In our era of reality TV shows and social media, it’s refreshing to meet a guy like Joe Bark. Friendly and unassuming, the Palos Verdes resident also exudes a strength and vitality that seems to be more prevalent among folks who have saltwater coursing through their veins. And for the retired fireman, board shaper and family man, it does. Whatever the phrase “the good life” might mean to you, for Joe it’s about the simple joys of good people and a life lived in the water.

As a kid growing up in the South Bay, Joe Bark lived and breathed the ocean. His maternal grandfather—a man whose professional life included delivering Marie Callender’s pies and working as a night watchman—lived in a house on 13th Street in Manhattan Beach. That house became a gateway to Joe’s lifelong relationship with the sea.

“I started going to the beach on 13th Street, eventually going to all of the South Bay beaches and doing Junior Lifeguards, skimboarding, surfing, paddling,” says Joe. “That’s just what you did in the summer. You didn’t use sunscreen, and you came home fried.”

Joe’s father was a teacher at Mira Costa High School. His ancestors made their way to the South Bay in covered wagons by way of the Swarthout Trail. Joe’s father also coached swimming and water polo and encouraged young Joe to look up to the athletes under his tutelage—most of them young men with a passion for the water and sports.

“I liked it all,” he explains. “I was into fishing … we used to fish halibut. I used to dive—I still do—and then I joined up with a bunch of the guys from the swim team and water polo.” He shares that he body surfed with those guys too, so much so that they’d close down the beaches at night—oftentimes staying in the water until the lights came on along the avenues.

Paddleboarding, however, had yet to catch on. “I had heard about paddling,” he says, “and I started paddling with the Junior Lifeguards. It was only kinda on my radar, but I paddled from Catalina when I was 16 with a borrowed lifeguard board.”

Although the experience gave him a taste for the sport, he wouldn’t pursue it for several more years because not very many people were doing it. And for Joe, it’s the social element that he enjoys most.

Joe recalls that in his early years, the South Bay was where all of the boards (surfboards and paddleboards alike) were being built. “You had everybody—the Bings, the Jacobs, the Webers, Greg Noll—so many of the greats,” he says, “and they were all on PCH.”

Joe would take the bus or ride his bike to those shops just to window-shop, and sometimes he would even run into one of his idols. He eventually purchased his first board for $29. It was a Boyce Bullet twin-fin that was rock-hard and built out of boat materials.

But it wasn’t just the great surfers who inspired him. He shares that, in fact, the Junior Lifeguard instructors in his circle influenced him in equal measure. “I had some really good instructors who made you want to do what they did … paddle and surf. It was just a good growing up.”

Joe built his first surfboard at the age of 13 and his first paddleboard at 22. “I just did it outside, and I made a mess. I mean, I’d like to see one of those boards now … they were so bad. And I really didn’t ask for help, so it took me a long time to get started.”

Eventually though, mentors in the art of paddleboard-making did come. Among them was Eddie Talbot, founder of ET Surfboards.

“Eddie was amazing,” Joe says. “He’s one of the most fantastic people you’ll ever meet, and he got everybody into building boards because he was such a gentleman. He’d help the small guys, and to this day he’s just a fantastic person. He helped us as little punk kids, selling us resins and blanks … it was really cool.”

In the early days Joe simply pressed forward, indefatigable in practicing good, old-fashioned trial and error … both as a board maker and a businessman. “I don’t think for the first five or six years I made a penny,” he laughs.

Joe would run into friends around town or at a party who asked him to make them a board. Sometimes he even gave them away, just so he could build his crew of boarders.

“I built boards because I wanted my friends to paddle with me,” he says. “It was a passion. I’d build the boards for my friends, who would come back from mainland Mexico after sleeping in hammocks. I’d have boards for them, and they’d race. A couple of guys were really serious, but most were doing it for fun.”

