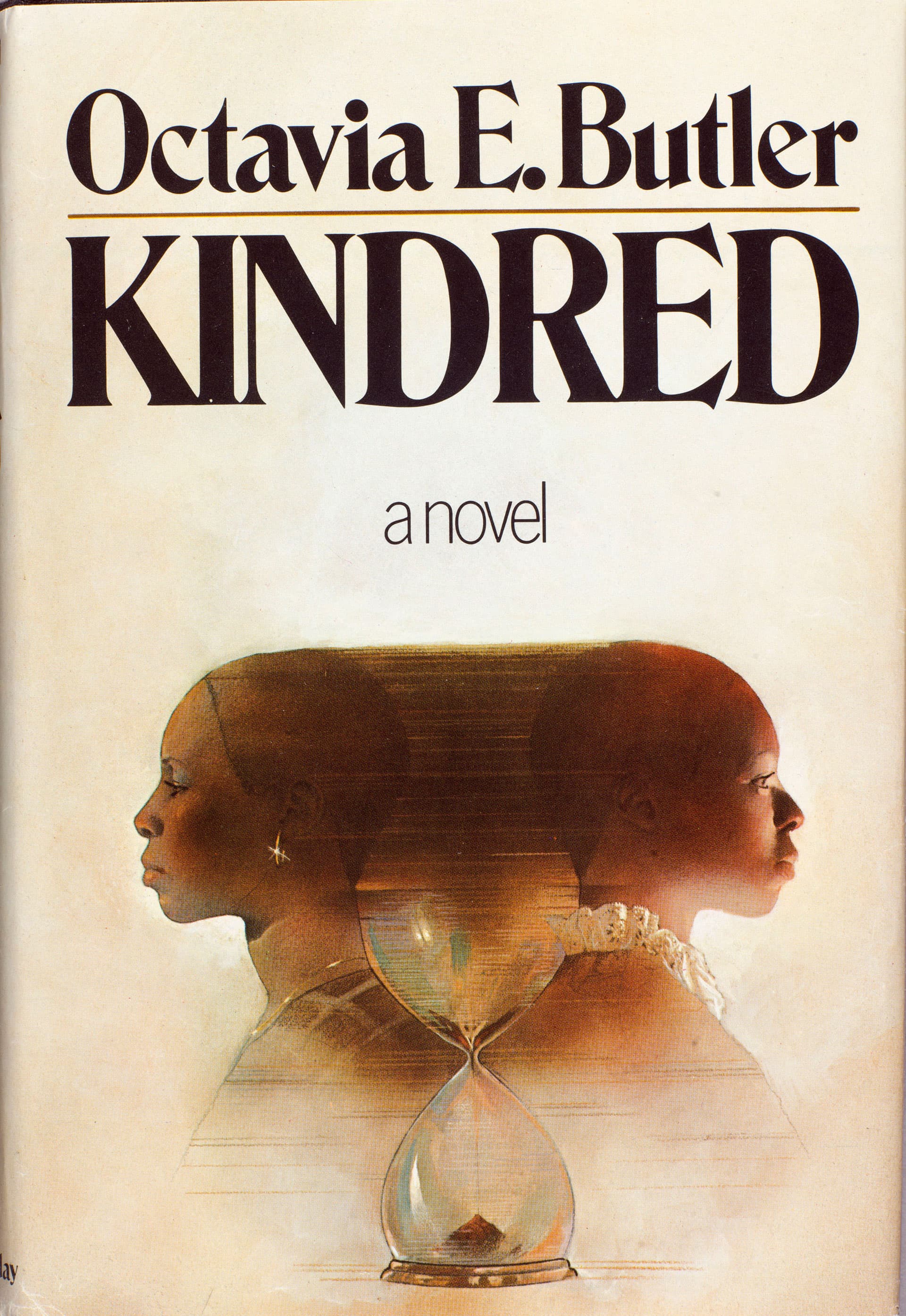

“Octavia E. Butler: Telling My Stories” will include examples of journal entries, photographs, and first editions of her books, including Kindred, arguably her best-known work. The book is less science fiction and more fantasy, involving an African-American woman who travels back in time to the horrors of plantation life in pre-Civil War Maryland. “I wanted to reach people emotionally in a way that history tends not to,” Butler said about the book. Published in 1979, Kindred continues to command widespread appeal and is regularly taught in high schools and at the university level, as well as chosen for community-wide reading programs and book clubs.

