Redondo Beach’s The Bel-Airs didn’t know what was coming either. The young South Bay band became popular around this time and kept themselves busy playing the Redondo Elks Club, the Portuguese Bend Club and the Torrance Grand.

In 1961 band members Paul Johnson (at all of 15 years old) and Richard Delvy wrote a song together: the immediately captivating “Mr. Moto.” The band recorded and released the single that summer. Disc jockey and radio personality Sam Riddle was the first to play it on Los Angeles radio KRLA, and it fast became a major regional hit—nearing the Top 10.

Paul says he was in the right place at the right time as “Mr. Moto”—along with Dick Dale’s “Let’s Go Trippin’”—were destined to become the two songs best believed to have ignited the era of surf music.

The musical sound of The Bel-Airs and Dick Dale was adopted into the new style as soon as it began. They were there before, during and after it all happened, as were some of the other bands that had started before the term “surf music” was ever coined but were nevertheless part of its bloom.

Everything fell perfectly into place, partly through coincidence and partly by design. The Bel-Airs’ sound fit into and belonged to the genre seamlessly as it appeared. And the surfers were digging it.

The emergence of surf music came at a time when Southern California had already become well-known for its gorgeous weather, endless shorelines, magnificent sunsets and, of course, surfing. Society’s teenage domination had sprung, and the beach scene was just another outgrowth—albeit a profound one.

The new music and this new subculture reflected on and legitimized the original surfing community, leaving them more than happy to think they started it all. If the beach was a cool getaway, the surfing community was a defined lifestyle. Besides the incredible music, the scene had its own art, fashion, hairstyles, language and attitude—all happening at the same brief, mysterious, phenomenally stoked time.

The South Bay was one of several concentrated focal points during this period, and at one point surf music itself was labeled “the sound of the South Bay.” Sadly, it didn’t stick.

Live surf bands were known to be insanely loud—the guitars plugged in and cranked up, up as far as up went, reaching an unprecedented level by either night’s end or when the cops showed up. It had to be loud or how else could you drown in it? The volume attempted, among other things, to mirror the release a surfer felt, the abandon and risk of being alone on your own wave, shredding through the world.

As the amplifiers blew up and caught on fire, bigger and more powerful models were designed to make things even louder. There was never need to worry about being able to hear the singer over the instruments, as vocalists in surf bands were (mostly) done without—it was about guitars, bass and drums.

The loudest of them all (notwithstanding Dick Dale’s thunder in Balboa) was Eddie & the Showmen. Hailing from Palos Verdes, ex-Bel-Air Eddie Bertrand and his band released several records, including “Mr. Rebel” and “Squad Car.”

Named after Fender’s Dual Showman amplifier, they’d better have been loud. Eddie’s exploratory use of a reverb unit—with its auditorium-like echo further trying to expand the “wet, liquid sound” experienced while surfing—resulted in an urgent, tough sound forever associated with surf music.