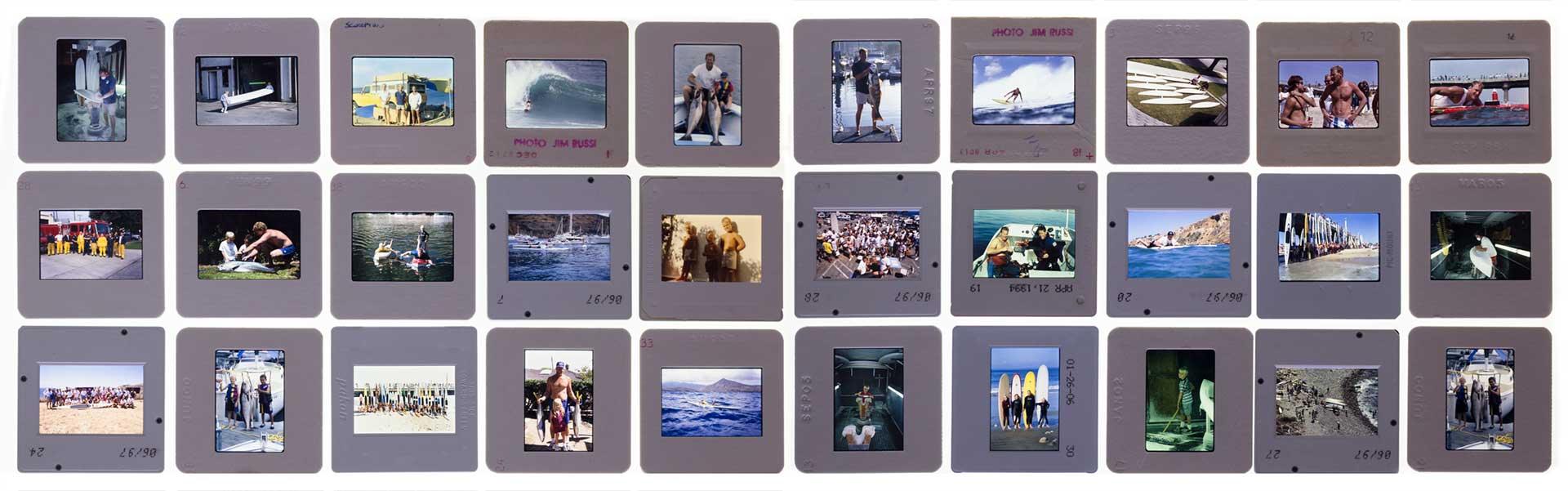

He lights up when he talks about the camaraderie and how the sport has grown. When the famed Catalina Classic Paddleboard Race was resurrected in 1982 (after having died out in the ‘60s), Joe recalls that only 11 people participated. He missed the 1982 race but joined in 1983. Today hundreds of people from all over the world join each year.

Joe recalls that in the beginning, everyone in the South Bay’s paddleboard community knew everyone else. In those “old” days, he would see a board around town and know exactly who it belonged to. But today that is simply not the case.

This is proof that others have caught on to the sport’s magic. And it’s not just the ocean that attracts paddleboarders, he says. Joe and his friends have paddled down rivers in the snow. Enthusiasts even paddle around icebergs in Canada.

Best of all, says Joe, paddling is a sport that one can “hit hard” without beating their body up in the process. He also enjoys the fact that most people can race a buddy in a workout while still comfortably holding a conversation with them the entire time.

Joe also holds dear the unique inclusiveness of the sport, which draws everyone from surfers who are recuperating from injuries to paraplegics who paddle challenging races like the Molokai 2 Oahu Paddleboard World Championships. Joe and the team at Bark Paddleboards have built boards enabling these athletes to self-rescue if they tip over. He is amazed by these paddlers.

The paddleboarding community is also profoundly philanthropic, and approximately 90% of races support a cause. Over the years Joe has played an instrumental role in organizing the Callie’s Cause event—a paddling and running hybrid event near Palos Verdes with a mission to support epilepsy research. The Ocean of Hope race raises funds to support those who are affected by cancer. The Adler Paddler—in honor of paddler Steve Adler who died from a genetic thoracic aortic dissection—supports research into aortic health.

On average, there are 20 to 25 local racing events held each year; sometimes multiple events are held in a weekend. Participation in such races is free, but participants donate money to help selected organizations meet their fundraising goals.

Joe has always enjoyed working with his hands but is quick to point out that functionality is his paramount concern. “I’m concentrating on creating state of the art race boards rather than the wooden inlay wall hanger boards that others are making.” But he appreciates watching other craftsmen lend artistic flair to their own work.

For many years, Joe hand-shaped all of his boards himself, which in the beginning he only built for his friends in the paddleboarding and surfing communities. But today he has a team of computer-proficient board builders who can take a master board that he has built, scan it and then reproduce it … perfectly and repeatedly.