Beyond race, Butler explored tensions between the sexes and worked to develop strong female characters, a hallmark of her writing. “Being a woman in a male-dominated genre lent Butler’s stories a unique voice,” said Russell. “She would, for instance, depict women as resolving their problems through means other than violence—using flexibility, nurturing, and sensitivity instead.”

Butler once remarked, “Girls become women by giving life, and boys become men by taking it.” But she also challenged traditional gender identity, said Russell. Bloodchild, for example, is a story about a pregnant man, and in Wild Seed, the plot develops around two shape-shifting—and sex-changing—characters, Doro and Anyanwu. The exhibition includes notes Butler made about the two characters as she worked to develop them.

Butler sought to meticulously research the science in her fiction, traveling to the Amazon to get a firsthand look at extreme biological diversity in an effort to better incorporate biology, genetics, and medicine in her work. On display will be photographs from that research trip, as well as a small notebook of plant sketches. Climate change concerned her, as did politics, the pharmaceutical industry, and a variety of social issues, and as a result, she wove them all into her writing. “What’s striking,” said Russell, “is her ability to tease out and focus on issues that have had and likely will have currency for decades. She was amazingly prescient and given that, her stories resonate in very powerful ways today. Perhaps even more so than when they were first published.”

For more on the Butler exhibition, visit The Huntington website.

A new exhibition opening this spring at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens examines the life and work of celebrated author Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006), the first science fiction writer to receive a prestigious MacArthur “genius” award and the first African-American woman to win widespread recognition writing in that genre. “Octavia E. Butler: Telling My Stories” continues through Aug. 7 in the West Hall of the Library. Butler’s literary archive resides at The Huntington.

“She was a pioneer—a master storyteller who brought her voice, the voice of a woman of color, to science fiction,” said Natalie Russell, assistant curator of literary manuscripts at The Huntington and curator of the exhibition. “Tired of stories featuring white, male heroes, she developed an alternative narrative from a very personal point of view.”

A Pasadena native, Butler told the New York Times in a 2000 interview: “When I began writing science fiction, when I began reading, heck, I wasn’t in any of this stuff I read. The only black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn’t manage anything, anyway. I wrote myself in, since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing.”

Butler would have been 70 in 2017; she died an untimely death at age 58, apparently of a stroke at her home in Seattle.

“Octavia E. Butler: Telling My Stories” follows a roughly chronological thread and includes approximately 100 items that reveal the writer’s early years and influences, as well as highlight specific themes that repeatedly commanded her attention.

After Butler’s death, The Huntington became the recipient of her papers, which arrived in 2008 in two four-drawer file cabinets and 35 large cartons. “She kept nearly everything,” said Russell, “from her very first short stories, written at age 12, to book contracts and programs from speaking engagements. The body of materials includes 8,000 individual items and more than 80 boxes of additional items: extensive drafts, notes, and research materials for more than a dozen novels, numerous shorts stories and essays, as well as correspondence and other materials. By the time the collection had been processed and catalogued, more than 40 scholars were asking to get access to it. In the past two years, it has been used nearly 1,300 times—or roughly 15 times per week, said Russell, making it one of the most actively researched archives at The Huntington.

Butler was born June 22, 1947, to a maid and a shoeshine man. Her father died when she was quite young; an only child, she was raised primarily by her mother. “She discovered writing very early, in large part because, she said, it suited her shy nature, and it was permitted in her strict Baptist household,” said Russell. The exhibition will feature samples of her first stories.

But, says Russell, it was a 1954 science fiction film called Devil Girl from Mars that inspired Butler to take on science fiction. “She was convinced she could write a better story than the one unfolding on the screen,” Russell said.