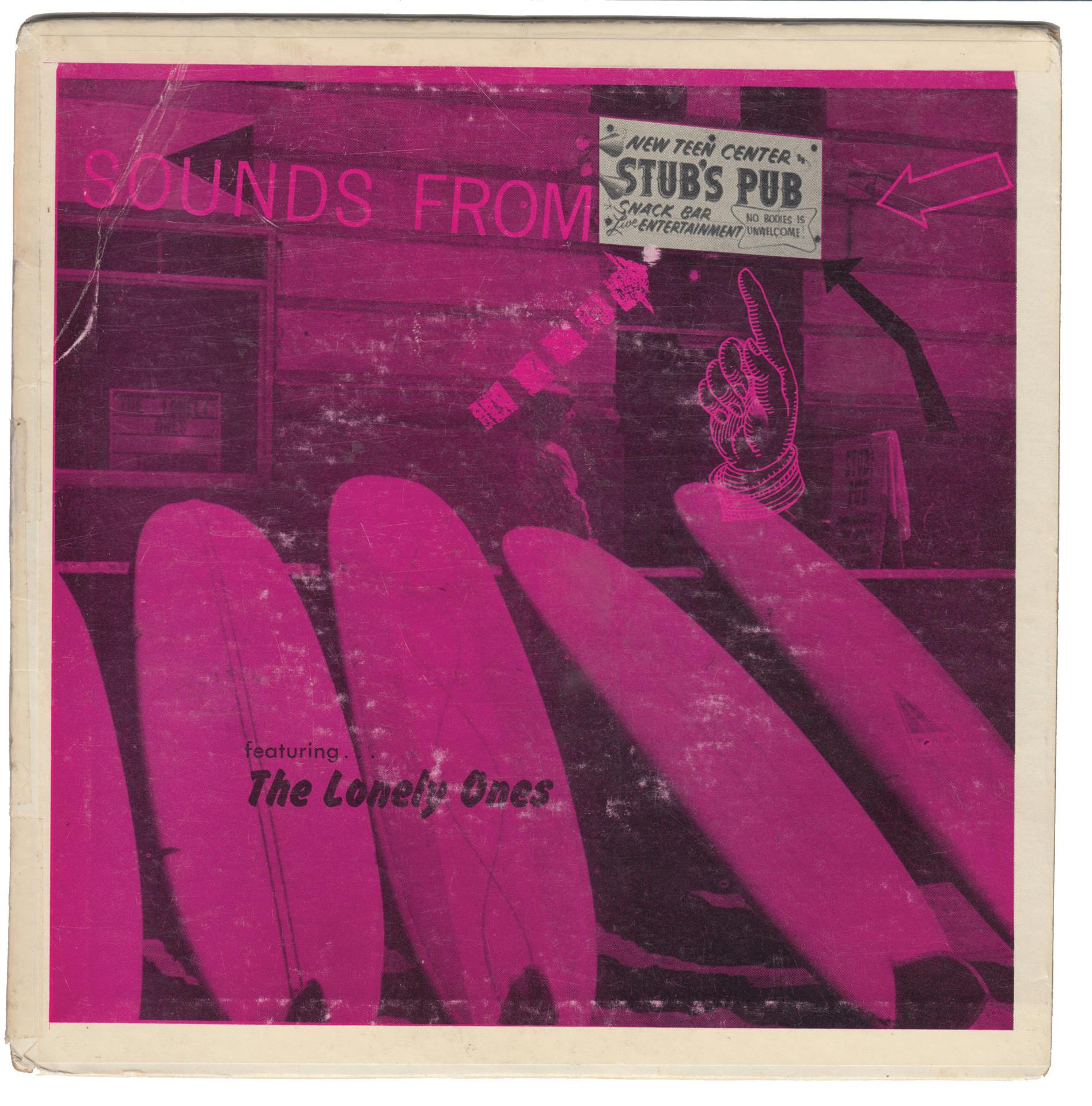

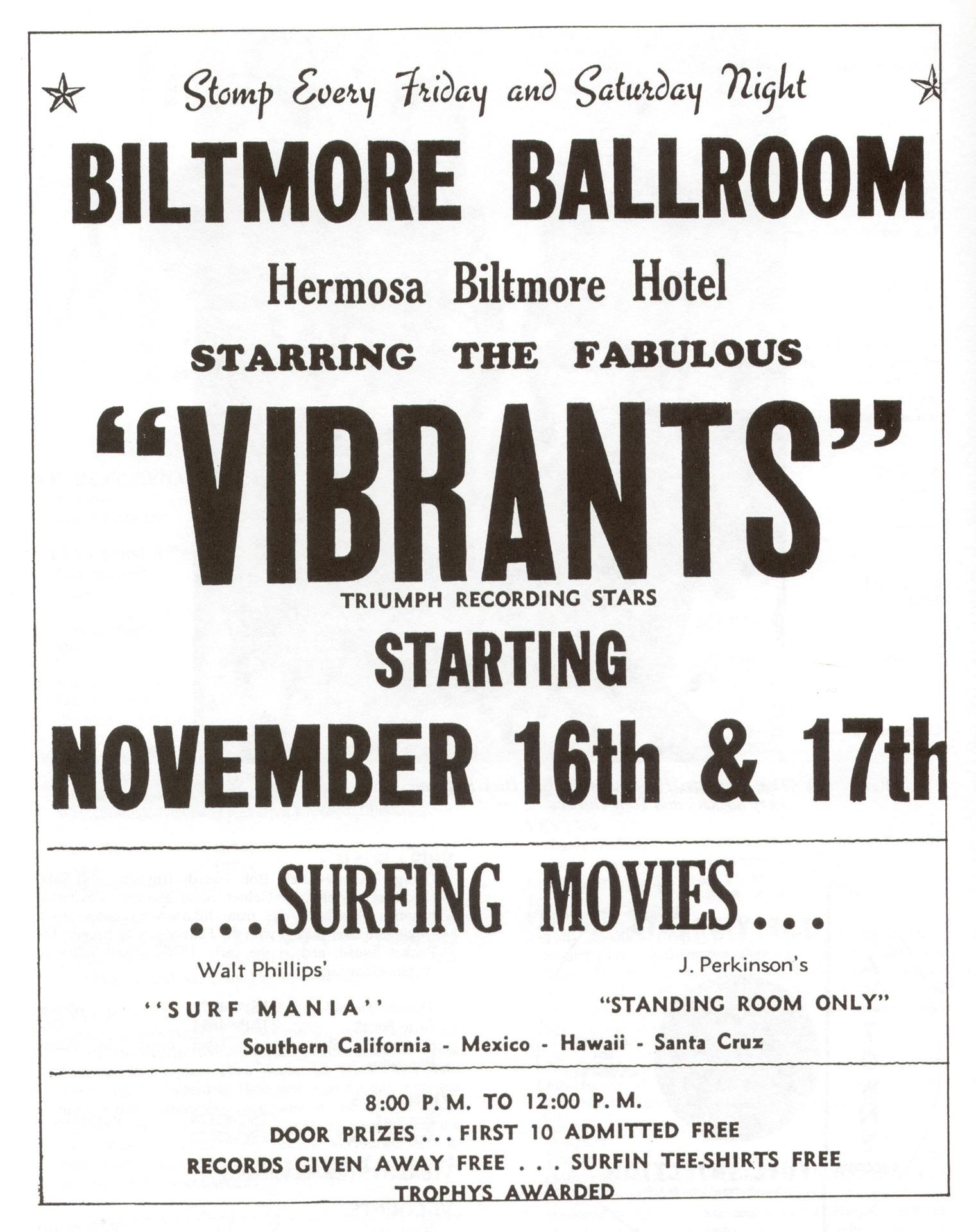

Another significant South Bay band was The Challengers. Their 1962 Surf Beat album was the first nationally distributed LP to consist entirely of surf music. Two popular surf bands from Manhattan Beach were The Revelairs and The Vibrants (including guitarist Tony Guidice). Also of great note are The Baymen, Thom Starr & The Galaxies, The Journeymen and The Lonely Ones.

The Crossfires from Westchester played at the Revelaire Club and Torrance Recreation Center’s auditorium. Known for their humor, onstage antics and not-one-but-two saxophonists, they were filling every hall and club they played. Doomed for success as The Turtles, they moved to the Sunset Strip when surf was up.

Let us not forget The Beach Boys (yes, them) from Hawthorne. Though tightly associated with the surf scene and surf music because of early-‘60s hit singles like “Surfin,’” “Surfin’ Safari” and “Surfer Girl,” their music was seen more as surf songs than surf music by many of the original bands and fans. The immense popularity they brought to the sport of surfing began crowding the beaches and bugging the locals.

Dennis Wilson, the group’s drummer, would skip class at Hawthorne High and drive to Torrance Beach to surf and hang out. He absorbed the different world that was happening there and relayed what he’d discovered to Brian, his older brother, who thrived on the stuff. Brian’s interpretations of his brother’s adventures would lead to some of the most beautiful and enduring music of our time, and he would go on to become one of the most highly respected composers of the 20th century, outgrowing surf music by miles.