Joe describes the scanning process: “It basically gets your blank almost exact. You can take your magic board that’s proven and give it to the guy, and he will scan it and duplicate your same board—the same rocker or concave or v-rail or whatever—and then you finish it. There’s enough leeway to change things. I can soften a rail, harden a rail, thicken or thin the board or turn a 9-footer into a 9-6.”

The excellence of Bark boards is recognized the world over and has been embraced by some of the biggest names in the sport.

When asked what kinds of boards are most popular, Joe says that the stand-up board is stronger than ever. At the Chattajack race in Tennessee, a one-day, 32-mile race down the Chattanooga River, for example, fans of stand-up racing will drive for 15 hours to get to the event. But again, it’s the social element of the sport that Joe returns to when talking about the stand-up style.

He describes these events as being like family reunions. And his team at Chattajack, though it used to consist of older members, now even includes kids who are Junior Lifeguards, as well as college swimmers and water polo players. The younger members will jump on a board and are at the top of their game almost overnight.

“It’s the only sport I know,” Joe shares, “where it’s ‘the more the merrier.’” Whereas other competitive sports entail players getting benched or rotated out of a game, even competitive paddling gives participants an experience of being supported. Paddlers may initially feel intimidated when they join a group, Joe says, but then within in a few days they are “locked in with everybody, and the best paddler is willing to teach the brand new person everything he or she knows, coach the new player and help him or her get through it.”

Regardless of skill level, though, all are united in the road trip spirit that makes participating in such races so fun. Joe loves everything about these races—from loading up the car on the way there to falling asleep the night after a race, muscle aches and all.

Joe’s entire family—wife Aimee, daughters Gemma and Emily, and sons Jack and Sam—loves the water. Jack and Sam, ages 23 and 19 respectively, have joined Joe in board-making. “It’s awesome,” says Joe.

He shares that even as kids, Jack and Sam would join him in the shop. As they got older, they began pursuing it as a hobby. Before Joe knew it, they were helping him clean and router his boards. Joe proudly shares that friends have even begun requesting Jack’s work.

For 27 years Joe served Redondo Beach as a firefighter. The final six years of that career he spent on a harbor patrol boat. So how does this lifelong waterman look back on his career fighting fires?

“It was a great 27 years,” says Joe. “I walked out the door with no injuries and worked with a great group of people. This was a wonderful career for me.” It was rough going at times, however, giving 110% to both his career as a firefighter and Bark Paddleboards. Oftentimes Joe had to pull all-nighters just to keep up with production.

It worked out well for him that he has always been naturally “wired” and never one to waste time. He would sometimes build boards even when he didn’t have orders, simply because he loved the sport and wanted to see more paddlers on the water.

He retired four years ago at the age of 53 and now enjoys the freedom his schedule allows him. Not unlike a kid who just wants to play with his friends, he says it frustrates him when work makes demands on others’ schedules. They’re a spontaneous bunch though, Joe Bark’s circle, and they make getting out on the water together a regular priority.

Now that his schedule is more flexible, seizing the day is more important to Joe than ever before. Prior to his retirement, the demands of his work required his missing a lot of good days out on the water. Not anymore.

Now Joe will head to the shop at 4 a.m. so that by 8 or 9 a.m., he’s ready to go paddleboarding, surfing, fishing or diving. “I used to miss races on weekends,” he says, “but you don’t get those days back. If something is happening, I don’t want to miss out on it.”

Joe says that the most rewarding experiences of his life so far have been marrying his wife, Aimee, having kids and watching them have fun on the water—not because they’ve been raised to but because they want to. Joe fully realizes that his kids might very well have wanted nothing to do with the water. As is the case with his friends, however, it frustrates him when the demands of school or jobs make it difficult for his kids to match his spontaneity when the water is good.

In raising their kids, Joe and Aimee were the perfect yin and yang, with Aimee guiding the kids’ academic lives and Joe instilling in them a readiness for adventure. Joe recalls occasions when Aimee would be out of town, and Joe would take the kids to the beach … even on school days.

Joe and Aimee homeschooled their kids for several years, which enabled them to have experiences they might otherwise not have had on a more traditional schedule. Joe recalls getting a midnight call from his friends telling him that the sea bass were biting in 60 feet of water off Rocky Point, and then waking Jack up so they could head into the foggy night together and join the action.

Is life a marathon or a sprint? When asked this question, Joe pauses before divulging that while a lot of his colleagues will read the blueprints and “do it right the first time,” he prefers to dive right into his work. The ensuing mistakes sometimes make the road a bit longer, but Joe’s process is part and parcel of his high energy level and his adventuresome spirit.