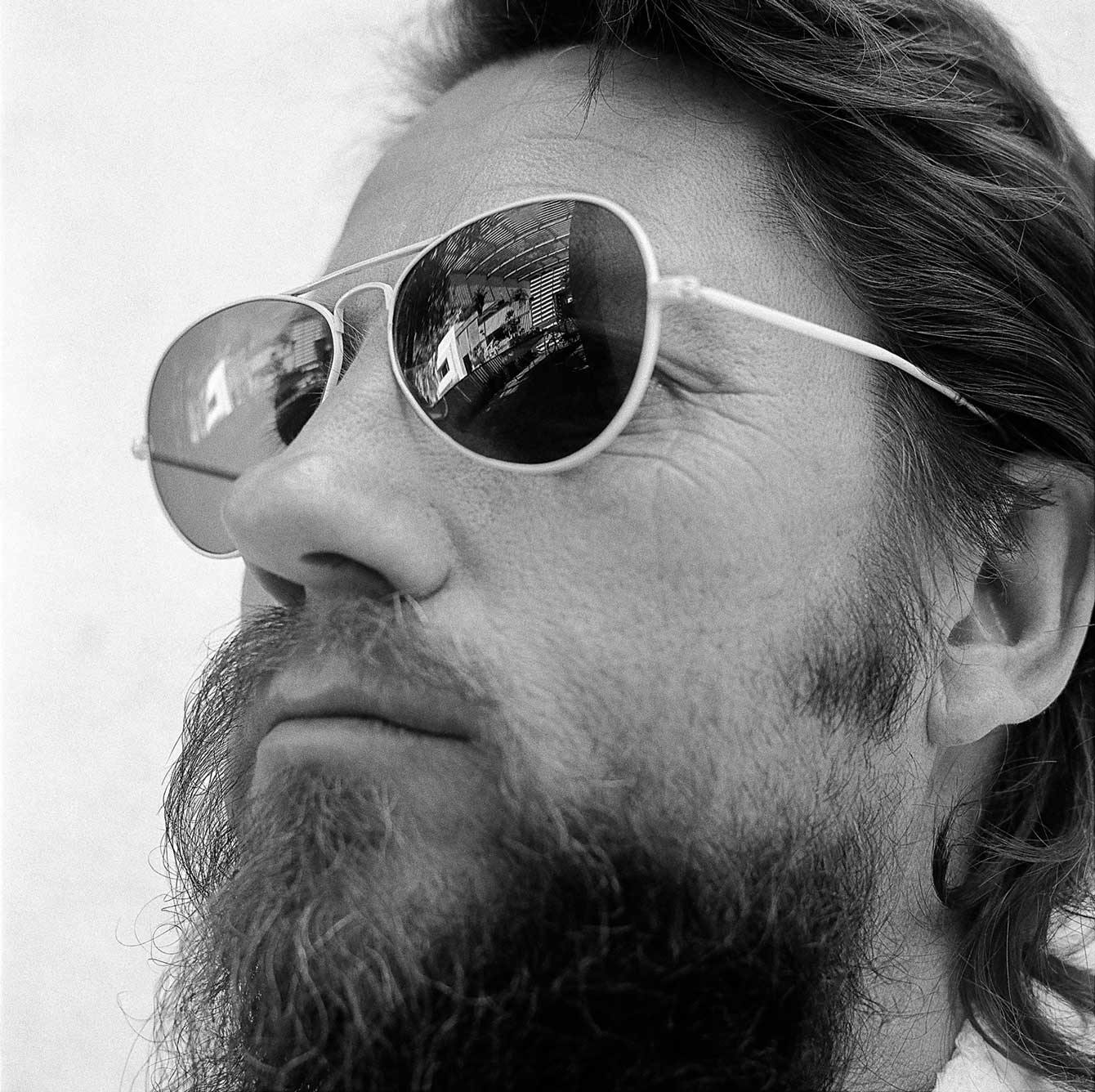

Butler enrolled in every creative writing course she could find and was active in the Afro-relations club at Pasadena City College, an early indication of her interest in current events and Civil Rights issues. In the early 1970s, at a workshop for minority writers, she met the science fiction author Harlan Ellison, who introduced her to the Clarion Science Fiction Workshop, where Butler learned to hone her craft among other like-minded writers; it was then that she sold her first story. Following Clarion, she took odd jobs to support herself—even trying to establish her own laminating business, documents show; she wrote in the early morning hours before work.

But the road to success was long and slow. “In fact,” she once said, “I had five more years of rejection slips and horrible little jobs ahead of me before I sold another word.”

On display in the exhibition will be a page of motivational notes in which she writes, “I am a Bestselling Writer. I write Bestselling Books … Every day in every way I am researching and writing my award winning Bestselling Books and short stories … Every one of my books reaches and remains for two or more months at the top of the bestseller lists . . . So Be It! See To It.”

In 1975, she sold her first novel, Patternmaster, to Doubleday, quickly followed by Mind of My Mind and Survivor; the trio comprise part of her “Patternist” series, depicting the evolution of humanity into three distinct genetic groups. A review on display in the exhibition lauds Patternmaster for its especially well-constructed plot and progressive heroine, who is “a refreshing change of pace from the old days.”

And her following continued to grow.

By the late 1970s, Butler was able to make a living on her writing alone. She won her first Hugo award in 1985 for the short story “Speech Sounds,” followed by other awards, including a Locus and Nebula.