The Beach Boys stayed involved within their community after reaching nationwide success and continued performing locally alongside the other bands as long as they could. Brian would attend The Bel-Airs concerts and made it known he was a fan. The Beach Boys performed at the grand opening of Torrance’s Wallichs Music City on November 15, 1963—a generous gesture for them at that point in their career.

Sadly, the house that Brian, Carl and Dennis grew up in at 3701 West 119th Street is now part of the 105 freeway.

Once The Bel-Airs hit the charts with “Mr. Moto,” they needed a larger hall in which to perform as their fan base continued to grow. Soon they were the house band at the newly opened Bel Air Club on Catalina Avenue in Redondo Beach—named in the band’s honor and better equipped to hold their large audiences.

So-called teen centers like the Bel Air were springing up along the coast and offered a much-cherished escape for young people at the time. The allure of the stomps was divided between hearing the live bands, dancing and meeting friends with sand on your feet.

It was the music, though, that fascinated its audience most and brought attendance at the clubs to new levels. These live performances, along with the increasing popularity in the sport itself, helped create a shared, positive and energetic climate that spread quickly.

Longtime locals welcomed like-minded fans until they were sniffed out as weekend surfers and party crashers. A minor dance craze called the Stomp was fun, but not enough to keep everyone from Twisting.

The Bel Air Club was renamed the Revelaire Club by new owner and popular radio DJ Reb Foster in 1963 and turned private with an age limit of 14 to 21. The Revelaire continued hosting the most popular stomps in the area for nearly two years, with Eddie & the Showmen appearing often.

The Knights of Columbus Hall in Manhattan Beach and the Torrance Rollerdrome often held stomps so overcrowded there was no room to dance. No matter, you could always listen to the bands and talk (make that shout) to whomever you were rubbing shoulders with.