He’s gotten smarter though, he says, because he simply can’t afford to make as many mistakes anymore. But life remains a marathon for him nonetheless, because he’s not all that interested in going anywhere fast.

“I plan to shape (boards) forever,” Joe says. “Even if I won the lottery, I’d still shape for sure.”

For Joe, passion is spending time with friends and family and sharing great experiences. This is his raison d’être.

And more to the point, Joe confesses it pains him to only tell a friend or family member how good the fishing was or how great the conditions were out on the water. At the end of the day, Joe Bark’s passion is building and racing boards … and engaging in those activities with the people he holds dear.

“I’ve always had fun with my work, even when I had jobs as a kid,” Joe says. “I can’t imagine doing a job I didn’t like. I see guys out there doing stuff I couldn’t do and wouldn’t want to do. I’d rather dig ditches than sell door-to-door or drive the freeways—that would kill me.”

Joe Bark has worked in construction, as a firefighter, painting and roofing … and of course building boards. And he says that his days have generally been bookended with getting breakfast somewhere before work and then finishing the day by getting in the water, whenever possible.

Perhaps it’s that love for his work that has enabled Joe to grow Bark Paddleboards from a one-man outfit to a premier purveyor of boards. In the years since he founded his company, more than 200 paddleboard companies have emerged around the world, though prone paddleboard companies have not really showed up.

All of Joe’s boards are made custom and also produced under the Bark name manufactured by Surftech. Bark Paddleboards also has a team of ambassador paddlers who help spread awareness of the Bark brand.

Joe does not necessarily consider himself a product of his environment. “I’ve got my own ideas, and I don’t fall into things. I’m always trying to talk my friends into doing it my way,” he laughs, “and I’m pretty stubborn in doing it my way, even if it’s wrong.”

And yet, you’ll recall, it was his father’s directive to emulate the fine examples of the athletes he coached that played a part in shaping Joe’s course in life. That, and the bountiful, rich, textured geography of the South Bay itself.

In fact it’s when talking about the South Bay that Joe—a normally low-key communicator—approaches his version of gushing. “It’s got everything you need—paddling, fishing, diving, volleyball and boating, wonderful beaches,” he affirms. “It’s amazing … hard to beat.”

He offers that friends from other areas come here for the races and are blown away by such experiences as hiking on the fire roads, and by how on a clear day you can be out fishing on the water and still see snow on the mountains in the distance.

The South Bay’s abundant wildlife has also impacted Joe in a big way. He describes the experience of paddling among whales, porpoises and seals in almost spiritual terms. He shares that whether he’s following a whale or looking down at kelp beds and fish or checking the diving conditions for later in the day, paddling out on the water has the power to clear his head in a way that’s effortless and intrinsic to his being.

Once, when he was diving not 200 feet off the Redondo Pier in Red Canyon, Joe was suddenly startled to find that the water had gone completely dark. With a racing heart, his immediate thought was that perhaps he was in the presence of a great white shark. It was not a shark blocking the sun, however, but a young grey whale. Its face was mere feet from Joe’s, and the animal silently stared at him for several minutes.

Moments later, the whale’s mother swam overhead, forcing Joe and his diving partner to find a way to quickly surface so she would not inadvertently crush them. As exhilarating and alarming as the experience was in the moment, Joe cites the story as an example of how the wildlife in the South Bay has graced his life.

Ask Joe if he’s ever had a profound moment of uncertainty in building his business, fighting a fire or being on the water, and he’ll likely respond with a shrug. He’s quick to downplay his challenges and instead prefers to highlight the fact that although every day presents its struggles, his own loads have been lightened by the wonderful and supportive people he’s chosen to spend time with.

“I surround myself with the greatest paddlers.” These individuals get out and win races, Joe says, and although he does not, building the boards they all race on gives him enough satisfaction. He credits his friends with encouraging him to train even when it is windy and cold, which perhaps is a metaphor for how this somewhat private man has handled the difficulties in his life.

“I hope I’m still paddling in 20 years,” he says. “It’s a long time from now, but there are guys in their 90s racing. Not far and fast, but they enjoy it.”

Joe Bark hopes to paddle and shape boards until his dying day—and also hopes he still has a team to share the ride with. “People don’t know that we’re a small company. We use the best glassers in the business. It’s just me, Jack and my wife, but we have a lot of friends. I hope I’m around for 30 years.”