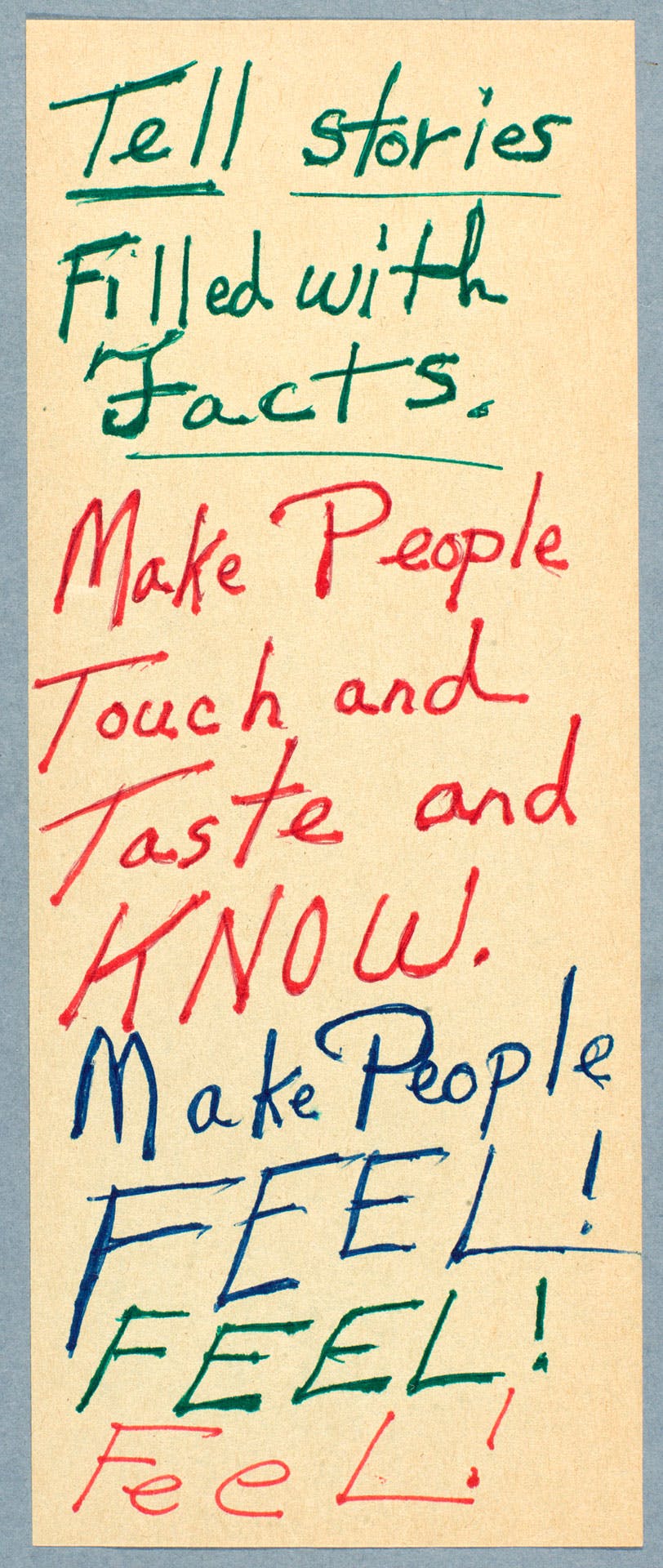

“Octavia E. Butler: Telling My Stories” will include examples of journal entries, photographs, and first editions of her books, including Kindred, arguably her best-known work. The book is less science fiction and more fantasy, involving an African-American woman who travels back in time to the horrors of plantation life in pre-Civil War Maryland. “I wanted to reach people emotionally in a way that history tends not to,” Butler said about the book. Published in 1979, Kindred continues to command widespread appeal and is regularly taught in high schools and at the university level, as well as chosen for community-wide reading programs and book clubs.

Beyond race, Butler explored tensions between the sexes and worked to develop strong female characters, a hallmark of her writing. “Being a woman in a male-dominated genre lent Butler’s stories a unique voice,” said Russell. “She would, for instance, depict women as resolving their problems through means other than violence—using flexibility, nurturing, and sensitivity instead.”