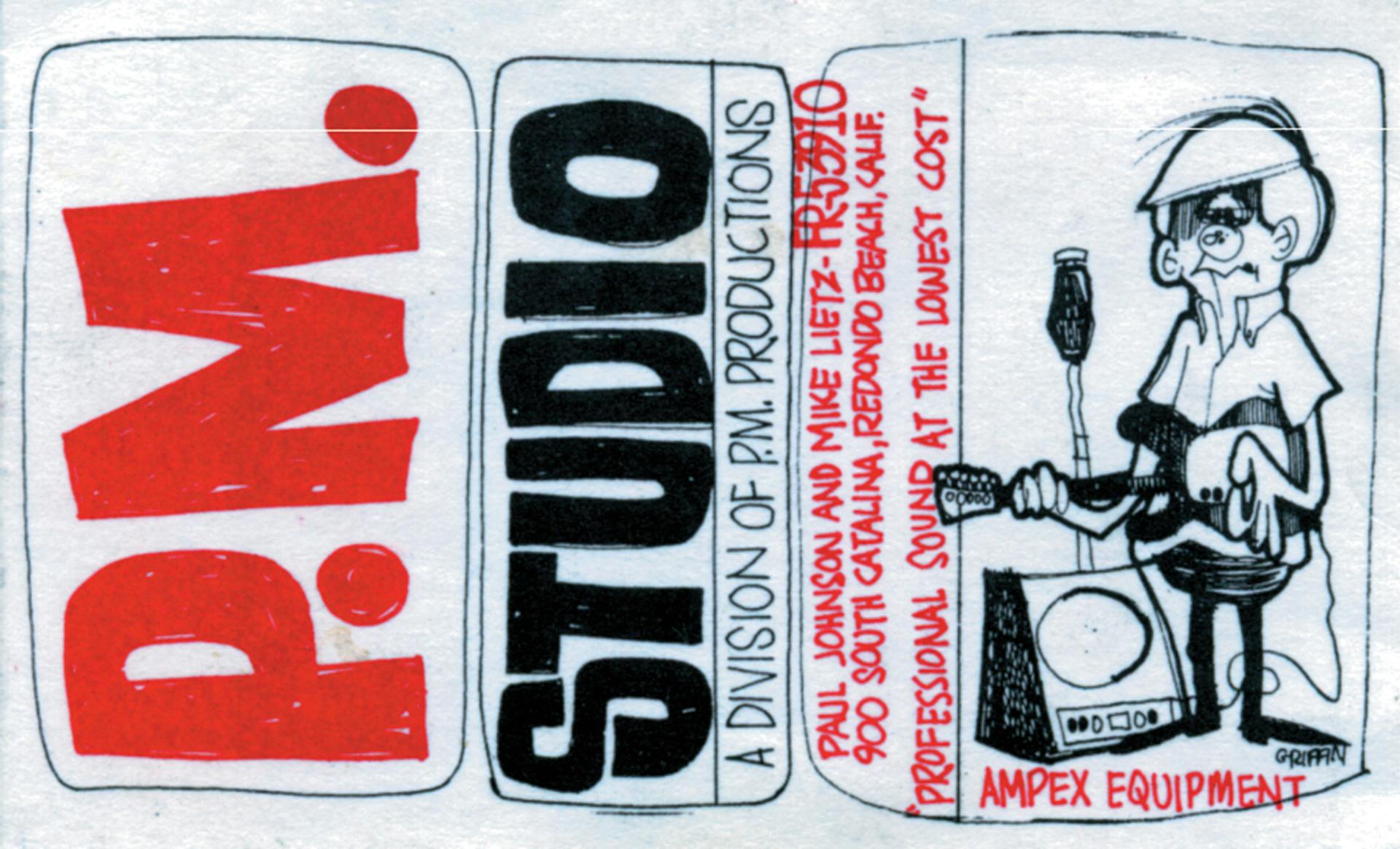

The Hermosa Biltmore hosted some major surf concerts and dances in ’62 and ’63—during one of the building’s many transformations. Its biggest show attracted more than 1,500 fans. For a brief time a surf dance club called Stub’s Hub operated in the Hermosa Biltmore’s old cocktail lounge with The Lonely Ones as house band.

The scene began to wane in the fall of ’63. Autumn has a way of doing that. The arrival of what’s-their-names from across the Pond early the next year was the final nail.

Things deteriorated further with Hollywood’s inane beach-party movies, contrived groups like the Sunrays and Madison Avenue’s inevitable overexposure. Many bands kept on playing and some never gave up, but sadly the original surf scene was essentially over.

A significant revival took place in the late-‘70s, alongside and cooperatively with punk. By the mid-‘80s a full-on surf reawakening had happened. Today, according to noted music historian John Blair, a new scene is thriving—with thousands of bands currently performing globally. He sees the universal language of surf music playing and living on.

By the way, if any of you have an original copy of “Wipe Out” on the DFS label, take good care of it. A copy recently traded hands for $2,500.