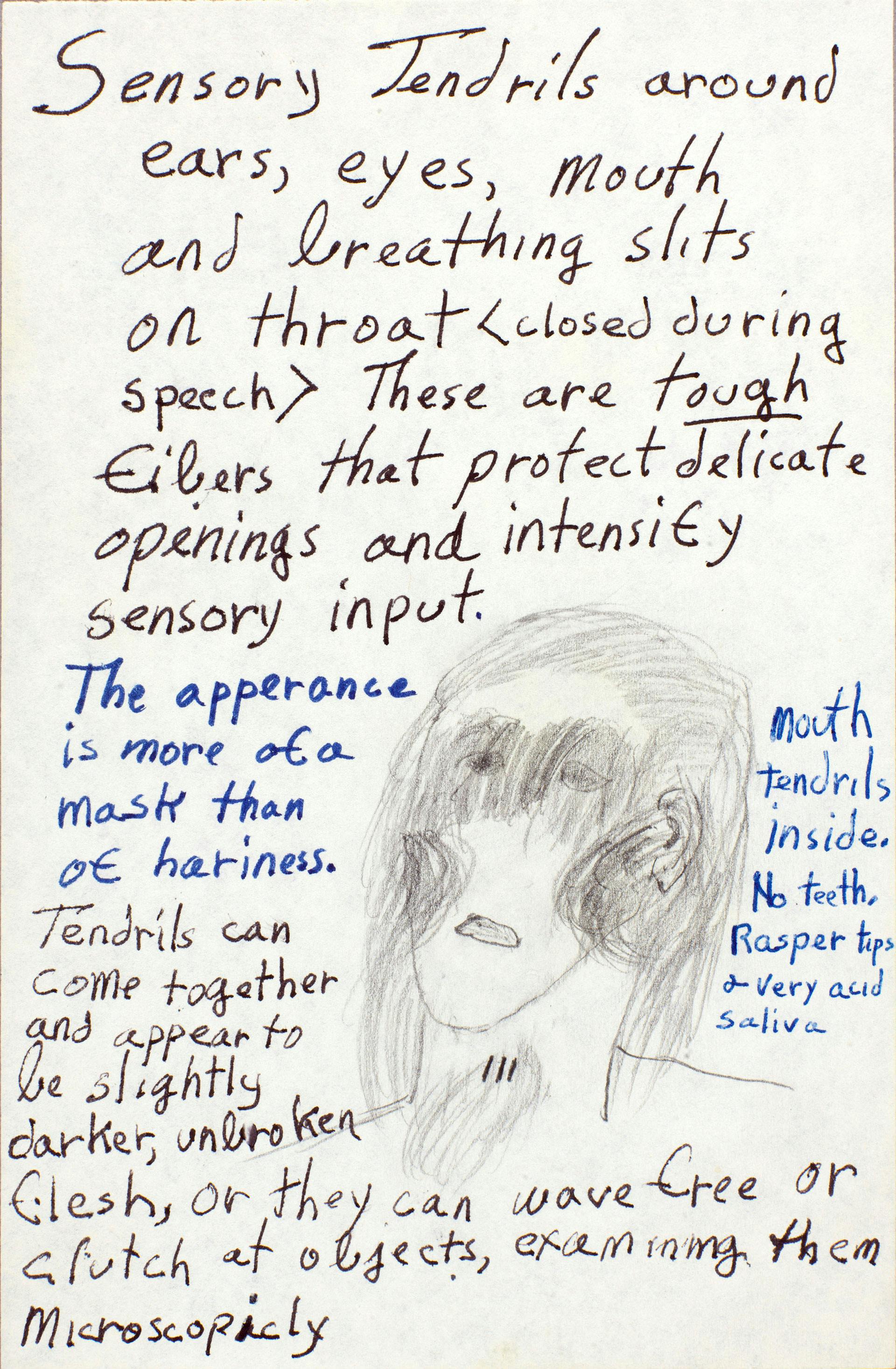

Butler once remarked, “Girls become women by giving life, and boys become men by taking it.” But she also challenged traditional gender identity, said Russell. Bloodchild, for example, is a story about a pregnant man, and in Wild Seed, the plot develops around two shape-shifting—and sex-changing—characters, Doro and Anyanwu. The exhibition includes notes Butler made about the two characters as she worked to develop them.

Butler sought to meticulously research the science in her fiction, traveling to the Amazon to get a firsthand look at extreme biological diversity in an effort to better incorporate biology, genetics, and medicine in her work. On display will be photographs from that research trip, as well as a small notebook of plant sketches. Climate change concerned her, as did politics, the pharmaceutical industry, and a variety of social issues, and as a result, she wove them all into her writing. “What’s striking,” said Russell, “is her ability to tease out and focus on issues that have had and likely will have currency for decades. She was amazingly prescient and given that, her stories resonate in very powerful ways today. Perhaps even more so than when they were first published.”

For more on the Butler exhibition, visit The Huntington website.